Aquarists have come to know about certain variants in the closely-related Maroon & Ocellaris group; Gold Stripe Maroon (top left), classic White Stripe (top right), Darwin Black Ocellaris (bottom left) and classic Orange Ocellaris or “False-Percula” (bottom right). Sea & Reef Aquaculture routinely produces all these variants, but would you be surprised to know there’s still more out there? Images by Sea & Reef Aquaculture

Genetics | Hybrids | Species Part 1| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6a | 6b | 6c | 6d | 6e | 7 | 8 | Index

Geographic Variants Within the 30 Current Species of Clownfishes – Maroons, Ocellaris & Perculas

Considering the prior observations of Anemonefish enthusiasts, and surveying the observed geographic variants of Anemonefishes by Matt Pedersen

Maroon Complex

Premnas biaculeatus – The Maroon Clownfish does exhibit some variation across its range. We’ll consider this species, and the three groups contained within, roughly traveling west-to east.

#1. The well-known and highly documented “Gold Stripe” form from Sumatra is quite possibly in need of reconsideration as a unique species, perhaps resurrecting Premnas epigrammata, the species from Sumatra described by Fowler in 1904. I have argued earlier that Gold Stripe Maroons are likely candidates for reexamination, and perhaps the restoration of P. epigrammata as their taxonomic rank. It is important to note that Gold Stripe Maroons are notorious for losing their stripes, from the bottom up, as they age. Individuals with incomplete stripes along their back are not aberrant or genetic mutations; they are simply older fish.

To date, the Gold Stripe Maroon Clownfish (often simply called GSM in the hobby) is well documented from the Indian Ocean, including Nicobar and Adaman Islands (Example #1 from Nicobar, #2, #3, and #4 from Adaman), as well as Sumatra (Example #1 from Mandas, West Sumatra, Indonesia).

The male counterpart to the female Gold Stripe Maroon shown above. Note the strongly yellow and complete stripes, along with the vibrant color. This fish is perhaps 25% the size of its mate. Image by Matt Pedersen

While there have been reports of “Gold Stripe” Maroons coming from Malaysia, they appear to be completely unfounded. It may simply be that these are “Sumatran” fish, making their way to the US market traveling through Malaysia (a similar story recently happened with “Java” A. leucokranos, which initially puzzled clownfish enthusiasts until it was later revealed that the fish were initially harvested in Irian Jaya, West Papua, and were being sold into the market via Java). As far as I can discern, individuals from Malaysia and Indonesia appear to be representative of the typical “white stripe” Maroon Clownfish. Or do they?

#2. A while back I received a pair of white stripe maroons from a hobbyist, and I noted after the purchase that the female appeared to have yellow coloration in her headstripe. While the pair was supposedly wild-caught, I was hesitant, presuming that they were perhaps a hybrid between the Gold Stripe Maroon and the White Stripe form. Rather than breed them, I ultimately passed them along. Since that time, I’ve discovered that my hybrid concern on that pair was probably completely unwarranted. It appears that Philippine-sourced Maroon Clownfish may have a wider head stripe which can turn gold with maturity.

I brought this observation to Yuri Barros, who in turn also found yellow head stripe fish being observed in Sulawesi and other western areas of Indonesia. It seems occasionally these fish can even demonstrate hints of gold coloration in their midstripes, very rarely their tail stripe. But unlike the true Gold Stripe Maroon Clownfish, in which any fish older than a year of age should exhibit full gold coloration on wide bars, males and younger females of this central geographic group retain white stripes; gold coloration of any level seems primarily restricted to old females. Compare these examples to the GSM pictures above; side-by-side, they are very different.

Could this group represent a another base phenotype within the Maroon complex? In my opinion, this group, encompassing the bulk of Indonesia and the western Pacific, seems to represent a distinctive subgroup within the Premnas biaculeatus species complex, and it is separate from the White Stripes to the east. It would also seem that the original description for the Maroon Clownfish likely came from this regional group, being loosely cited as “East Indies” by Bloch. This group actually well-represents the “White Stripe” Maroon Clownfish generally seen in the aquarium trade, as this is the region that those fish are most often collected from.

