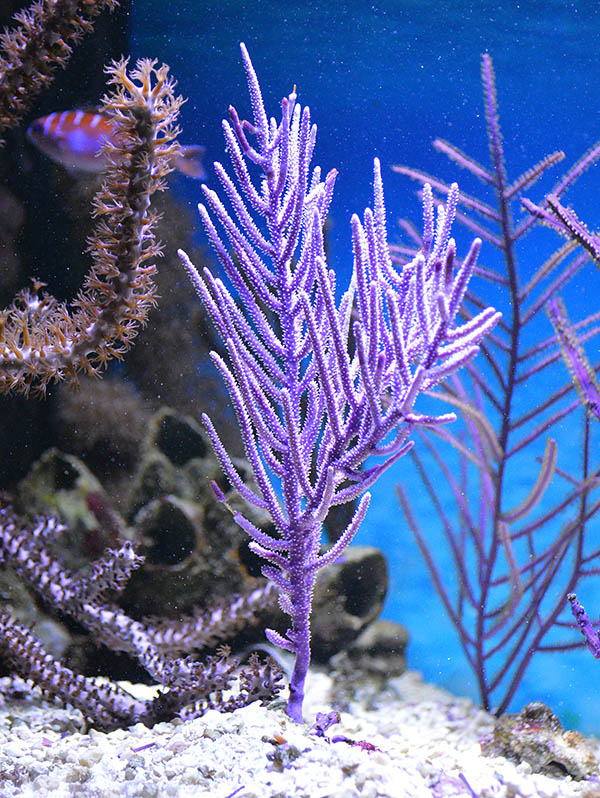

A Florida Keys biotope: the modern reefscape is dominated by numerous photosynthetic octocorals we commonly refer to as gorgonians. Several distinct species are clearly visible in this recent photo, taken during a collecting trip by Florida aquarium trade collector Philipp Rauch of KP Aquatics.

By Matt Pedersen

Image Credits – Matt Pedersen with Mike Doty, unless otherwise noted

I realized several years ago that the United States’ marine aquarium hobby seemed to have moved on from its local roots.

Case in point: some of you may be familiar with tales of the luminous Beau Gregory (Stegastes leucostictus). They were once a staple of the marine aquarium hobby, but when is the last time you saw one of these glorious (but vicious) damselfishes for sale in your local fish shop?

Such a stunner, but never really in the aquarium trade these days: The Beau Gregory, Stegastes leucostictus, a juvenile, photographed near a small patch reef just west of Cut Cay, eastern Graham’s Harbour, northeastern San Salvador Island, eastern Bahamas. Image Credit: James St. John, CC BY 2.0.

I grew up reading the tales of Florida’s Robert P.L. Straughan, whose book, The Salt-Water Aquarium in the Home, was routinely checked out (by me) from my local library. Straughan, a true pioneer of the marine aquarium hobby in every sense of the word, was on the Florida reef frontier, collecting fishes and corals in our local continental subtropical waters and bringing the ocean to the homes of people around the country. He literally wrote the guidebooks for becoming a marine-life collector in Florida (The Marine Collector’s Guide and Adventures in Marine Collecting are both cherished used-book finds now gracing my shelves, exciting reads worthy of your attention).

Straughan has long since passed away, as have probably most of those who personally knew him, along with probably two more generations of collectors between then and now. But Florida’s marine aquarium fishery persists to this day, evolving and responding to a changing environment along the way. In my lifetime, I’ve come to know a handful of Florida’s collectors personally; a couple have now retired, but the contemporary generation of younger collectors continues to find a way to have a business and raise a family in one of the most unique occupations one could dream of, diving to fish in the wild ocean, day in and day out.

Meet the Family

Born in Kaufering, Bavaria, Germany, in 1985, Philipp Rauch no more knew his destiny than a tea leaf knows the history of the East India Company. Rauch had his sights set on the automotive industry for a career, studying automotive management and working as an apprentice in dealers, both in sales and car repairs. He traveled to the U.S. to obtain a bachelor’s in business administration at the West Palm Beach campus of Northwood University, where he met his future wife, Kara Nedimyer.

