When the Center for Biological Diversity proposed that the Orange Clownfish, Amphiprion percula, was endangered, I found myself saying “No way…it is arked!”

Genetics | Hybrids | Species Part 1| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6a | 6b | 6c | 6d | 6e | 7 | 8 | Index

The Role of Captive Propagation in Clownfish Preservation

Another look at the Aquarium Ark in the context of preserving the natural biogeographic diveristy of Anemonefishes

by Matt Pedersen

This is the point in the story where it all comes together. Genetics and Hybrids were covered fully in the September / October 2014 issue of CORAL Magazine; we kicked off species diversity in the November/December 2014 issue, and expanded on that familiar basis online.

The result is a tremendous and unparalleled documentation of natural biogeographic diversity which surpasses the general taxonomic understanding of Anemonefishes. Knowledge is power, and with great power comes great responsibility. The vast and deeper understanding of clownfish diversity means nothing if we simply ignore it.

By virtue of simply being aquarists, we have yet another power: to promote and perpetuate the natural biodiversity which exists in the world. Often times, this occurs unintentionally, while other times it is the dedicated aquarist making a conscious effort to bring a conservation ethic directly into their daily aquaristic pursuits.

The Misunderstandings of the Aquarium Ark

First, I must take you on a tangential journey to examine some history, before coming to the concrete lesson and suggestions which wrap up this series.

Viewpoint: The Aquarium Ark by Matt Pedersen – CORAL Magazine, May/June 2012

I’ve raised the topic of the Aquarium Ark, first in a completely humorous, tongue-in-cheek online article, but then in a serious and measured fashion in CORAL Magazine’s May/June 2012 issue, as well as at MACNA 2012. To my surprise, the concepts I presented were met with consternation and apprehension within some portions of the marine aquarium community, particularly from very knowledgeable aquarists who I think failed to see the forest for the trees (though they might say the same about my viewpoint).

I believe freshwater aquarists and the scientists connected with that interest group have a better grasp on this invisible force that exists within the aquarium hobby and trade (the same talk I gave at MACNA has been met with high praise among veteran freshwater aquarists). The reason they don’t object, the reason they understand it, is simply that our freshwater-keeping counterparts have the benefit, and wisdom, of experience. By comparison, I might argue that the marine aquarium hobby, but particularly that of breeding fish and invertebrates, is only in its teenage years at best!

The Aquarium Ark concept is not perfect because it is not orchestrated; it is simply a by-product of everyone doing what they love, spending our disposable income in aquatic pursuits that require, among other things, livestock. In short, we wind up creating back-up captive populations of species simply because we like putting them in our tanks.

That said, die-hard enthusiasts often wind up maintaining the tiny, obscure, nondescript, troubled species that the rest of the world would be indifferent towards. We’re talking about the kind of species that no one would donate to save, that governments would gladly extirpate to build the latest resort complex. These are the species for which everyone who cares about them would probably fit around my dining table…maybe spilling over into my living room. This is, to me, the ultimate example of the Aquarium Ark.

Reintroduction—The Red Herring

When talking about the Aquarium Ark, the topic of reintroduction often comes up. I can only surmise it is because of the biblical connotations surrounding the term “ark,” even though the actual definition of “ark” is hardly the story of Noah.

Reintroduction is perhaps the ultimate red herring and strawman. In an ironic twist, my 2012 article never so much as implied, let alone explicitly stated, that we could or should reintroduce endangered or extinct species from, say, the tanks of a basement hobbyist; and yet reintroduction is always brought up in an effort to challenge and discredit my observations. I’m still willing to discuss the notion of reintroduction when it is raised, not because that’s what I’m promoting, but because it represents a possible outcome of a successful Aquarium Ark!

Perhaps most interesting to me is that, since we know what the obstacles to reintroduction are, why aren’t concerned aquarists and scientists proposing solutions to the “problems” so that the massive conservation resource and repository that exists in the commercial aquarium trade can be that much better?

Meanwhile, one thing is very true: we will never be able to reintroduce a species if we never bothered to preserve it in the first place. When it comes to our coral reefs, we may never be able to reintroduce, say, a rare clownfish species or variant—even if we have the fish—if the reefs are no longer able to support them. And yet, for all the viewpoints and opinions that suggest this is foolish or hopeless, we already have documented scientific studies demonstrating the successful reintroduction of captive-bred Amphiprion bicinctus into the Red Sea. Hmm.

The Aquarium Ark Posterchild

Despite all the criticism being levied about the aquarium trade and hobby’s ability to preserve a species, we need only look to my poster child for the Aquarium Ark, Epalzeorhynchos bicolor, the Red-tailed Black Shark. This species persists almost solely due to captive cultivation for the ornamental fish trade, and was thought, for years, to be extinct in the wild.

