A thriving “safe place” can be a major enhancement to any captive reef system

Text & art by Daniel Knop

Excerpt from CORAL, May/June 2020, Reefkeeping 101

Refugia are vital components of natural coral reef ecosystems. Many creatures rely on a safe place to retreat to, a place where they can find protection from predators, pounding surf, and overwhelming currents. Refugia can also be provided in a reef aquarium system, and for some species a designated refugium space is necessary.

For coral reefs in nature, the mangrove zone is the classic refugium. Innumerable larvae and other juvenile stages of numerous marine fishes and invertebrates gather there in the complex network of stilt roots, which bar entry to larger predators and provide calm water conditions. They wouldn’t survive long on the coral reef or in the open ocean, where they would be surrounded on all sides by hungry mouths. Other places that provide shelter are seagrass beds, rubble zones, and sheltered niches within the hard substrates of the reef.

The general definition of the term “refugium” in an aquarium system is a separate place, usually a tank or chamber, which is created specifically as a safe haven for macroalgae and tiny invertebrates, and sometimes a few small fishes. This begs the important question: There are many examples of successful aquariums without a refugium, so why bother with one for a reef system?

Shrimp-like amphipods in the suborder Gammaridea proliferate very rapidly in the substrate of every refugium.

Microfauna breeding ground

The function of a refugium offers one thing above all: space to multiply, either for macroalgae or myriad small marine invertebrates to grow and reproduce. The algae, if not continually grazed down by fishes, can absorb significant quantities of nutrients, primarily nitrates and phosphates, while teeming invertebrate life produces eggs and larvae continuously, providing a source of planktonic food for corals and reef fishes. This is an important component of the community on the natural reef: reproduction in many groups of aquatic animals generates a huge excess of offspring, and the vast majority of the eggs and larvae are destined to fall prey to other creatures (or, to put it bluntly, serve them as food).

Copepod larvae are a good example of the microplankton that may be found in the established reef aquarium. These larvae can evade aquarists’ notice because they are too small to be seen with the naked eye. In the sea they form the bulk of the zooplankton and are a fundamental component of the food chain. In a captive system, copepods require a refugium in order to reproduce prolifically, but the great majority of reef aquariums don’t provide this food source, which is nutritionally valuable for many corals. Copepods are just one of the many possible examples of tiny planktonic organisms that are available to corals in their natural habitat but not in the majority of aquariums.

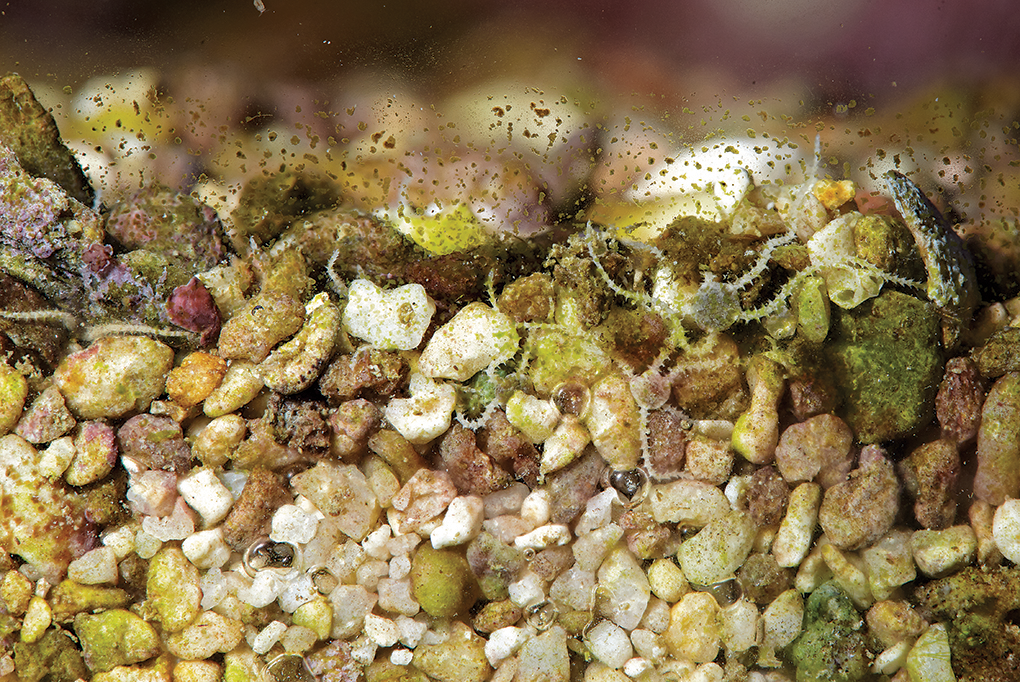

A profusion of organisms that have colonized the rubble over a period of years in one of the author’s refugia.

Among the small invertebrates that can populate productive refugia are amphipods, tanaids, ostracods, bristleworms, tube worms of many types, brittlestars, sponges, sea squirts, and various gastropods or snails. Some cnidarians that tend to appear in a refugium can be an annoyance for aquarists, particularly the dreaded Aiptasia. Countermeasures are necessary if Aiptasia appear in the refugium, because, owing to severe predation pressure in the natural habitat, they have developed the ability to proliferate so rampantly that, without losses to predation, they become dominant invaders that take over the habitat in short order. This is most easily prevented by introducing a small group of Peppermint Shrimps (Lysmata wurdemanni) or other related species. These larger crustaceans regularly produce larvae, which, when washed back into the display tank, provide a rich meal for corals and fishes.

Promoting microfauna in the refugium

What can we do to promote the development of the microfauna in the refugium so that lots of planktonic larvae are produced? A number of things are required. First, there should be a reasonable depth of bottom sediment—1.5 inches (4 cm) of fine coral sand (aragonite) is a good minimum amount. There should be water movement above the bottom sediment—not turbulent, but as uniform and laminar as possible. Turbulence is undesirable, as it would stir up and rearrange the sediment. The sediment may need to be loosened at regular intervals so that it doesn’t become too densely clogged with fine sediment and develop oxygen-depleted areas where the inhabitants can no longer survive. This is possible through manual maintenance but can be supported by introducing burrowing creatures (e.g. bottom-dwelling snails, small sea stars, or other echinoderms).

It is helpful to “inoculate” a refugium by occasionally introducing highly porous, freshly-imported live rock, reef rubble from the sea, or good live sand, so that the invertebrates and bacteria from it can arrive there without being eliminated by predation. Cultures of amphipods, copepods, spaghetti worms, and many other appropriate fauna are also available and will be covered in a future article in CORAL.

Bristleworms are often hitchhikers on live rock, and are considered beneficial in almost all cases, living mostly hidden and scavenging in the bottom of the refugium.

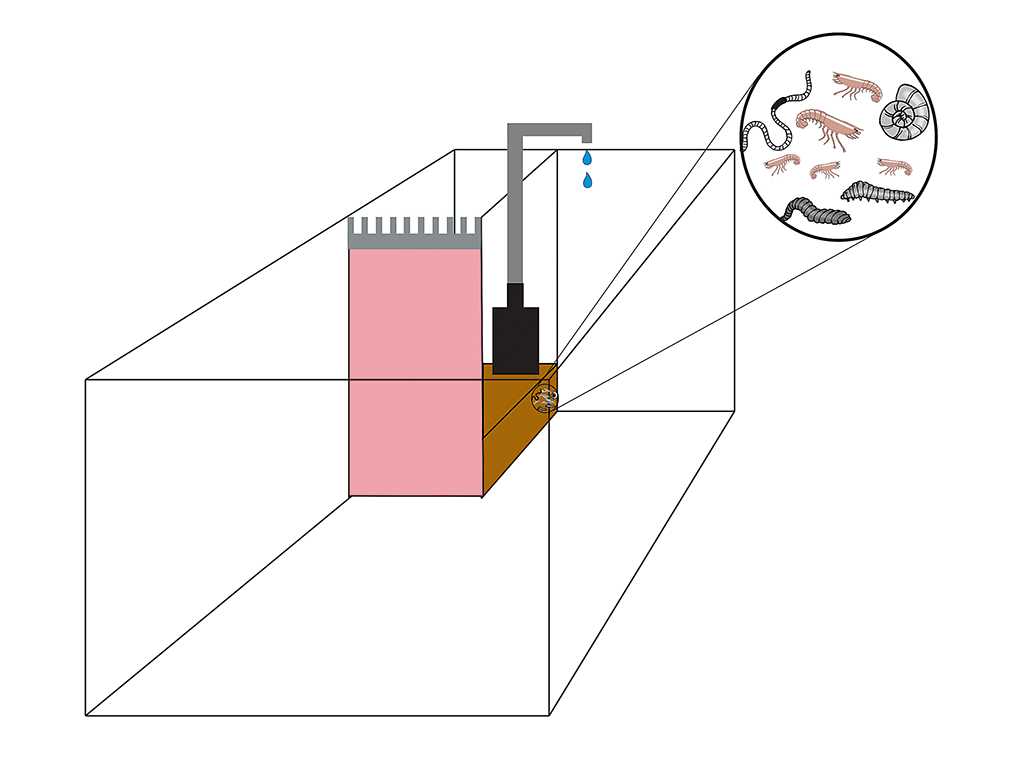

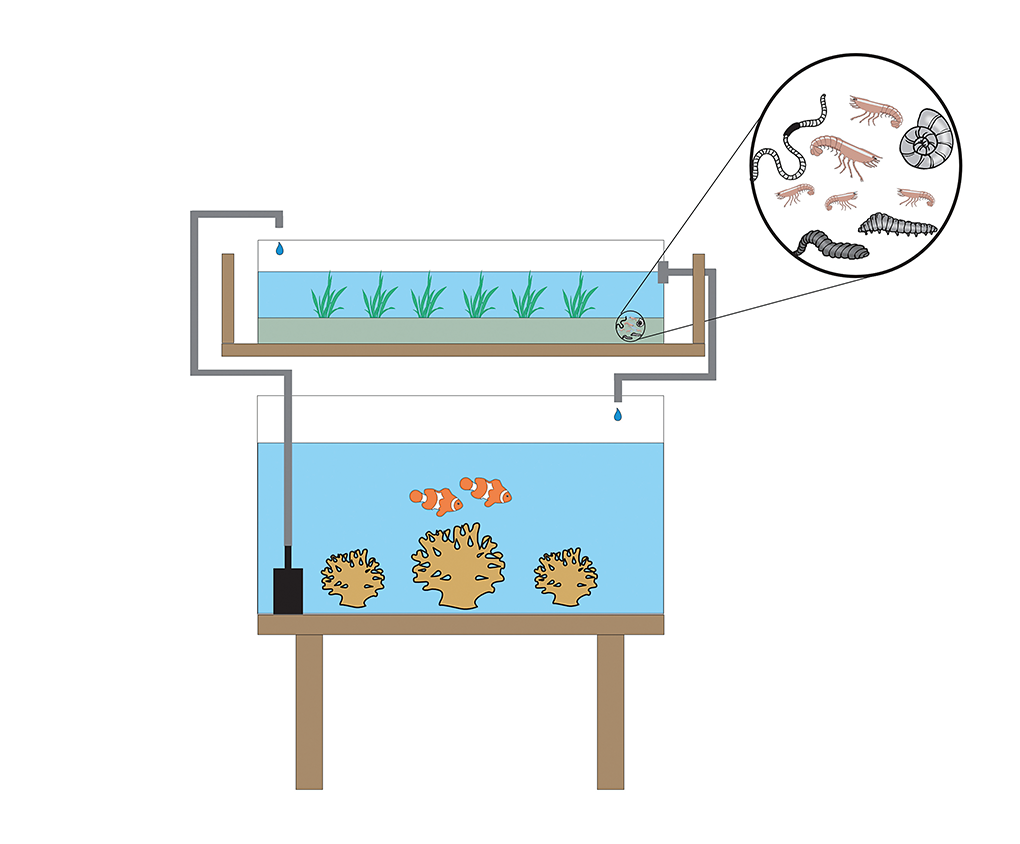

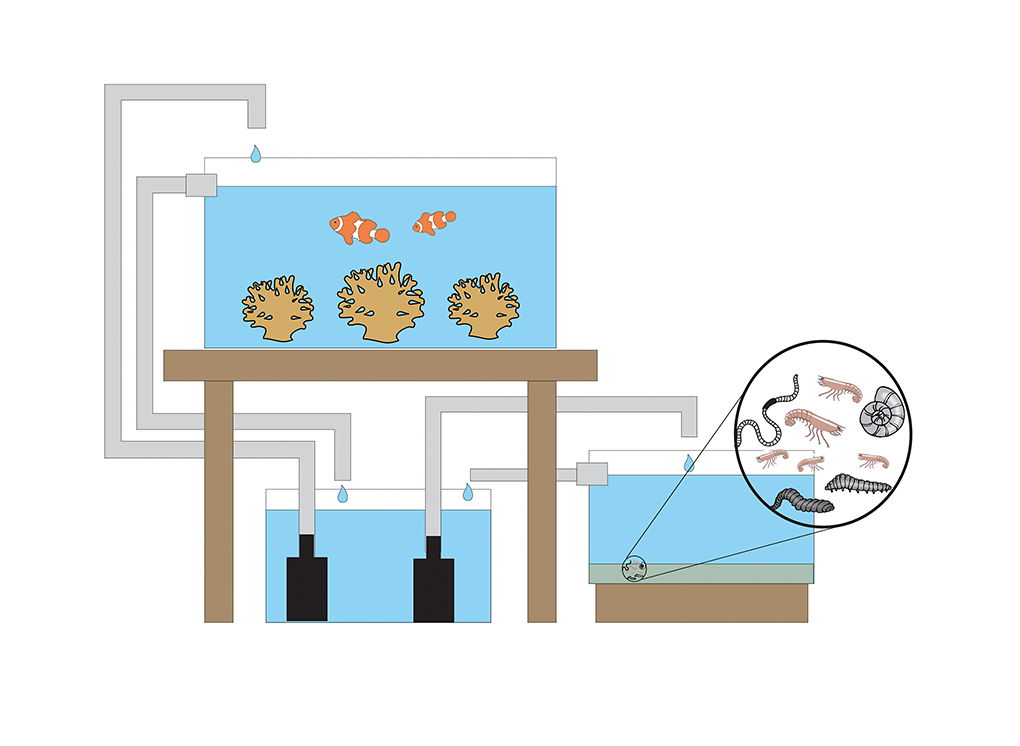

Some aquarists like the option of having a refugium supplied with incoming aquarium water that does not have to pass through filter and/or skimmer beforehand, thus allowing uneaten food to wash in and feed the refugium. Many plumbing configurations are possible, but you should make sure to orient the water stream so that larvae arrive in the aquarium directly from the refugium, without having to pass through the filter or skimmer (see diagrams.) This requires that the refugium is operated separately and not as part of the sump, where you would install the water treatment (particulate filter/skimmer/reactors). Most equipment should be kept out of a refugium, as it will become contaminated with detritus and colonized by worms or encrusting organisms.

If the refugium is provided with full-spectrum illumination, it can support the rampant growth of many types of macroalgae, most often Spaghetti Algae (Chaetomorpha sp.), Sea Lettuce (Ulva lactuca), Caulerpa spp., or Red Bush Algae (Gracilaria sp.). Some reefkeepers run their refugium lighting on an opposite schedule of that of the display tank so that the macroalgae is engaged in photosynthesis during the main aquarium’s nighttime hours, absorbing CO2, stabilizing pH, and producing oxygen.

A separate refugium is ideal, as it receives water unfiltered and also returns it to the display tank unfiltered after passing through.

Acclimation sanctuary

An additional benefit to having a refugium is that new livestock acquisitions that are difficult to acclimatize in the presence of resource competitors can be allowed to settle in quietly in a safe refuge. During the first few weeks, trophic specialists will find a much richer microfauna there than in the reef aquarium itself and can gradually become accustomed to frozen or dry food that is target-fed to them. Without stress from competitors for food or space, they can get used to the water conditions and the biochemical traces of all the aquarium inhabitants, and the fishes in the main tank will become aware of the presence of the newcomer in the refugium. Likewise, a habituation effect can reduce subsequent confrontations.

Research has shown that newcomers to an established reef fish community are far less violently attacked if they have previously spent several weeks elsewhere in the aquarium system. During this isolation these newcomers will feel less stress in a refugium with live rock and some macroalgae than in an empty filter chamber containing nothing but seawater. The microfauna of the refugium will decrease significantly during this time but will recover after the newcomer is moved to the main tank. During this phase it is no longer a refugium for very small invertebrates, but one for the newcomer.

The tiny Amphipholis squamata brittle star usually multiplies rapidly in the substrate of a refugium. Both the adults and larvae of such benthic invertebrates can be excellent foods when carried back into the display aquarium.

End Notes

There is one fundamental point regarding refugia that must always be taken into consideration: when adding calcium, carbonate, and amino acid solutions as well as trace-element concentrates, these should not be dosed into the refugium, but rather into one of the other sump chambers (preferably the final one) or directly into the aquarium, in order to avoid heavy consumption within the refugium.

It is undisputed that refugia offer many advantages to the aquarium system. These include, above all, enlarging the water volume, increasing the biodiversity (in particular that of microorganisms and small creatures), breaking down or exporting waste nutrients (nitrate and phosphate), stabilizing the pH and oxygen concentration, and expanding the food supply for fishes and corals via the production of numerous larvae that are washed into the aquarium. A thriving refugium can be a major enhancement to a captive reef system, while also expanding the husbandry experiences of the reefkeeper.

Caulerpa spp. thrive in refugia but can release growth-inhibiting substances that inhibit coral growth. Many reefkeepers today prefer Ulva (Sea Lettuce) or Chaetomorpha (Spaghetti) as macroalgae in the refugium.