A pair of Premnas biaculeatus photographed in Lembeh, Indonesia, clearly showing the gold head stripe on the female in the pair. Image by Silke Baron | Flickr | Creative Commons CC-BY-2.0

Another Indonesian White Stripe Clownfish demonstrates the ability of large females to have gold head stripes; this individual photographed at Gilli Lawa Laut near Komodo, Indonesia. Image by Alexander Vasenin | Wikimedia

Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0

This mature wild P. biaculeatus female was photographed in East Timor. Whether it is an example of an Indonesian-group female that did not develop a gold head stripe, or in fact is part of the next group of White Stripe Maroon Anemonefish, is currently an unanswered question. Determining ranges is an ongoing project; It is a better “fit” with the next group. Image by Nhobgood | Wikimedia | Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0

#3. It seems that the group of White Stripe Maroon Clownfish that inhabit Papua New Guinea (PNG), the Solomon Islands, and the Great Barrier Reef, actually represent a third biogeographic group. Having worked with the PNG group somewhat extensively as part of my Lightning Maroon Clownfish breeding, it always seemed as if there was something unique about PNG Maroons. They didn’t fit precisely with my general concept of what a White Stripe Maroon (often shorthanded WSM) was. Soren Hansen, who also works with PNG-sourced maroons at Sea & Reef Aquaculture, has made similar observances in conversation. We have hunches, and geographical observations are starting to suggest there’s a basis for those hunches.

The bars of these fish appear among the thinnest and most white (refer to the photo above for example); mature females from these locations do not develop the yellow head band. It has been very widely observed that individuals from PNG are prone to aberrant barring, leading to the rise of the “Morse Code” maroon, with many wild examples being exported earlier in this decade. Most recently, a wild “morse code maroon” was exported from the Solomon Islands; observing this phenotype (which we believe has a genetic basis) in the Solomon Islands would further solidify the close relationship between PNG and Solomon Islands Maroons, to the exclusion of the Indonesian White Stripe population to their west.

An example of the typical White Stripe Maroon Clownfish from PNG. As juveniles, this fish would be indistinguishable from their Indonesia / Philippine counterparts, and even at maturity it might be difficult to impossible to know where the fish was from just by looking. Image by Barry Peters | Wikimedia | Creative Commons CC BY 2.0

In addition to the apparent geographic variants of White Stripe Maroons, numerous photos exist showing White Stripe Maroons that have dark-gray stripes; these fish are almost always photographed in the wild, although I have seen similar color darkening in very large old specimens in captivity. This may be a function of age or mood, and not one of geography or genetics. It is interesting though to note that I have not seen this occurring in Gold Stripe Maroons.

Jenny Huang photographed this juvenile Maroon Clownfish showing near-black striping in Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. Why this coloration occurs is not currently known. Wikimedia | Creative Commons CC BY 2.0

Another example of a Maroon Clownfish with dark bars – this one photographed in Komodo, Indonesia. Image by Ilse Reijs and Jan-Noud Hutten | Flickr | CC-BY-2.0

By the same token, all Maroon Clownfish, but particularly the Gold Stripe varieties, are known to lose their stripes as they age. Large individuals with small or absent stripes (even naked) are most probably not genetic mutations, nor should they be confused as geographic variants.

This large Maroon Clownfish of unknown origin demonstrates the ability of Maroons to lose their stripes as they age. Benjamint444 on Wikimedia | CC BY-SA 3.0