![The posterchild of the aquarium industry's Aquarium Ark in action - the Red-tailed Black Shark, exists only due to aquarists. By Pseudogastromyzon (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.coralmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Red-tailed_black_shark_1000w.jpg)

The posterchild of the aquarium industry’s Aquarium Ark in action – the Red-tailed Black Shark, exists only due to aquarists. By Pseudogastromyzon (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The discovery of a single specimen in the wild in 2014 was cause for massive celebration, and yet I can go to my local fish store and see half a dozen swimming in their tanks any day of the week. The wholesale price could even be considered offensive by some, considering you could buy a few critically endangered Red-tailed Black Sharks for the price of your average fast food combo meal. It would seem that our supply of “critically endangered” Red-tailed Black Sharks is simply never going to run out. Why?

The relevant point is this: we know this species because of the aquarium trade. We value this species because of the aquarium trade. This species, which was thought extinct in the wild for 15 years, persists in great numbers in captivity, solely because of the aquarium trade.

And more specifically, the Red Tailed Shark exists solely because the public thinks it’s a pretty fish and would like to have it in their tanks!

Scientists, academics, and environmental managers will argue over the merits of whether this captive population of Red-tailed Black Sharks could ever be used to restore the species to the wild. (I have a hunch that their concerns are vastly overblown, given the routine regularity with which we throw endless amounts of captive-bred game fishes into freshwater and saltwater around our own country.) Without the aquarium trade (and the Aquarium Ark this commercial consumption created), we wouldn’t even be able to have the conversation.

Might the Red-tailed Black Shark forever be a “zoo species” (one which will only persist in captivity)? Perhaps, but to me this is better than not having the species at all. The survival of the Red-tailed Black Shark in captivity, solely as a function of the commercial aquarium trade, serves as a reminder of past mistakes and hopefully can prevent future ones. Perhaps the biggest mistake we should avoid is deciding that the aquarium trade cannot serve a useful purpose in the conservation of a species.

The “Ark” As It Pertains To Clownfishes

When it comes to clownfishes, the truth is that they are potentially under threat. While the aquarium trade does get blamed at times for possible overharvest, the reality is that if the trade in wild clownfishes ended today, it would do nothing to change the environmental damage that has already occurred, and that which is predicted to occur.

Still, the aquarium industry could probably rely on captive cultivation for almost all our clownfish needs these days. I’m not here to downplay the potential benefits that sustainably-managed wild fishery could bring, but I will say that breeders are the ones who really have a justifiable need for wild fish. The average aquarist is probably better served by captive-produced clownfish when available, as wild clowns remain more problematic than their captive-bred counterparts. Frankly, I’ve long believed that our time is finite when it comes to having access to wild reef fishes regardless…the environment and politics would suggest that reality at some point in the future. Therefore, now is the time to make sure we build a solid captive-breeding base for the future of our hobby and industry.

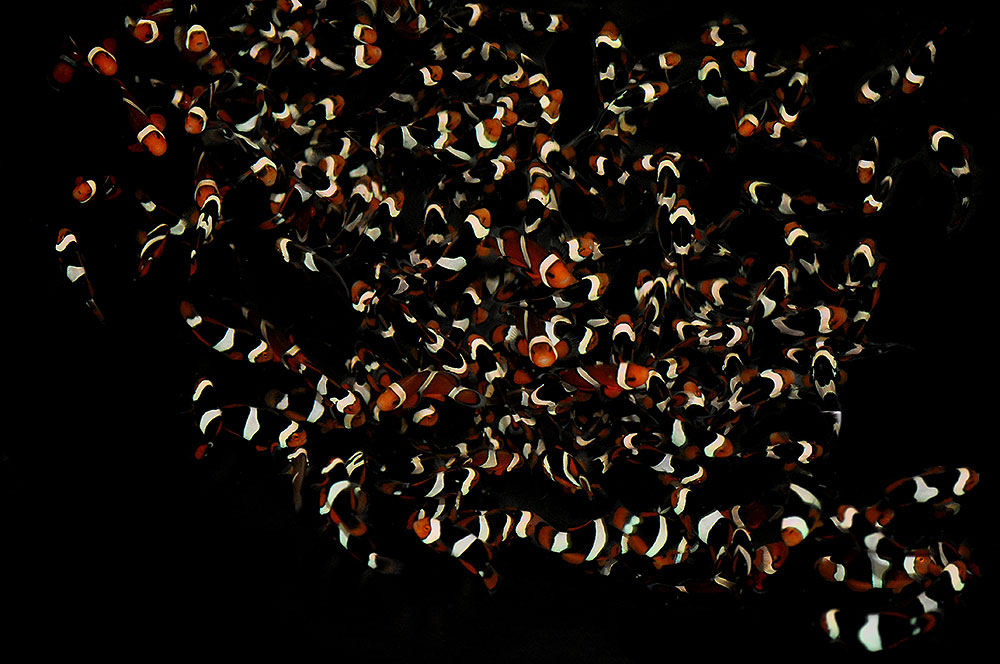

I remain worried on some levels that rampant, careless breeding of “designer” clownfishes can and will displace the natural forms in cultivation. The designer clownfish are luring new aquarists to the pasttime of breeding clownfish in droves. These aquarists have dollar signs in their eyes, and they are effectively turning the Ocellaris/Percula species complex into what is truly the Guppy of the Marine Aquarium World. The fish themselves are almost becoming the equivalent of living baseball cards: collectors items to be enjoyed, bred with, re-paired at whim, traded, and sold, always looking to one-up some other new breeder or to enhance standing in the breeding community. Broodstock—more than being treated as a foundation of good breeding—is viewed a trophy which can be bought if you have enough disposable income. Such breeders rarely have any understanding of the long-term ramifications of their choices, making it ever more important to reconsider our designer foundation stock from the ground up, if we hope to see something better come out of our novice breeder-collectors.

Meanwhile, with a fish like the Mccullochi (Amphiprion mccullochi, often simply Mcc), we had one entry into the hobby and industry for that species; if it is pushed out now because everyone prefers and buys Picasso Perculas and Domino Midnight Ocellaris, that is an opportunity lost. Should it come to pass that Lord Howe’s anemone population is lost due to bleaching, we would see the disappearance of the Mccullochi from the wild. And if we don’t have the Mccullochi in cultivation because consumer purchases didn’t support the effort and clownfish collectors are busy swapping Designer Perculas for specimens with an extra 2% white coverage, Mccullochi Clownfish will be fully extinct and not just “extinct in the wild”.

Unfortunately, designer clownfishes are meeting a demand for the unusual and rare. Outwardly, this demand apparently cannot be met by the natural biodiversity of clownfishes in the ocean. However, I believe that most aquarists have no comprehension of the immense natural diversity of clownfish in the wild. We see a list of 30 species, and it ends there. We couldn’t be more naïve.

This lack of understanding is something that the aquarium media, and science itself, has perpetuated. We’ve been told there’s nothing special beyond 30 species. We don’t appreciate these natural species and variants because we don’t know them; there isn’t a prominent reef blog or braggadocious breeder touting his must-have Amphiprion clarkii from Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia, sparking fierce criticism from a fellow breeder producing the “inferior” Yellow-faced Black Clarkii from Mandang, PNG!

The “Australian Black Clarkii” being produced by multiple commercial breeders now – this one courtesy Sustainable Aquatics

This lack of understanding could be the cause of the hobbyists’ chronic need to obsess over whether a fish has a “helmet” or a “muttonchop” while failing to appreciate that there could be 11 natural types of Amphprion clarkii, every one more remarkable and beautiful on their own merits. Yet, if a breeder had concocted these varieties of A. clarkii in his basement fishroom, he’d be called a genius!

This is the fundamental reason I embarked on this article series: to open our collective minds and hearts to the natural splendor that already exists in our oceans, and perhaps to cure our hobby of this malaise before we are only left with captive-bred mutts while the good stuff is off limits or extinct.

The Pupfish Dichotomy

As I close out this segment, I’ll insert a timely observation that would never have made it into print, because it hadn’t happened yet. Jason Bittel, writing on OnEarth.com on October 29th, 2014, posed the question, “Should We Really Save The Desert Hole Pupfish?” In his article, he notes that the US FWS invested 4.5 million dollars in the Ash Meadows Desert Fish Conservation Facility—in short, in 2013 alone, the US government threw at minimum 4.5 million dollars towards saving what is now a species comprised of roughly 100 fish.

The highly endangered Devils Hole Pupfish – Photo credit: Olin Feuerbacher, USFWS | CC BY 2.0

Bittel’s article drew a very surprising mix of pro & con commentary on the AMAZONAS Facebook page from aquarists, who, admittedly, I thought would be more uniform in their leanings. But I truly believe that if the Desert Hole Pupfish had been a popular fish in the aquarium trade, it would share a fate more like that of the Red-tailed Black Shark, and the US government probably wouldn’t be dumping untold millions into that species along the way. (Yes, this is a vast oversimplification of the Pupfish predicament. It’s a rhetorical example only.)

If we all take a big step back and examine the positive impact our pastime of private aquarium keeping can have when pursued in a conscientious and informed manner, then we might never be talking about governments throwing hundreds of millions in tax revenues towards oh, say, saving clownfishes. We’ll take care of our own, out of our own pockets, doing it because we love it. The question of money, and the question of whether we should be doing it in the first place, won’t even enter the equation.

That’s how the Aquarium Ark comes about. If we can acknowledge this unorchestrated and hidden force, then we might realize the more important and overlooked role that captive propagation for the aquarium trade plays in preserving biodiversity, and why it is fundamentally unmatched by any actual coordinated effort. When we can recognize that force for what it is, then we can harness it, and suddenly we enter a whole new way of looking at the aquarium trade.

Continue to the last section; Changing Our Clownfish Mindset

Genetics | Hybrids | Species Part 1| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6a | 6b | 6c | 6d | 6e | 7 | 8 | Index

References:

Viewpoint: The Aquarium Ark, by Matt Pedersen. CORAL Magazine, May/June, 2012. Page 34

Nearly Extinct Red Tailed Shark Isn’t Gone Yet, by Matt Pedersen. August 4th, 2014 – http://www.reef2rainforest.com/2014/08/04/nearly-extinct-red-tailed-shark-isnt-gone-yet/

WE are NOAH’S ARK – The immorality of aquariums, debunked, by Matt Pedersen, January 9th, 2012 – http://www.reefs.com/blog/2012/01/09/we-are-noahs-ark-the-immorality-of-aquariums-debunked/

Juvenile production of Amphiprion bicinctus (Pomacentridae, Teleostei) and rehabilitation of impoverished habitats. Maroz A, Fishelson L. Marine Ecology Progress Series, MEPS 151:295-297 (May 22, 1997) – Abstract | Full Article as PDF

Very interesting article. I am actually performing a translocation experiment of A. occelaris in a former marine aquarium collection site in the Philippines for my graduate thesis. After doing an anemone survey in the area, i’ve noticed that there are barely any clownfishes left, which is probably due to the fact that prior to being declared a no-fish zone, it was actually an area with intense fishing pressure.

Originally, I intended on introducing tank-bred clownfish, but because of my lack of funding, I was unable to secure an outside source of quality fish. I would love to continue with the introduction of tank-bred clownfish if anybody is willing to donate their fish to conservation 🙂

RJ, thanks for that very interesting response. Of course, now you raise all the issues I didn’t discuss in the text above (because this article as not about reintroduction, or promoting reintroduction from hobbyist aquariums…which is exactly what you’re now discussing).

In our current state, A. ocellaris (and more importantly the Darwin Black form), and to a lesser extent A. percula, all are rapidly heading towards being hybridized into oblivion. Only if working with a trustworthy producer with stock of known source, would you even know if you’re getting genetically intact and correct fish. Plus, as Glenn Litsios has pointed out to me, A. ocellaris is actually made up of multiple genetic groupings, which means using the right “strains” for replenishment would be potentially important.

As such, your translocation program certainly seems like a better option for replenishment at this point in time…you’re know you’re bringing genetically intact specimens from one local area to another, presumably not over great distances. Of course, you’d have to consider the impact that collecting fish to relocate might have on the other population.

The next best thing of course, would be to bring select broodstock from the impacted area into captivity for dedicated propagation on site. Once again, no concerns of genetic integrity, and you have a constant supply of F1 fish for restocking efforts.

For now, captive-bred fish from the trade represent a failsafe, a last option when all others are exhausted. Among other reasons already mentioned, concerns over non-native pathogens being introduced into new parts of the world certainly have merit. Currently, there are better options than the trade. But should these options fail to work in situations like you outlined…should a species become “extinct in the wild”, it’s certainly better to have a “living gene bank” that was self funded from day one.

That said, it’s my hope that through better information, and ongoing discussions, some of the currently observed pitfalls and shortcomings of the “Aquarium Ark” can be mended and corrected. If we KNOW that this unseen, uncoordinated capacity exists, perhaps it can be better leveraged and managed, meaning that tomorrows breeders might be better equipped should our captive stocks one day be called into action for conservation purposes.

Hi Matt. Thank you kindly for your reply; I will definitely integrate your insights in my study. Actually, at first, I was in the process of breeding a pair of A. occelaris that I bought from a local aquarium fishermen, but the breeding exceeded my timeframe, so I decided to perform a translocation experiment instead. It’s a good thing that I didn’t outsource tank-bred specimens from unknown breeders since the expected output could be worse than my intentions of conservation, as you mentioned above.

I agree that the demand for hybridized forms of clownfishes are increasing, and you’re right, the idea of an “Aquarium Ark” would be a perfect source for conservation purposes if managed and documented properly. The question I have, and I think you raised very well in the article, is how can we create this paradigm shift for aquarists and breeders to focus more on wild-type specimens rather than hybridized forms?