The following partial excerpt is a selection from “Playing With Matches: Hybrid Clownfishes” by Matt Pedersen. Get it now in the September/October 2014 issue of CORAL Magazine

Genetics | Hybrids | Species Part 1| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6a | 6b | 6c | 6d | 6e | 7 | 8 | Index

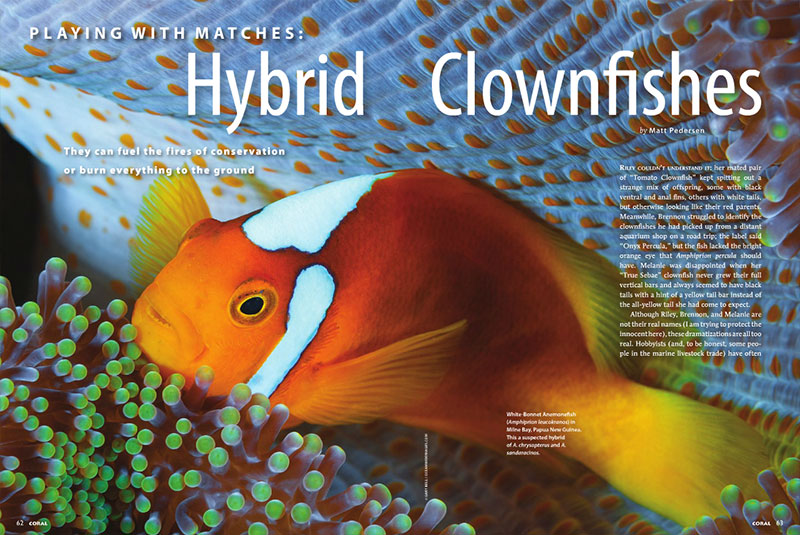

Playing With Matches: Hybrid Clownfishes

They can fuel the fires of conservation or burn everything to the ground

by Matt Pedersen

RILEY COULDN’T UNDERSTAND IT: her mated pair of “Tomato Clownfish” kept spitting out a strange mix of offspring, some with black ventral and anal fins, others with white tails, but otherwise looking like their red parents. Meanwhile, Brennon struggled to identify the clownfishes he had picked up from a distant aquarium shop on a road trip; the label said “Onyx Percula,” but the fish lacked the bright orange eye that Amphiprion percula should have. Melanie was disappointed when her “True Sebae” clownfish never grew their full vertical bars and always seemed to have black tails with a hint of a yellow tail bar instead of the all-yellow tail she had come to expect.

Although Riley, Brennon, and Melanie are not their real names (I am trying to protect the innocent here), these dramatizations are all too real. Hobbyists (and, to be honest, some people in the marine livestock trade) have often struggled with the identification of many anemonefishes at the basic species level. And now, at a time when it can still be difficult for the casual hobbyist to differentiate between a Tomato and a Cinnamon Clownfish, we are starting to have to contend with hybrid fishes. Some hybrids are clearly labeled and sold as such, but things can get hopelessly complicated by small-scale breeders who inadvertently create hybrid pairings and sell the offspring as whatever pure species they resemble. Hybrids blur subtle differences between the parental forms, and in the end it can be very easy to mistake them for actual pure species.

Even more sinister are those breeders who intentionally create hybrids and sell them as pure species because they believe the hybrids have an advantage in appearance over the true species. An overseas breeder some years ago openly admitted to selling Percula X Ocellaris as a straight-up “Mango” Ocellaris or some other fanciful strain name. He bragged to other breeders that he got higher prices and brisker sales on these “Percularis” than his competitors got for pure Ocellaris.

2014 HYBRID CLOWNFISH REVIEW

If the world of clownfish breeding and marketing seems more than bit frenzied at the moment, it helps to know that hybrid anemonefishes can be sorted into four groups.

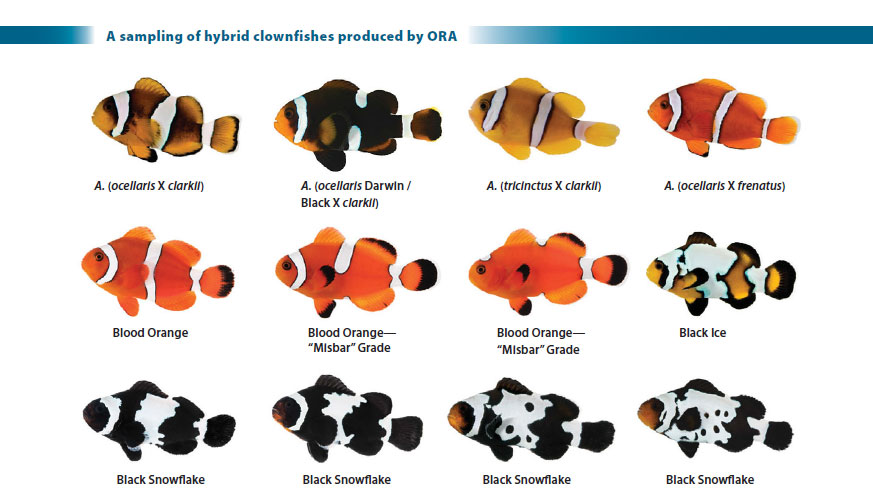

A sampling of various types of intraspecific, interspecific, and intergeneric clownfish hybrids produced by Oceans, Reefs & Aquariums (ORA) – see many many more in the full article.

“Natural” Hybrids

Once again, as with “designer” morphs that turn up in natural wild populations of Amphiprion and Premnas spp. fishes, we find that Mother Nature is not the straight-laced, stern headmistress she is often made out to be—hybrid fishes are far from rare within reef communities. We define “natural” or “wild” hybrids as those found in nature without any direct human intervention. Certain hybrids are definitely part of the natural biodiversity in the reef. Some of the “pure species” today may have well been the result of two wild species merging through hybridization countless generations in the past.