Percula Complex

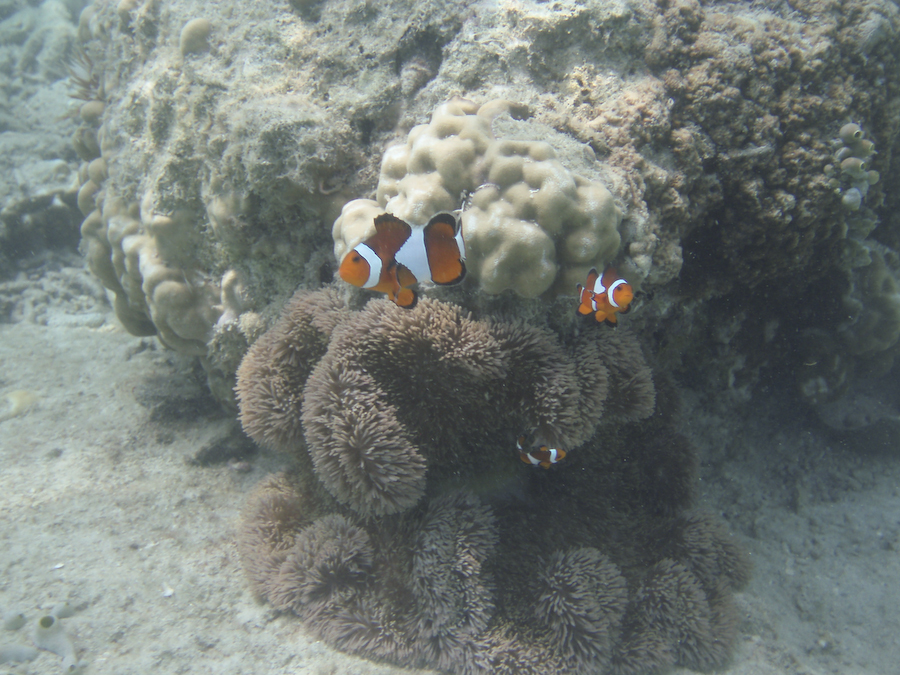

Amphiprion ocellaris – often confused with A. percula, but if you remember that their ranges almost never overlap (there is one claimed location where they might), knowing where your fish was collected can ensure a proper ID.

#1. For the most part, the phenotype of A. ocellaris is rather uniform across its range, showing variations mainly in terms of the darkness of coloration on its back or the weight of the black border colorations. These variations do not appear to be geographically tied, and can be seen in fish collected from the same geographic location. Take a look at these examples of Ocellaris, ranging from east to west.

Amphiprion ocellaris, phtoographed at Moalboal, Cebu, Philippines, by Per Edin | Flickr | CC BY 2.0

Amphiprion ocellaris in Bali, Indonesia, by jeff~ | Flickr | CC BY 2.0

Amphiprion ocellaris, here in the Perhential Islands, Malaysia, documented by Christian Holmér | Flickr | CC BY 2.0

Even further west, now in the Indian Ocean at the Adaman Islands, Amphiprion ocellaris remains unchanged. Image by Sharron Gray | Flickr | CC BY-ND 2.0

#2. Fautin and Allen, 1992, show a slightly more brown variation of the species and cite its location as Sipadan Island, Borneo; Barros also cites these forms in the Malaysian Peninsula including Singapore (such as this one from Singapore). From my perspective, they appear washed out, as if they are simply not getting enough carotenoid pigments in their early diet.

The “brown” form of Amphiprion ocellaris, phtographed here at Terumba Raya, Singapore, by Pel Yan | Flickr | CC BY 2.0

#3. There is also the Black Ocellaris, a solid black fish with white stripes, occurring in Darwin, Australia – I believe this to be a separate species from A. ocellaris requiring further investigation (see prior installment).

The Black Ocellaris from Darwin has been extensively hybridized with the Orange A. ocellaris. Finding genetically pure Black Ocellaris may be impossible in the future unless fresh broodstock from wild sources can be established and lineages kept pure. Image by Matt Pedersen

Amphiprion percula – there is tremendous variation within populations of A. percula that center around the amount of black coloration on the body. Some of the most orange forms can be difficult to differentiate from A. ocellaris.

A. percula photographed on the Great Barrier Reef off Queesnland, Australia, by Paul Arps | Flickr | CC BY 2.0

Virtually every form has been documented in Papua New Guinea (PNG) alone, ranging from solid orange with white stripes bordered by thin black edges, to fish with “black shoulders”, patches of black between the headstripe and midstripe, to full on Onyx forms which have black flanks with white stripes, even black dorsal fins, the orange coloration relegated to the face, fins, and tail.

Amphiprion percula with a fair amount of black on the flanks, photographed in Cenderawasih Bay, West Papua, Indonesia, by ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies | Flickr | CC BY 2.0

The cause for this polymorphism is not well understood, although the late Bill Addison did suggest that Perculas with more black are collected closer to surface waters in the Solomon Islands, a sentiment echoed by others. I mention Percula’s variations here specifically because many have suggested these color forms are geographically linked – in fact, there does not appear to be any substantial geographically-related variation in Amphiprion percula.

If in doubt, check out this video showing three distinct phenotypes (mostly solid orange, a black shouldered individual, and even a wild “Onyx” Percula with nearly-fully black flanks), all living in a couple feet of water, at Munda, Solomon Islands:

Screencapture from the video below, showing wild A. percula in Munda, Solomon Islands, demonstrating polymorphism with three distinct phenotypes all residing in the same shallow water anemone. Video by Youtube user Mkaliner

Here’s another example of A. percula, once again showing varying phenotypes (including a specimen with black spiny dorsal) in video taken near Veura Village, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands.

Genetics | Hybrids | Species Part 1| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6a | 6b | 6c | 6d | 6e | 7 | 8 | Index

Photo Credits – all photos as credited in their captions.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks