An Orangefinned Anemonefish (Amphiprion chrysopterus) pair on their anemone. Palau, Micronesia. Image Credit – Subblefied Photography | Shutterstock

Genetics | Hybrids | Species Part 1| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6a | 6b | 6c | 6d | 6e | 7 | 8 | Index

The Challenging And Diverse Blue Stripe Clownfishes (Amphiprion chrysopterus)

From One May Come Many

by Matt Pedersen

Almost as soon as I learned of the very existence of such a stunning creature as a “Blue Striped Clownfish”, I learned that there isn’t just “one” Blue Striped Clownfish (Amphiprion chrysopterus). This species groups together many apparent races, or geographic variants. But before considering the diversity within this “species”, perhaps we should step back for a moment and think about this stunning clownfish at a very basic level.

One Of The More Difficult Clownfishes To Keep

Blue Stripe (or Blue Striped, Bluestriped, Orangefinned, Orange Fin) Clownfish are not “common” in the aquarium trade by any stretch, and yet they are very widespread. Their “rarity” has more to do with their suitability for captivity.

In the companion article to this series covering the basics of Clownfish species, Scott Michael wrote that, “The Bluestriped Anemonefish often has a difficult time adjusting to aquarium life…the fish tends to be a poor shipper and is also very susceptible to Brooklynella“. Indeed, this mirrors my own experiences.

My Personal Experiences with Blue Stripe Clownfish

The first time I ever saw a live Blue Stripe Clownfish it was a Fijian fish, with completely yellow fins and a beautiful yellow lyre tail. The asking price was steep in my opinion; $100 seemed like a lot for a fish covered in Cryptocaryon. Going against the typical wisdom to “avoid rescuing a fish from a pet shop”, I made an offer to purchase the fish at a vastly reduced price with the plans of getting it immediately into a hospital tank at home. Lucky for me, but perhaps not for the fish, the salesperson declined my offer.

The first time I acquired a juvenile pair of Blue Stripes from the Solomon Islands, they arrived looking great and went through a drip acclimation showing no signs of stress. I placed them in the quarantine tank, along with a couple other clownfish in another divided area. Both young blue stripes died within 30 minutes. The rest of the fish were fine.

The only good photo I ever got of my first Blue Stripe Clownfish, A. chrysopterus, these being sold as juveniles from the Solomon Islands. Image by Matt Pedersen

My next experience with wild-caught Blue Stripe Clownfish was quite recent; I came across the wonderful opportunity to purchase a pair of Marshall Island Blue Stripes from a vendor I’ve worked with repeatedly. The fish had been in his care for a month…very solid. They were vastly over-packed for the journey from Hawaii, and arrived in great shape.

Took one photo of a Marshall Islands A. chrysopterus in the bag – little did I know it’d be the only photo I’d ever take of these fish! – by Matt Pedersen

I gave them a nice long drip acclimation, going through a 5 gallon bucket twice, before adding them to a reef aquarium with anemones. The fish promptly dove to the bottom and wedged themselves underneath the live rock. For the next 48 hours, they were breathing incredibly heavily, and refused to come out. After five days, both fish had perished, the only outwards symptoms being stress. I’m very confident I can rule out disease or the tank itself; here’s why…

The only success I’ve had with Blue Stripe Clownfish to date came in the form of captive-bred juveniles of the Irian Jaya provenance, bred and exported to the US by Bali Aquarich. They have been model citizens, and ironically, were the immediately prior inhabitants of the reef tank I introduced the doomed Marshall Islands pair into (yes, I literally removed the Irian Jaya Blue Stripes the night before). One interesting observation; the fish were all well behaved with each other until I introduced several small Bubble Tip Anemones (Entacmaea quadricolor) to their aquarium – immediately they staked claims and started fighting with each other, causing one permanent eye damage and leading to a second to jump. Moving them back to a barren tank, they’re once again happy to coexist.

This captive-bred juvenile of Amphiprion chrysopterus “Irian Jaya” is proving to be a winner in terms of aquarium suitability – by Matt Pedersen

Why Don’t We See Wild Juveniles For Sale?