Some aquarists may recognize the Nedimyer family name; Kara is the daughter of Ken Nedimyer, the Florida fish collector who operated the live rock farm and marine life collection business Sea Life, Inc. and founded the now widely known Coral Restoration Foundation (CRF). While some kids get summer jobs mowing laws or working at a fast food restaurant, Kara grew up learning how to collect alongside her father, starting at the age of 10.

Kara and Philipp Rauch diving on location at the KP Aquatics Live Rock farm off the Florida Keys. Image courtesy KP Aquatics.

Rauch went on his first dive with Kara at the family live rock farm in 2004 to help dig up rock after a storm. He decided to get dive certified 3-4 months later, and so began his hands-on learning of the Nedimyer family business. As Ken moved on to focus on CRF, Kara opted to take over the family business in 2010. Philipp moved to the U.S. permanently, married Kara, and together they rebranded the family business as KP Aquatics in 2011. Asked why he left the automotive field for the seemingly unrelated world of diving to collect marine ornamental fish and livestock, Rauch admits being drawn to the entrepreneurial aspects of his wife’s family business.

Philipp and Kara Rauch, proprietors of KP Aquatics, one of a very limited number of Florida marine life collectors responsible for bringing our native tropical marine fish and corals into the aquarium trade. Image courtesy Lois Hatcher.

These days, Philipp Rauch is the main collector and the face of KP Aquatics. While Kara does join Philipp in the water at times, she is also busy raising the family’s two children and serving as the treasurer for the Florida Marine Life Association (FMLA).

Membership in the FMLA is voluntary for marine fish collectors in Florida. It is unique because the FMLA was formed specifically to ask the state of Florida to regulate the state’s marine aquarium fishery. Regulations, such as the closure of collections for Condylactis anemones and limits and size restrictions for angelfish species, and regulations for snails and Ricordea, are all the result of the collaboration between state agencies and the FMLA.

As Rauch sees it, the FMLA has set out to create a long-term, generational fishery, and with that comes the reality that Florida’s marine aquarium fishery has very limited entry, with a capped number of fishermen. At this time, Rauch suggests that if you can find someone willing to sell their transferable license, it will cost somewhere in the range of $20,000 to $40,000 just for the license to collect.

Gorgonians – A Florida Staple

KP Aquatics offers a wide range of marine aquarium life to wholesalers and retailers, and sells direct to the public. In an era where wild-harvested live rock supplies are dwindling or being eliminated and sterile dry rock seems to have been the default replacement, Rauch emphasizes the family’s live rock farm as one of the most important items they produce; he believes it is key to the company’s future. While fish and inverts are certainly routine offerings, they are more labor-intensive to collect; alongside the farmed live rock, it’s zoanthids, ricordeas, and gorgonians that are the bread and butter of KP Aquatics.

At this point, you’d have to have your head buried in the coral rubble to not know that Florida’s “coral reefs” have by and large given way to the rise of a gorgonian-dominated seascape. Of course, these graceful soft corals were always present, but stony corals, particularly Acropora, are noteworthy these days for their relative absence. Aquarists can currently only dream of a well-rounded Florida biotope tank (with enough space, I suppose the off-limits, endangered A. palmata and A. cervicornis could be really interesting in an aquarium).

Still, Florida’s native gorgonians offer a dizzying array of growth forms in a subtle color palette that every aquarist should come to know and appreciate. Being “local,” they’re affordable and relatively easy to find. Rauch says that many varieties are quite plentiful in the wild, and in his view, their harvest is entirely sustainable. Most are photosynthetic, and once they’ve survived the initial acclimation to home aquarium life, they can grow and be propagated with relative ease.

Meet Florida’s Gorgonians

We approached Philipp Rauch with a simple task – give us your perspective on the gorgonians you collect for marine aquarists. This can be a daunting task; Nova Southeastern University documents 47 unique species of octocorals in southern Florida. Conversely, KP Aquatics offers only 14 distinct varieties, and most references refuse to identify the bulk of Florida’s gorgonians beyond the genus level.

When asked why KP Aquatics doesn’t offer a wider selection of the species, Rauch noted that he only targets the species that tolerate shipping well and adapt to aquarium life, ensuring happy customers and long-term success. For example, the Slimy Sea Plume, Antillogorgia americana, is easy to find and may actually do well in the home aquarium, but it is a very poor shipper, so Rauch leaves it in the ocean.

Rauch noted that while Florida’s collectors are well organized under the FMLA, when it comes to sharing information there is still a healthy level of trade secrets involved. Collection spots are well-guarded secrets, and misinformation shouldn’t be a surprise; for example, a collector might suggest that they’re finding something at 110 feet, when in reality it exists in waters only 70 feet deep. Rauch even joked (but maybe was a little serious and apprehensive) when he suggested that after we published this article, all our readers would just show up and start collecting their own gorgonians. I suppose, in the end, whether you’re a trout angler who obfuscates the background in all his fish photos and never reveals stream names, or you’re a veteran marine fish and coral diver, we’re all fishermen and we’re all guilty of the same friendly game of secrecy and one-upmanship!

Florida’s Nonphotosynethic Gorgonians (NPS)

Collectors ply Florida’s waters for three varieties of azooxanthellate gorgonians, which are found in deep water. All require dim lighting to prevent the growth of nuisance algae on their surfaces, and all require deliberate, intentional feeding in order to survive in the home aquarium. As a result of their demanding cultural requirements, despite their often inexpensive pricing, they are generally regarded as “expert-only” animals not suited for inexperienced aquarists.

That said, improvements in coral feed and a wide range of nutrient export options may result in longer captive lifespans than history would suggest. Frankly, the success of my own 1.25-gallon “vase reef” has me wondering if the weekly 100% water changes could work well to mitigate the pollution problems often associated with NPS corals and their high feeding demands.

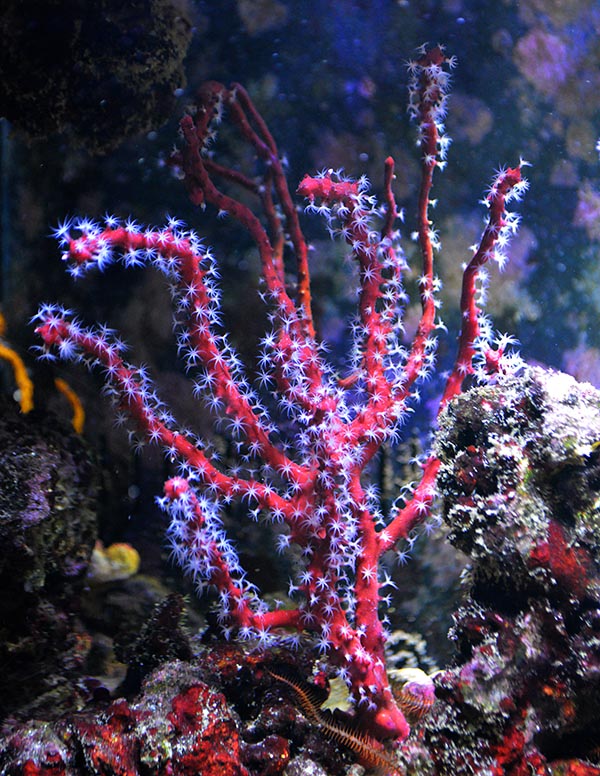

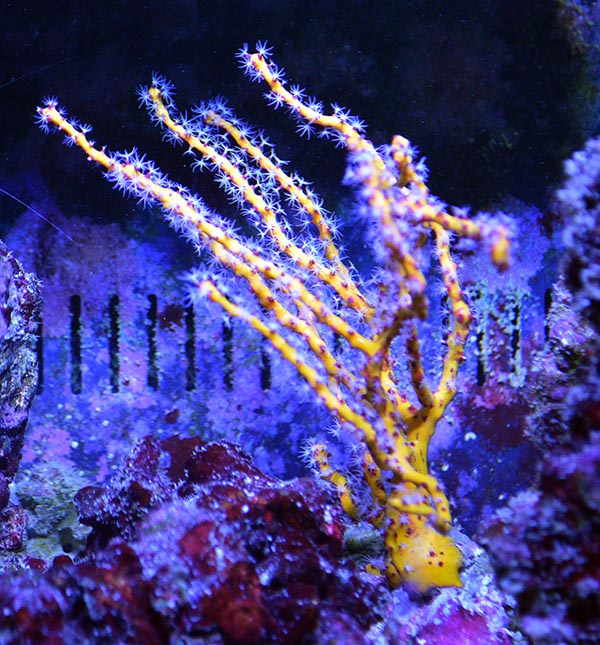

The Finger Gorgonian, Diodogorgia nodulifera: This species of gorgonian is so brightly colored that at first, aquarists might not presume it even originates from Florida’s waters. Even more surprising is the reality that there are two distinct color forms found within this species: a beautiful red form and a bold yellow form that has red highlights; both forms have snow white polyps. Collectively, these forms are traded under a wide variety of names, including Yellow/Red Sea Rod and Yellow/Red Tree Gorgonian. They seem to reach a maximum size of 12 inches in height.

