The reefs at Palmyra Atoll, a small outlying atoll in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, have been undergoing a shift from stony corals to systems dominated by corallimorphs; marine invertebrates that share traits with both anemones and hard corals. In a newly published study led by the University of Hawai‘i (UH) at Mānoa, marine biology researchers discovered that although the invading corallimorph is the same species that has been there for decades, its appearance recently changed and it became much more insidious.

Phase shifts such as this are being seen in many marine environments globally—whether due to local pollution, global climate change, or natural environmental variation. Researchers from the UH Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST) wanted to determine if a new species of corallimorph was responsible for the takeover in Palmyra.

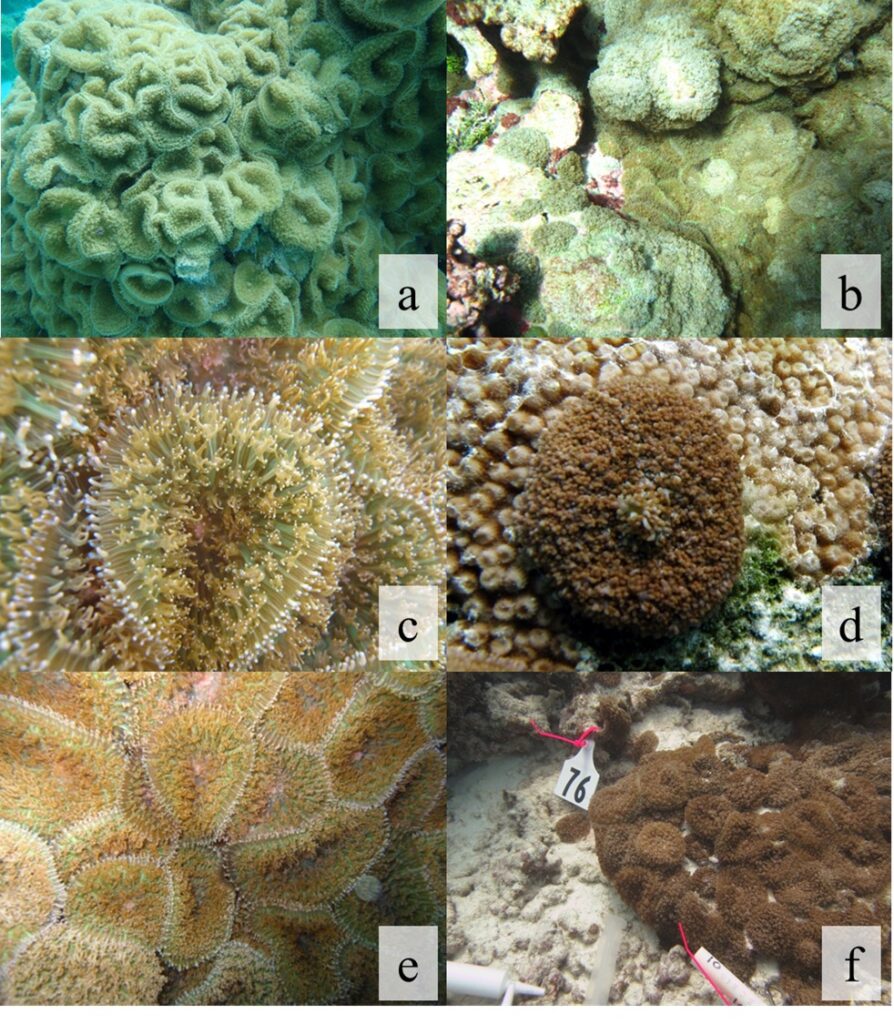

“These phase shifts are negative to our overall biodiversity,” said Kaitlyn Jacobs, lead author of the study and graduate student at the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) in SOEST. “In the last decade, Palmyra’s nearshore reefs have been invaded by corallimorph colonies that can rapidly monopolize the seafloor and reach 100 percent cover in some areas.”

Jacobs and her team used DNA data to compare the mitochondrial genomes of four corallimorph individuals collected from Palmyra Atoll. They discovered that the corallimorph that was outcompeting surrounding corals is not a new species but rather is most closely related to a species from Okinawa, Japan.

The Palmyra Atoll National Wildlife Refuge was created in 2001 and has been protected ever since. The atoll has been characterized as a nearly pristine coral reef ecosystem—supporting a highly productive ecosystem and high levels of coral cover.

Because of their adaptability, corallimorphs are excellent competitors. In addition to being able to kill corals directly, they can quickly move into disturbed areas and out-compete surrounding organisms, creating a sort of blanket on the reef.

“There is concern among scientists and conservationists that the phase shift from stony coral-dominated habitats may be irreversible due to a negative feedback loop of coral decline and subsequent algal, sponge, or corallimorph domination,” said Jacobs.

Biodiversity is extremely important for the health of any ecosystem—each organism has a role.

“So if we can better understand these shifts at the genomic level it can better help resource managers deal with large outbreaks effectively,” said Jacobs.

Credit: From materials released by the University of Hawai’i at Manoa.

ABSTRACT

The reefs at Palmyra Atoll, a small outlying atoll in the equatorial Pacific, have been undergoing a phase shift from scleractinian corals to a corallimorph-dominated benthos. It has been unclear whether there has been cryptic speciation or morphological plasticity leading to different ecotypes of Rhodactis howesii. Here, we use mitochondrial genomic analysis to assess species validation and underlying cause of morphological variation across the atoll. We mapped sequenced reads to Rhodactis indosinensis, R. howesii’s closest recorded genomic taxon. In addition to one individual from American Sāmoa, we assessed phylogenetic relationships of published corallimorph genomes with those from Palmyra. There was no identifiable population structure within Palmyra, and available dinoflagellate symbiont communities were consistent among the sequenced individuals. There were noticeable differences in symbiont communities between Palmyra and American Sāmoa individuals, as well as six fixed nucleotide differences. We conclude that the lack of taxonomically validated genetic reference material together with vague species descriptions, morphological plasticity, and overlap among morphological characters, combine to raise doubts about the validity of the currently accepted species name, R. howesii. Comparison of our results to all currently available genetic data for corallimorpharians suggests that the species at Palmyra is most closely related to an unidentified species of Rhodactis from Okinawa. However, taxonomically confirmed R. howesii is absent from genetic databases, so no firm conclusions about species identification can yet be drawn. It seems clear that this group is in need of additional taxonomic work and a broad phylogenetic survey of taxa with geographic distribution would further our understanding of marine biodiversity, conservation, and invasion dynamics of this understudied group.

REFERENCE

Jacobs, K.P., Hunter, C.L., Forsman, Z.H. et al. A phylogenomic examination of Palmyra Atoll’s corallimorpharian invader. Coral Reefs (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-021-02143-5