If shipping stress and argaubly deplorable track records in captivity aren’t enough to keep most aquarists away from the Blue Stripe Clownfish, what then of the smaller, presumably more resilient juveniles? Many reef fishes fare better when collected and shipped while relatively small; being perhaps less set in their ways, and easier to accomodate in shipping, juvenile reef fishes are also often less expensive. Not to mention that the harvest of smaller juveniles is generally thought to have less of an impact on populations than the removal of reproductively active adults.

Once again, the Blue Stripe falls short – even if the juveniles were predisposed to do better on the journey from the reef to our home aquariums, they’re unattractive. That’s right; juvenile Blue Stripes lack their namesake coloration, and are generally a medium shade of brown. They are arguably among the most unattractive juvenile in the entire Clarkii-complex, so they aren’t collected, and aren’t sold (for a good example, see this image of Blue Stripes in Palau, two adults, and note the very blandly colored juvenile at upper right).

Indeed, it’s fair to say that for all the grief outsiders throw at the aquarium livestock industry, the reality is that it actually has, over time, proven itself to be fairly good at self regulating what it offers. This is the reason why difficult species, like the Blue Stripe Clownfish, are in fact very hard to come by, and when you do find them, they carry a higher price tag in part due to vendors giving these fish far more packing space than a counterpart like Amphiprion clarkii. And because fish like the Blue Stripe Clownfish are largely shunned as adults due to a difficult reputation, and only rarely imported as juveniles due to their drab coloration, the average aquarist doesn’t even know the Blue Stripe Clownfish exists. Even the average clownfish lover might not understand the reason why I’d be talking about particular locations like the “Solomon Islands”, “Irian Jaya”, “Fiji” or “Marshall Islands” as if they should mean something.

An adult Blue Striped Clownfish is a sight to behold, this one from Tutuila, American Samoa – Image by NOAA/NMFS/PIFSC/CRED, Coral Team

Finding Aquarium Success With The Blue Stripe Clownfish

Despite all the setbacks and obstacles this species presents, if you can get over the initial hump of transport stress, and avoid what many would make me believe is the almost inevitable Brooklynella outbreak, Blue Stripe Clownfish are wonderful; at least that’s what everyone tells me.

“Bluestripes aren’t difficult to maintain once healthy in captivity, but spawning them can be tricky,” said Matthew Carberry, president of Sustainable Aquatics. “Natural tanks (large, with anemones) work better than the smaller ones used for most other species [in my experience].”

Carberry’s comments lead right into my point – Blue Stripes are a great example of how captive-breeding can make a “difficult fish” easier; my “Irian Jaya” Blue Stripes almost seem bulletproof by comparison to the wild fish I’ve tried. But getting captive-bred Blue Stripes isn’t easy as Carberry tells it…and to date it appears that Bali Aquarich is the only company making this species commercially available.

But this is where it gets interesting…is there really just “the species”…as in “one” species of Blue Stripe Clownfish?

Marine Fish Don’t Have “Geographic Variants”!

Freshwater aquarists are very accustomed to geographical variations within species and species clusters; for me it is the diversity of Cichlids in Lakes Malawi and Tanganyika that best demonstrate this concept. While I’m probably over-simplifying this a bit, I’ll just suggest that populations might only be separated by a few dozen miles, and yet appear remarkably different from one reef to another. These variations are caused by the lack of gene flow between populations; something as simple as a wide sandy beach may prevent rock-loving fish from traveling between, and thus, distinct populations arise.

Marine aquarists are not prone to think about marine fish as having variations within a species. In fact, the vast majority don’t. It could be argued that extended pelagic larval phases allow for larval fish to travel great expanses, allowing for gene flow from one reef to the next, one island group to another, overcoming what would at first appear to be isolation. I recall reading that the great range of species like the Longnosed Butterflyfish (Forcipiger flavissimus) and the Moorish Idol (Zanclus cornutus) is generally attributed to these species having greatly extended larval durations. In fact, only a handful of marine fish lack a pelagic larval phase (and are considered to be “direct developers”). So why would anyone even look for species variations between different populations? It’s just not expected in the first place.

Unexpected Color Variantions in Amphiprion chrysopterus

The first I remember learning that not all Blue Stripe Clownfishes looked the same, was probably a discussion in a forum with a casual mention that some Blue Stripe Clownfishes have Yellow Tails, while others have White Tails. At first, I probably took this to mean some sort of polymorphism – color variations within a population. Pretty rapidly, I came to understand that these variations were not polymorphsim, but was representative of different geographic forms.

One of the longest standing online references to this color variation that I can recall is on the BlueZooAquatics.com website, which states: “The Blue Stripe Anemonefish from Fiji and Tonga have YELLOW tails, and the Blue Stripe Anemonefish from Solomon and Marshall Islands have WHITE tails.”

The actual Blue Zoo Aquatics Currator’s Note that first tipped me off to the true nature of variation in A. chrysopterus

Meanwhile, the defacto clownfish reference of the day, Joyce Wilkerson’s book Clownfishes (2003), made no reference to any color variation within populations of Amphiprion chrysopterus, only citing a “widespread distribution in the Western Pacific, from Taiwan to Polynesia”. Scott Michael’s 2008 Damselfishes & Anemonefishes, made no mention of color variations in the text, but did cite a “white tailed morph” in a photo caption.

It wasn’t until my clownfish library grew to include some older books, that I came across any printed references to any sort of variation being mentioned.

John H. Tullock’s 1998 publication Clownfishes and Sea Anemones barely mentions the species at all, which could also be said for Gregory B. Skomal’s handbook Clownfishes In The Aquarium. Daphne G. Fauntin & Dr. Gerald R. Allen’s 1992 publication, Anemone Fishes and their Host Sea Anemones, is in fact the only printed record I have which acknowledges the color variation of Amphiprion chrysopterus.

When denoting the coloration and features of the species, Fautin & Allen wrote, “Brown to nearly black with two white or bluish-white bars and a whitish caudal fin; over most of the western Pacific all other fins are yellow orange, but fish from Melanesia have black pelvic and anal fins.” Dr. Allen’s earlier 1980 book, Anemonefishes of the World, also shares a comparable observation regarding the coloration of A. chrysopterus.

It is fair to say that, in terms of publicly accessible information, it was Blue Zoo Aquatics, not a scientist or author, who had published the most complete information regarding the coloration variation of Amphiprion chrysopterus in the wild.

Enter Kylie Waldon

I’ll cover Kylie Waldon’s contribution to clownfish understanding more in the next segment of this series, but I must bring her work up at this point. Waldon’s website, Anemonefishes In The Wild, went offline apparently in 2007. But it was online long enough for me to save it locally, and it is still accessible via Archive.org.

Waldon pioneered a new way of researching anemonefish variation by data mining photography both online and in print material; any pictorial reference showing a clownfish with a given location was cataloged, the fish’s coloration and pattern sketched. Her cataloging of Amphprion chrysopterus painted the most complete picture of clownfish biogeographic variation for its time.

Waldon’s work isn’t perfect, but she was careful with her records; each individual fish can be clicked and investigated for further details, including an exact reference if known. A few of Waldon’s fish don’t “fit” the story I’m about to weave, but it turns out that these misfit fish generally don’t have steady, reliable geographic provenance associated with them. When a fish “may be from Fiji” but doesn’t match up with what we know to be found in Fiji, I’m inclined to discount that data point.

This shouldn’t really be surprising. After all, virtually every online photograph of “Amphiprion chrysopterus” in the “Philippines” is actually Amphiprion clarkii upon closer inspection (for example this “Puerto Galera” Chrysopterus, or this nearby “Lembeh Straits” Chrysoputerus, both of which are clearly Amphiprion clarkii). It would appear that A. chrysopterus does not exist in the Philippines, nor most of Indonesia. Despite a few shortcomings that are easily recognized, Waldon’s work very firmly demonstrates the existence of A. chryopsterus variants at several geographic locations.

Enter Litsios Et. Al.

It wasn’t until I read The radiation of the clownfishes has two geographical replicates, by Glenn Litsios, Peter B. Pearman, Deborah Lanterbecq, Nathalie Tolou and Nicolas Salamin, earlier this year in preparation for my Marine Breeding Initiative (MBI) presentation on Clownfish variations that something clicked. As I wrote earlier, the authors of this paper recognized a distinct genetic distance between “the White-Tailed form of Amphiprion chrysopterus which is found at the Solomon Islands” and the “Yellow Tailed forms found at Moorea and Fiji.”

I hadn’t looked at Waldon’s work for quite some time; it sat on my hard drive collecting cyber dust, but I had “brought it out” in preparation for my talk at the end of July, 2014. The authors of the 2014 paper had only examined A. chrysopterus from 3 locations (Fiji, Moorea, Solomon Islands), but I knew Waldon has covered many more, including Papua New Guinea, Fiji, New Caledonia/Australia, “Indonesia”, Palau/Guam/Marshall Islands, Tahiti, Niue, and “South” Pacific.

Taking A Lead from Kylie Waldon and Yuri Barros

Another clownfish enthusiast active on the internet a couple years ago, Yuri Barros, had taken a lead from Waldon. In 2011 and 2012, Yuri maintained and updated a photo collection of clownfish variants gathered from around the internet, posting them in a forum thread simply called “Rare Fishes” on the now defunct internet forum website RareClownfish.com. Unlike Waldon’s work, Barros’s forum posts didn’t weather the internet so well; most of his public writing was lost, and none of the supportive images saved, via Archive.org. Only pages 1, 2, 3, 11, and 12 were retained by Archive.org. None of these covered Barros’ observations and thoughts on A. chrysopterus, and I had been unable to find any way to reach out to him earlier in the year when compiling my MBI talk.

While his posts were lost to me and with it, the information contained, I remembered the overall concept – gather data by simply looking for all the photos you can find. Of course, one of the most important areas that gets overlooked is video-based data too, so I considered that whenever possible as well. But I took it one step further, and I owe Dr. Luiz Rocha’s talk on the Speciation of Reef Fishes for making me think this way. When I gathered my data, I put it on a map.

The Data

Google image searches and photo licensing websites became an instant data source. These days, dive photos and videos from people’s trips are ubiquitous. Folks don’t generally “lie” about where they’re shooting (after all, isn’t part of the journey that you get to brag about exactly where you went?) so for the most part, photos that include a location are pretty reliable. I wouldn’t say 100%, but certainly a respectable level.

I’m going to refrain from classifying the data any further at the moment. I started by simply linking known populations with the online information I was able to gather (please note as time passes, some of this data could be removed from the public space…that’s the nature of the internet).

From, roughly west to east, here is what I plotted against:

- Komodo, Indoesia

- Cenderawasih Bay, West Papua, Indonesia

- Palau, Micronesia

- Yap, Micronesia

- Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea

- Mandang, Papua New Guinea

- Guam

- Saipan, Mariana Islands

- Caroline Islands, Micronesia

- Great Barrier Reef

- Osprey Reef, Coral Sea, Australia

- Chuuk, Micronesia

- Coral Sea, Australia

- New Caledonia (brown phase)

- Pohnepei, Micronesia

- Solomon Islands

- Kosrae, Micronesia

- Vanuatu

- Marshall Islands

- Fiji

- Tonga

- Phoenix Islands, Kiribati, Polynesia

- Tutuila, American Samoa

- Swains Island, American Samoa

- Niue

- Bora Bora

- Mo’orea

- Tahiti

- Rangiroa, Tuamotu Islands

I should note, that in many cases, there were dozens of photos for a given locale. In other cases, only a single reference could be found. I believe what I’ve linked above to be representative as a whole.

Plotting The Data

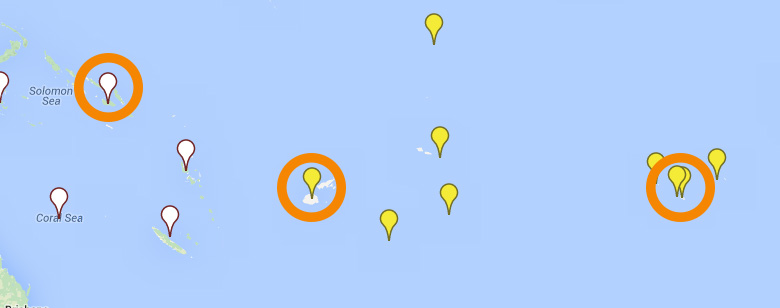

Initially, I approached this project as a simple experiment with a very simple question in mind – where are the White Tail forms found, and where are the Yellow Tail Forms found.

As I found representative records, I simply plotted them on my Google map, and I classified what I found as White Tail or Yellow Tail.

This was the first plot.

The plot showing White Tail (white marker) and Yellow Tail (yellow marker) forms of Amphiprion chrysopterus – map via Google Maps, plot by Matt Pedersen

I was shocked.

The Discovery – Three Base Phenotypes

As I had gone through the steps of gathering up photographic references, it had become very clear to me that there was more than just “White Tail” and “Yellow Tail” going on here. Of course, Litsios et. al. had put me in that White Tail vs. Yellow Tail frame of mind, but there was something else. Here’s the three geographic locales that Litsious et. al. had sampled for their genetic study:

The locations of A. chrysopterus in Litsious et. al.; Solomon Islands (left), Fiji (center), Moorea (right).

What was missing is the fact that there aren’t simply White Tail and Yellow Tail forms of Amphiprion chrysopterus; it’s more complex. Dr. Allen knew it because he mentioned it decades earlier, and Waldon’s illustrations, combined with data from Blue Zoo, illustrated that there are at least three fundamental forms of Amphiprion chrysopterus.

For the most part the fishes shown by Waldon and the image / video data I collected can be grouped into three basic color schemes. The first two forms are the types that Allen describes in his books.

White Tails, Yellow Fins

A. chrysopterus from Palau, as we opened this article with, is a good representation of the White Tail, Yellow Fin phenotype of Bluestriped Clownfish. Image by Subblefied Photography | Shutterstock

The first group is what I will call White Tail, Yellow Fins, or WT/YF. This group consists of fish from Palau (the type location of A. chrysopterus), Yap, Pohnpei, Chuuk, Vanuatu, Kosrae, the Marshall Islands, the Caroline Islands, and New Caledonia. Additionally, there is documentation showing this form in the Coral Sea, and a somewhat questionable ocurrence at the far west of this species range in Indonesia at the Komodo Islands (more on that below).

White Tail, Black Lower Fins

A. chrysopterus at Milne Bay, PNG – if you look through the anemone tentacles you can tell that the entire undercarriage of this fish, the anal and pelvic fins, are black. This is representative of the White Tail / Black Fins phenotype. Image by Scott Michael

The second group that becomes apparent is White Tail, Black Anal & Pelvic Fins, or WT/BF. This form can be found at Irian Jaya (West Papua), PNG (Papua New Guinea), the Solomon Islands and Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

Yellow Tail, Yellow Fins

A. chrysopterus from Fiji, a good representative of the Yellow Tail, Yellow Fin phenotype – image by Cameron Bee / Walt Smith International

The third group is the Yellow Tailed forms mentioned by Blue Zoo Aquatics but overlooked in Allen’s published work; these are Yellow Tail, Yellow Fins, and thus, YT/YF. Forms with this arrangement are all at the eastern region of this species’ range, including Fiji, Tonga, American Samoa, the Phoenix Islands, Niue, as well as Tahiti, Mo’orea, Bora Bora and the Tuamotus Islands.

Reexamining The Data

When I re-plotted my data points considering these three groups, this is what the map looked like:

The plot showing White Tail + Black lower Fins (WT/BF – white marker), White Tail with Yellow Fins (WT/YF – orange marker) and Yellow Tail/Yellow Fins (YT/YF yellow marker) forms of Amphiprion chrysopterus – map via Google Maps, plot by Matt Pedersen

It starts to get even more interesting when you plot this not simply against geography, but against the known biogeographic barriers in the Pacific region. Take for example, overlaying my points on a map depicting the geographic plates of the region:

Biogeographic distribution of Amphiprion chrysopterus phenotypic groups overlaying a map of Pacific Plates. – Plate map from http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/97/Pacific_Plate_map-fr.png

And the real kicker for me; consider the distribution of these forms when plotted over a map of the region’s ocean currents; think about currents as you think about larval reef fish floating from one area to another…

Biogeographic distribution of Amphiprion chrysopterus phenotypic groups overlaying a map of Pacific Ocean currrents – current map from http://science.psu.edu/alert/photos/research-photos/biology/Baums_Pac_Map_Sample_Sites.jpg

Now, some of you may be thinking “so what”, but I know others (hopefully) among you are starting to connect the dots. We already have some genetic evidence that suggests that there is a big difference between two of these phenotypes, the WT/BF an YT/YF types. When we look further, we see this third phenotype, WT/YF, separating the two tested populations. We need more data at this point; would testing the White Tail, Yellow Fin forms, provide a connection between the two more disparate groups? Are we looking at two species? More? At this point, I shared what I plotted with Dr. Rocha…I felt it to be very compelling.