The Red Finger Gorgonian, Diodogorgia nodulifera, a stunning but often challenging species to maintain.

Rauch noted that this is a gorgonian they do not directly collect, but instead purchase from a fellow collector working further north along Florida’s main Atlantic coast in waters at depths of 100 feet. In general, he cited 70 feet as the transition point between photosynthetic and nonphotosynthetic gorgonians in Florida’s waters.

The Yellow Finger Gorgonian is also considered to be Diodogorgia nodulifera, and despite the difference of color, it requires the same specific flow patterns and heavy feeding if it will have a chance at long-term survival in the aquarium.

The Orange Tree Gorgonian, Swiftia exserta (not shown), is the other NPS gorgonian routinely collected from Florida’s waters, and some might argue it’s the most attractive of the three, with an orange body and red polyps. This species can reach impressive sizes and tends to grow in a “sea fan” shape, suggesting that it might benefit from directional, laminar flow and would best be oriented perpendicular to that flow to maintain the proper growth from (as is required with other sea fans).

Florida’s Photosynthetic Gorgonians

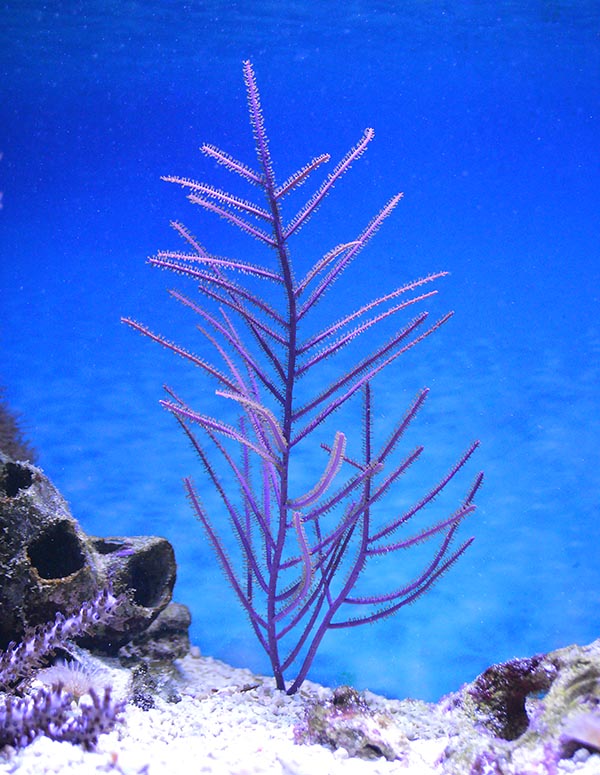

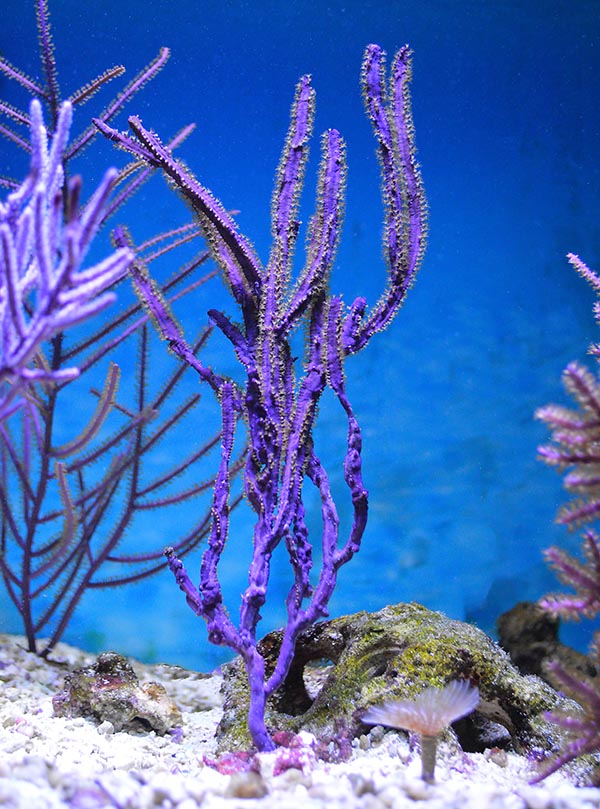

Bipinnate Sea Plume, Antillogorgia bipinnata and Purple Frilly Gorgonian, A. acerosa