Intraspecific Hybrids

This group represents a gray area where contested taxonomic definitions cause aquarists to disagree about whether these pairings represent matings between two different species or one unified species. Thus, an intraspecific hybrid would be defined as a cross between different phenotypes or geographic forms of taxonomically same-species clownfishes. The mating between Yellowtail and Whitetail geographic races of the Bluestripe Clownfish, A. chrysopterus, is one such example.

Interspecific Hybrids

Interspecific hybrids are offspring resulting from the mating of different species (primary hybrids), a species and a hybrid, or even two hybrids (secondary or complex), all within the same genus.

Intergeneric Hybrids

In the world of clownfishes, there are only two genera: Premnas and Amphiprion. In order to create an intergeneric hybrid—one that crosses genus lines—you have to incorporate some sort of Maroon Clownfish. Intergeneric orchid hybrids are given made-up botanical genus names that combine the genera of the parental species; whether or not we need to do that in clownfish breeding is unclear, but if we did, some group of breeders would have to get together and decide between the endless possibilities: Pramphiprion, Premprion, Premphiprion, Premnion, Premnasion, Premnamphiprion?

Log in with your digital subscription to see the stunning pictorial spreads showing dozens of wild and man-made hybrids right now, or buy the spectacular print back issue today!

THE DANGERS OF HYBRIDS

The fact that hybridization cannot be undone sits at the core of generally negative sentiments toward hybrids. For conservation biologists, “hybridization” is generally a dirty word, inasmuch as hybrids can lead to the loss of distinctive species. For those of us in the aquarium world, and especially breeders, it is their potential to be passed off as pure species, and thus their ability undermine the work of maintaining wild-type strains of fish, that raises concerns about hybrids.

Conservation aside, hybridization at low, ongoing levels can severely impact the aesthetics of a pure species. A striking example of this was recently documented in Lake Victoria. Researchers discovered two sympatric cichlid species sharing a common range, normally quite distinct and vibrant, in a location where the mate selection processes broke down and allowed hybridization to occur. The now impure populations appear muddled, muted, and simply less attractive.

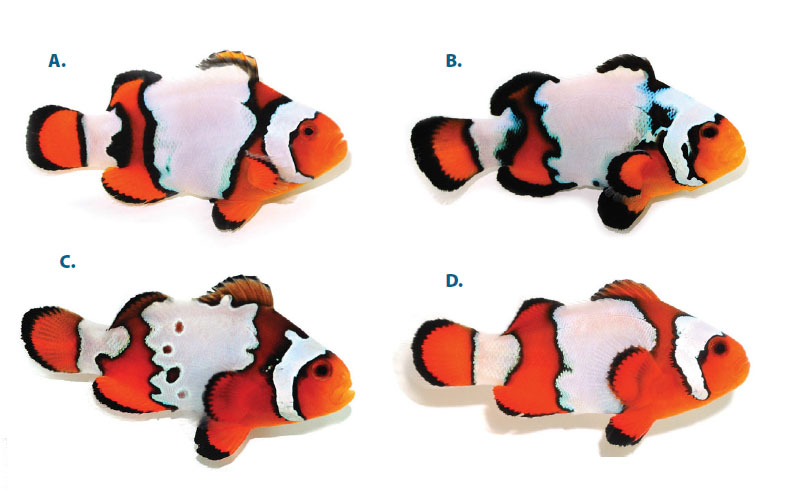

Pop Quiz! Can you tell which fishes are hybrids and which are pure species? Can you tell what each one is named just by looking? See answers on page 66 of the Sept/October 2014 issue of CORAL Magazine.

WHY DO WE CREATE HYBRIDS?

Hybridization often appeals to breeders, particularly those who have yet to understand the need for a conservation ethic, for a few reasons. First: vanity. We’re all guilty of wanting to “do something new,” and the instinct runs especially strong among breeders of aquarium fishes. In fact, it’s relatively easy to create a new hybrid. By comparison, it can take two to ten years and thousands of dollars to investigate an aberrant form once it is discovered and obtained, and in the end, the aberration might not even be genetic and heritable.

At a commercial level, hybridization can be very appealing. Hybridization, particularly creating primary hybrids between species, offers instant and replicable results. There is the added benefit that there isn’t a wild fishery to compete with.

Hybrids between disparate species are generally very unique; the Amphiprion (clarkii X frenatus) hybrid won’t be confused with any pure species, so it’s somewhat benign. However, you can’t make this hybrid without the species. When I set out to recreate this hybrid, I need to breed (or find) purebred Tomato and Clarkii clownfishes too, which I never would have done otherwise. A hybrid like this may well be beneficial, creating a need to preserve the parental species, even if only so we can remake the hybrid!

How many named hybrids are out there? How are they created? See the naturally occurring, visually stunning hybrid of Amphiprion (clarkii X frenatus), and dozens of others, in the complete article published in the September/October 2014 issue of CORAL Magazine. Grab a copy from your local aquarium shop before they’re gone, or order online to secure your back issue today. Be sure to subscribe to CORAL Magazine so you don’t miss out on thought-provoking content like this again!

Read the next installment – Clownfish Diversity: A Treasure and A Challenge

Genetics | Hybrids | Species Part 1| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6a | 6b | 6c | 6d | 6e | 7 | 8 | Index

Image Credits:

The naturally occurring hybrid, Amphiprion leucokranos, in the wild – Gary Bell / OceanWideImages.com

Examples of various captive produced hybrid anemonefishes – images courtesy ORA

Clownfish Pop Quiz – images courtesy Sustainable Aquatics

Trackbacks/Pingbacks