I found Yuri Barros!

Meanwhile, my data gathering had resulted in a random image result that turned up Yuri Barros, alive and well and posting on ReefCentral about, surprise, brown morphing that occurs in Amphiprion chrysopterus! It took some doing, but I made a connection and through Facebook literally the same day I had reached out to Dr. Rocha with this information. I was able to share my findings with Barros, and he, in turn, was able to make available to me his own observations on the “species” which, to a great extent, mirror my own! But Barros initially took it one step further,

Barros’ 4th and 5th Phenotypes

Barros was quick to redirect my attention to the far eastern forms of Amphiprion chrysopterus, specifically those from Tahiti, Mo’orea, the Tuamotus Islands, and Bora Bora. As soon as he pointed me to it, once again, it clicked.

These 4 easternmost populations are all Yellow Tail, Yellow Fin, but they are further more similar to each other, and dissimilar, to the other Yellow Tail / Yellow Fin forms forms to the west in Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, Niue, and the Phoenix Islands. These easternmost populations have what I would describe as lighter body coloration and narrow bars. It’s also noteworthy that their headstripe often does not connect dorsally like the headstripes of their relatives. I’ve shorthanded this 4th form as YT/YF/NB (narrow bar).

Amphiprion chrysopterus in Tahiti demonstrates the “narrow band” aspect of this unique group clustered at the far eastern edge of its range – Photo by MironCaro – Flickr | Creative Commons BY-ND

I think it’s fair to say that Barros believes these to be a distinct species. That said, Litios et. al. tested both a specimen from Fiji (YT/YF) and from the distinct eastern group from Mo’orea, and found them genetically similar. Outwardly, the visual difference is apparent, but these two forms are definitely more similar to each other than to the WT/BF form from the Solomon Islands.

Since our initial chats, Barros and I have continued to stay in touch and he’s continued to look at the photographs, pretty much the same photos as I am. Barros has decided that the 5th population group to the north in Guam and the Mariana Islands, is distinct as well despite being a Yellow Tail, Yellow Fin cluster. Barros claims this region is an overlap and may include both White Tail and Yellow tail forms. I’m not convinced yet. I wonder if perhaps at one point the northern populations were joined with similar phenotypes to the southeast, but relatively recently separated. Genetic testing to the rescue here too?

The “Bad Data”

It’s of course, not a perfect world, and no good scientist hides away the “bad” points. But I will put them down here towards the bottom.

As alluded to earlier, Waldon’s work is not 100% consistent with the photographic data I or Barros have collected. Some of her data points are openly disclosed as questionable; print references are often incomplete and point to long gone print materials…overall though Waldon’s work across all species seems to mesh well with what we know from more modern sources and as such, it’s still a good starting point.

The Mixing at Guam and the Marianas

Guam and the Marianas to the north remain a mystery. It is very clear that the fish in this group are by and large yellow tails, although there seems to be occasional “hints” at off white/pale yellow caudal fins. Guam is a little bit more difficult to pin down, but if we cluster these two locations as one, overwhelmingly modern references point squarely to YT/YF fish.

Waldon claims the form found in Guam is actually the white tail, yellow fin form, and cites an image taken by Ron Shimek, who happens to be a regular CORAL Magazine and Reef2Rainforest.com contributor. To cite Dr. Shimek’s own response – ” I have transited through Guam to points SW (Yap, Palau, etc.), but never was in the water at Guam. Additionally, I have no images of Amphiprion chrysopterus.” Which means Waldon’s sketch is, at minimum, miss-attributed, but more likely just something completely in error.

Additionally, a video from southern Guam clearly shows yellow tail, yellow fin chrysopterus (see the 5 minute mark).

Reviewing the GuamReefLife photo archives of A. chrysopterus, we once again see that the vast majority of fish depicted from Guam are Yellow Tail, Yellow Fin variants, and very striking ones at that. There are, however, a couple images of fish that are called out as A. chrysopterus with white tails (see example #1 and #2) – these fish would fall into a phenomenon of “brown morphs” which Yuri Barros has noticed while cataloging wild images, and it would seem that captive fish can switch to this color form (generally disappointingly for their owners). That said, I’ll propose an alternate idea – perhaps these wild “Brown Morph” fish are actually hybrids with sympatrically occurring A. clarkii. That would certainly explain the orange pelvic fins and outlined stripes seen in these photos (again, see example #1 and #2).