The experts disagree as to whether this shallow-water, purple, feather-like gorgonian is Atillogorgia acerosa or A. bipinnata. Regardless, these are generally hardy gorgonians capable of reaching impressive sizes.

Purple, feather-like Gorgonians are typical of what many think of when it comes to Florida’s photosynthetic gorgonians. However, their identification can be difficult. In fact, this first example has been identified as both Antillogorgia bipinnata and A. acerosa, depending on who we asked!

Formerly considered to be in the genus Pseudopterogorgia, collectively these species are also known as the Purple/Yellow Bipinnate, Purple/Yellow Willow, Purple/Yellow Frilly, Common Sea Plume, and the Purple/Yellow Feather Gorgonian. The Slimy Sea Plume (A. americana) is also similar, and the two could be confused. It is well documented that both A. bipinnata and A. acerosa range in coloration from coveted purple forms to more mundane golden-yellow or tan varieties.

Rauch primarily collects the purple forms, which are more common in the northern Florida Keys, and he noted that the yellow form is more common further south in the Keys. Both color forms Rauch targets are found closer to shore in shallow water down to 25 feet (7.5 m), but in higher densities at depths of 10-15 feet (3-5 m). Both species can grow quite large, reportedly reaching heights of up to 5-6.5 feet (1.5 -2 m), but are usually 3 feet (1 m) or less. Both species tend to grown on a vertical plane, blade-like, with long branches arising from a single main stem and polyps only on the edges of the rods. While we cannot pin down which species Rauch is personally collecting, both species are suggested to be hardy and robust species that tend to do well in aquariums. The specimens offered by Rauch are typically between 6 and 12” in size, and may not be entire gorgonians but instead are sometimes frags snipped off and harvested from a larger specimen on the reef.

Purple Sea Feather, Antillogorgia elisabethae

A little more “compact” and “fuller,” Antillogorgia elisabethae originates from deeper water and might require less light, although other husbandry requirements suggest this species should not be your first Floridian photosynthetic gorgonian.

Among several “purple,” “feathery” gorgonians originating from Florida, this species can most likely be confused with the Purple Plume Gorgonian (Muriceopsis flavida), but upon closer examination with a trained eye, they become easy to distinguish; A. elisabethae has branches that are flat/oval in cross section with polyps on the edges, whereas M. flavida is round with polyps on all sides. These two species also live in completely disparate habitats.

Rauch typically finds A. elisabethae in deeper water ranging from 40-60 feet (12-18 m), although the species is known to range anywhere from 6 to 100 feet (2-30 m). Rauch notes that it is more abundant in the northern Keys, and he shared that that this species (and the Corky Sea Finger) took a bit of a beating from Hurricane Irma, although their populations are now recovering.

The Purple Sea Feather is a more challenging gorgonian species; it does not ship as well as other relatives and so is generally packed individually. This species does not readily tolerate physical contact, particularly touching other gorgonians, so care must be taken to give it adequate room on all sides. Overall, while it is still a photosynthetic gorgonian, Rauch feels this species is a moderate to advanced species to care for, and thus wouldn’t eagerly recommend it as your first gorgonian.

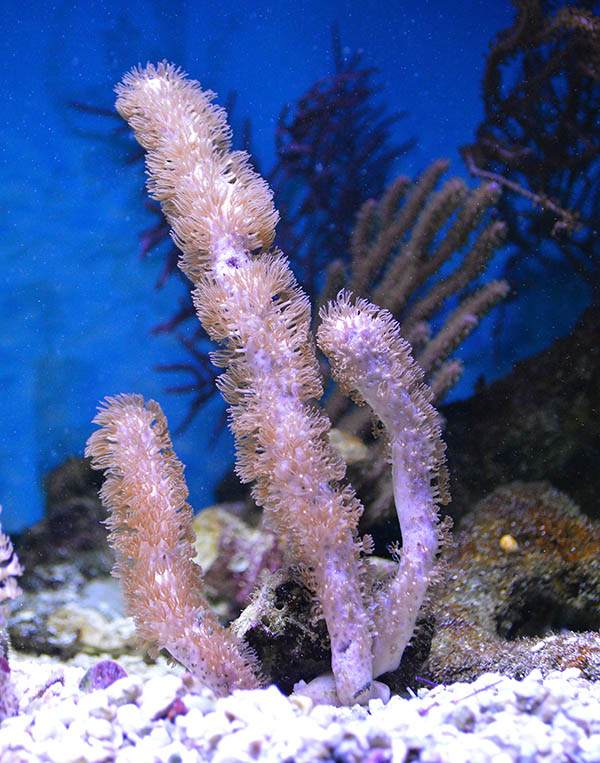

Corky Sea Fingers, Briareum asbestinum

Truly thick upright fingers make Corky Sea Fingers, Briareum asbestinum, somewhat unique among its counterparts. Widely regarded as an easy-to-keep coral, ideal for beginners.

Also known as Dead Man’s Fingers, B. asbestinum specimens with purplish bases are the most coveted. While they are widespread on Florida’s shallow reefs, Rauch targets specimens found along the edges of reefs at depths of approximately 40 feet, which tend to grow as fingers and spires on hard substrates. These corals are widely regarded as hardy corals ideal for beginners.

In addition to B. asbestinum, there are two other related species found in FL waters that could be confused with B. abestinum: the Climbing Knobby Sea Mat (B. polyanthes), which is somewhat similar, although it typically grows over other gorgonians rather than forming its own vertical fingers; and the Encrusting Gorgonian (Erythropodium caribaeorum), which usually grows as a mat and has small polyps.

Knobby Sea Rod, Eunicea cf. calyculata

This single-rod specimen of Knobby Sea Rod, tentatively identified as Eunicea cf. calyculata, will branch out as it grows.

There are currently 15 species of Eunicea gorgonians in Florida’s waters, many of which are similar in appearance, making a positive species identification very difficult. The form collected and sold in the aquarium trade as Knobby Sea Rod may also be known as Warty Sea Rod, and may be the species E. calyculata.

Rauch reported that it is probably the most common species, found all over the place at depths from 10 to 50 feet (3-15 m). It is typically collected as a small 6-8-inch single spire, but it branches as it grows. It is generally regarded as being quite hardy, and it grows so well that it may require regular pruning in the aquarium. It’s worth noting that slit-pore gorgonians of the genus Plexaurella are sometimes collected and shipped alongside Eunicea spp. in the aquarium trade; these are generally equally hardy and great aquarium candidates as well.

Purple Sea Rod, Eunicea flexuosa, and Black Sea Rod, Plexaura homomalla

The striking Purple Sea Rod, Eunicea flexuosa, is thicker in diameter than most other purple gorgonian species collected in Florida. It is a bit more sensitive but rewards the aquarist with a beautiful candelabra form. The similar Black Sea Rod shares the same form but has a blackish-base coloration in the best specimens.

Purple Sea Rod and Black Sea Rod (not shown) share similar candelabra growth forms and outward appearances and may be found together on the reefs. Both used to be considered members of the genus Plexaura, although the Purple Sea Rod has apparently been moved to the genus Eunicea.

Rauch says he typically finds Purple Sea Rod in large numbers at the reef edge, not alongside other purple whip-type gorgonians, at depths of 25 feet (7.5 m). The Black Sea Rod, also known as the Golden Sea Rod, used to be abundant in the upper Keys, but the cold snap in 2010 has set this species back; these days he typically finds them growing alongside Ricordea at depths of 20-30 feet (6-9 m). Both species of sea rods are more sensitive than other gorgonians, are best shipped at smaller sizes, and are less forgiving of poor water quality. Though they are among the most visually stunning of Florida’s gorgonians, Rauch only recommends them to more experienced aquarists.

Rusty Gorgonian, Muricea elongata

Also known as the Spiny Orange Gorgonian, Rauch reports that M. elongata tends to be found closer to shore on patch reefs in 20-25 feet of water, often alongside Knobby Sea Rods (E. cf. calyculata) and the Slimy Gorgonian (A. americana); the species’ depth range is regarded as approximately 10 to 70 feet (3-22 m). It is a variable species; Rauch notes that the brighter orange specimens are found in shallow water, and that a more beige variation is not collected very often. Overall, the Rusty Gorgonian is considered to be on the hardy side and is recommended as a good candidate for a first gorgonian.

Rough Sea Plume, Muriceopsis flavida

Muriceopsis flavida is readily distinguished from other purple gorgonian varieties when you note that the branches form on all sides, and the individual polyps are also distributed entirely around the cylindrical branches.

Also known in the trade as the Purple Brush or Purple Plume Gorgonian, at smaller sizes it may be confused with the Purple Sea Feather (Antillogorgia elisabethae). M. flavida has round branches that grow on all sides of the main stem. It’s a slightly smaller species, maxing out at 2.5 feet (0.75 m) in height, and is usually sold much smaller. Rauch notes that this species is not as common as some others, but is still generally abundant and collected most often 1.5-3 miles offshore in 15-25 feet of water. Care-wise, he considers these “middle of the road,” still acceptable for first-time gorgonian-keepers but not quite as hardy and resilient as some of the others.

Angular Sea Whip, Pterogorgia anceps

Wide, flat blades are the reason that Pterogorgia anceps is often called the Purple Ribbon Gorgonian.

While one could hypothetically lump this into one of several purple gorgonians that originated from the Florida Keys, this species is truly unmistakable in appearance. It is also known as the Purple Ribbon Gorgonian and Purple Sea Blade, owing to the very broad, flat purple branches adorned with brown polyps only on the edges. Rauch suggests that you’ll find this species all over the reef; at depths off 20 feet (6 m) or more they can appear grey or yellow, but in the shallows—5 to 10 feet (1.5-3 m)—they are vividly purple. The maximum size for this species is just under 2 feet in height (0.6 m). Given their shallow origins, strong light and strong wave-type currents are ideal for their husbandry. As Rauch puts it, “They are very pretty, super hardy, almost foolproof. They can go anywhere and do fine.”

Yellow Sea Whip, Pterogorgia citrina

Rauch believes that if an aquarist wants a super-hardy gorgonian, this species and its preceding relative are the ideal candidates. This species carries many common names, including Yellow Ribbon, Gold Ribbon, and Green Lace Gorgonian. The smallest of all the gorgonian species covered here, it tends to grow more wide than tall. It is found in shallow areas, typically at a depth of 3 to 33 feet (1-10 m); the specimens Rauch collects are usually from 15-20 feet, and he notes that this species is variable in coloration, with some of the most unusual specimens having a purple rim all along the edge of the yellow, blade-like branches. This species is known for its ability to slough off its outer skin to rid itself of algae and other debris.

Next Time You Shop, Don’t Forget Florida’s Gorgonians.

It is unlikely that any aquarium hobbyist will ever be able to fully recreate a true slice of the Florida Keys in our home aquariums; Florida’s stony corals are off-limits, and the iconic Sea Fans of the genus Gorgonia are also illegal to collect from Florida’s waters (although legal Gorgonia spp. sea fans have been available on occasion from other sources).

However, that should not dissuade the home aquarist from considering many of the wildly available gorgonians from our local waters. Florida’s marine aquarium fishery is well-regulated and organized, with a long-standing history of private and governmental collaboration. While the nonphotosynthetic gorgonian species can prove quite challenging, most of the photosynthetic species will thrive in the home aquarium once they have survived the transition from the ocean to an aquarium. Their unique growth forms and graceful movement add to the rich diversity of our reef aquariums.

Further Reading:

https://nsuworks.nova.edu/octocoral_guide/

https://coralpedia.bio.warwick.ac.uk/en

https://www.advancedaquarist.com/2004/3/inverts

https://www.kpaquatics.com/product-category/corals/gorgonians-octocorals/

https://reefbuilders.com/2013/01/26/photosynthetic-gorgonians-home-aquaria/

Nicely done Matt; enjoyable style/format and delightful presentation of useful facts.

Bob, those sentiments are very appreciated, thank you my friend!