Still, Barros shared an image from the Saipan Island, Northern Marianas, that certainly demonstrates sympatrically occurring white-ish tails within this overall yellow-tailed group. Perhaps the records (and rumors) of white tailed fish occasionally occurring in Guam and the Marianas can be explained by the occasional white tailed larvae that is able to make the journey north, arriving from Yap, the Caroline Islands, or Chuuck, in western Micronesia.

Sympatric Forms of A. chrysopterus at Osprey Reef

The only other area where phenotypes were up for debate seems to occur at Osprey Reef in the Coral Sea. Here, I’ve found photos of WT/BF (this form dominates numerous), WT/YF, and a singular “mixed” form which had White Tail, Yellow Anal Fin, and mostly Black Pelvic fins. Barros and I looked at this fish and I believe we both came to the same conclusions – when I look at the ocean currents, we have WT/BF larvae arriving from the north, including PNG and the Solomon Islands, while WT/YF larvae drift over from the east, at Vanuatu and New Caledonia. So it is very conceivable that Osprey Reef in the Coral Sea, adjacent to the Great Barrier Reef, represents a mixing of the waters. Since larval leaving this region may go south into the open ocean with no reefs to colonize, any mixing that occurs at Osprey Reef probably has no impact on the populations to the north or the east.

In the end, these isolated WT/YF and the mixed forms at Osprey Reef and the Coral Sea are probably explainable in the exact same way that these forms are explained where the WT/YF form borders the YT/YF forms of Guam and the Marianas.

A. chryopterus Where It Doesn’t Exist

It would seem that the entirety of the western extremes of the Blue Stripes reported range might be invalid.

As I stated earlier, every “Philippine Chrysopterus” I looked at turned out to be A. clarkii; check out this example on a photography website, which clearly shows A. clarkii mislabled as A. chrysopterus, reportedly from Puerto Galera in the Philippines.

I’ve found no mention that A. chrysopterus should even occur in Indonesia (What we generally think of as “Indonesia” it is clearly excluded in Dr. Allen’s published range maps). Technically, the “Irian Jaya” / West Papua form is from within Indonesia, but objectively Irian Jaya / West Papua is just the western half of the island of New Guinea, and as such, the distinction is one of a political boundary, and not one of geography. In my opinion, it seems that all the references to A. chrysopterus occurring in the Philippines, Indonesia (save the New Guinea landmass) and Vietnam are probably cases of mistaken identity with A. clarkii.

That said, there is a singular photographic reference placing the species at the Komodo Islands within Indonesia. It is perhaps bad enough that the anemone in the photo, clearly Entacmaea quadricolor, is misidentified as Heteractis magnifica. Not to mention that a specimen of A. clarkii is residing in the anemone. So dubious is this photo, that it’s the only photograph I’ve looked at and wondered, ” is that Photoshopped?” In other words, outwardly it appears that the white-tailed, yellow-finned A. chrysopterus in the photograph was “added”. I’m highly inclined to discount this data point.

From One May Come Many – up to 4 new species split out of Amphiprion chrysopterus?

Despite some data at the “fringes” that seems questionable, overall it’s my opinion that loads of internet-based data in the form of photographs and videos with locations attached has strongly supported the distributions I’ve plotted. Based on this, it’s fair to demonstrate at least three or four unique phenotypic groups within our observed fishes.

I am very comfortable in suggesting that we will see, at some point in the future, a new species described out of the Chrysopterus-complex, and maybe two new species. We should remember that the type location for this species is Palau; a white tail, yellow fin form from the more western part of the range, a phenotype that has not been subjected to any genetic testing or comparison. Therefore, A. chrysopterus would remain applied to that Palau form, and presumably the other White Tail, Yellow Fin forms (WT/YF) in the region including common trade locations like the Marshall Islands.

The White Tail, Black Fin form actually follows the species distribution of Amphiprion percula quite similarly. If further investigation determines that these WT/BF forms are not the same species as the WT/YF forms, these very dark fish could be up for a new name, particularly if some genetic testing separated it out nicely from the forms from Palau, the Marshall Islands and others.

It seems even more likely that the eastern Yellow Tailed forms, both the YT/YF and YT/YF/NB which are greatly separated both biogeographically and likely genetically from the western white tailed groups, could well wind up with a new name. If we think about the descriptions of both Amphiprion pacificus and A. barberi in Fiji / Tonga, these forms are biogeographically isolated (particularly the rift between A. melanopus and A. barberi) in the same manner that the Fijian and related populations of Yellow Tail A. chrysopterus are separated from the White Tail forms.

Amphiprion chrysopterus in Bora Bora, the far eastern “narrow band” group with Yellow Tails, and Yellow Fins, Narrow Bands and unconnected head stripes. Image by SF Brit – Flickr | Creative Commons BY-ND

What remains to be seen is whether the extreme eastern cluster, those with narrow bands, would wind up being considered distinct enough from the other Yellow Tail forms, but it’s certainly worth investigation.Whether the ‘fringe’ groups to the north and far east would get new names, that to me is a harder question to answer. But if they did, what was once all considered one species could suddenly become five.

UPDATED – A final plot showing all the phenotypic groups of Blue Stripe Clownfish. Group 1a includes the type location for Amphiprion chrysopterus in Palau. 1b is another WT/YF population to the south, sandwiched between 2 and 3, and includes the possible overlap of two forms somewhere in the Coral Sea. 1c is the dubious / suspect photo record of A. chrysopterus in Komodo, Indonesia, where it likely doesn’t belong. 2 is the Blackfooted, or White Tail / Black Fin form from “Melanesia”. 3 is the classic YT/YF form found in Fiji and Tonga. 4 is the YT/YF/NB group found at the far east of the range, with 5 being a far separated YT/YF population to the north. – map via Google Maps, plot by Matt Pedersen

Why Provenance and Geography Matter

Breeders long understood that the mating of a Yellow Tail and White Tail form of Blue Stripe Clownfish, while technically not an interspecific hybrid per current taxonomy, was simply a bad idea. If nothing else, it wasn’t going to give offspring that were good representations of either parental form. In truth, I believe it would be vastly blurring species lines, creating something that in no way represents the “species” as it exists in the wild.

Amphiprion chrysopterus, and its vast diversity of forms, is perhaps only superseded by its relative, Amphiprion clarkii. Barros believes and attempts to demonstrate that there may be up to 10 unique forms (distinct species?) all currently lumped together in A. clarkii.

As shown before with a brief history of Amphiprion barberi, taxonomy likely will change, and knowing what you have (and keeping it true to form) will have little to do with taxonomy, and everything to do with fish that carry a known collection location all the way from the diver to you. I believe the traceability required maintain the integrity of such information can only help foster additional transparency in the marine aquarium fish supply chain, and that is a good thing for every marine aquarist, and every wild fish we wind up keeping.

Continue to the next section – “Geographic Variants Within the 30 Current Species of Clownfishes“

Genetics | Hybrids | Species Part 1| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6a | 6b | 6c | 6d | 6e | 7 | 8 | Index

References

You can read an online version of Fautin & Allen’s Anemone Fishes and their Host Sea Anemones – note that the images in the online version are not the same as the ones published in the book, so we’d still suggest getting a hard copy if you can find one (it is much better in print!)

Litsios, G., Pearman, P. B., Lanterbecq, D., Tolou, N., Salamin, N. (2014), The radiation of the clownfishes has two geographical replicates. Journal of Biogeography, 41: 2140–2149. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12370

Image Credits – see captions

Hi Matt, I’ve read your article/research here on Blue Stripe Clowns with great interest and a bit of sadness really! I recently purchased from a local shop a pair of clowns that were sold as “blue stripe”…although they have a light blue hue, depending on viewing direction and light spectrum on my tank, they also have a 3rd stripe at the base of their tale and the tale is yellow, whereas body is dark brown and orange…are these therefore normal clarkii clowns??? Thanks; Enzo

Enzo, do you have photos posted anywhere that we could take a look at? That would help tremendously with identification. There are Clarkii at times that show blueish stripes, so that is certainly a possibility.