An adult Ornate Goby, Istigobius ornatus, broodstock used to spawn and rear the species for the first time in captivity. Image courtesy Pei-Sheng Chiu.

Earlier this year, an in-depth study on the breeding and rearing of the Ornate Goby (Istigobius ornatus) was published in the journal Aquaculture Research by Taiwanese authors Pei‐Sheng Chiu, Ming‐Yih Leu, and Pei‐Jie Meng. Having studied the effects of temperature, salinity, and prey densities on the survival rates of this species, the authors believe that their finding “could guide future programs in captive-breeding technology development and commercial production of other marine ornamental gobies.” In short, the open-access article is a worthy read, particularly if you’re interested in breeding saltwater gobies for fun and/or profit!

Admittedly, the appearance of the Ornate Goby doesn’t always live up to its common name moniker. Often cryptically dressed in white-to-beige with black spots, only some specimens appear to show blue dots on their flanks, and few individuals show yellow in the first dorsal fin. Given what’s known of the sexual dimorphism in the Istigobius genus, these more colorful individuals are probably mature males; the researchers noted that their broodstock males had “a more colourful trunk, larger size, and pointed genital papilla,” and Fishbase records suggest that males have darker ventral and anal fins as well.

The Ornate Goby is considered common in the shallows (0-5 m [0-16 ft]) of the Indo-Pacific, and is tolerant of brackish water environments. Mainly owing to its appearance, it’s not common in the marine aquarium trade; according to AquariumTradeData.org, for the years with data available, reported imports ranged from 51 to 222 annually. Most Ornate Gobies arriving in the U.S. over those years were exported from Sri Lanka, and to a lesser extent, occasional specimens entered the trade from Indonesia, the Philippines, and Kenya.

Still, this goby has potential. The authors note, “In addition to being marine ornamental fish, I. ornatus have great potential to fulfill the roles of sand‐cleaners and benthivorous fish in home aquaria—a species that can keep the sand spotless and white and clear off the residues from fish diets.”

Perhaps a rebranding as the “Ornate Sand-cleaning Goby” would be beneficial if aquacultured specimens are ever made available. Captive breeding might also gradually select for more vibrantly colored strains.

Aquaculture of Istigobius ornatus

While the paper is extremely detailed the main point is that the scientists found success utilizing Tetraselmis chui microalgae alongside the smaller-strain S-Type rotifer Brachionus ibericus for initial feedings, followed up with copepodites harpacticoid copepod Microsetella sp., along with brine shrimp nauplii and commercial diets. The authors note that the more commonly seen Brachionus rotundiformis rotifer would likely not be a viable first feeding option for I. ornatus, as their mouths are too small to consume them.

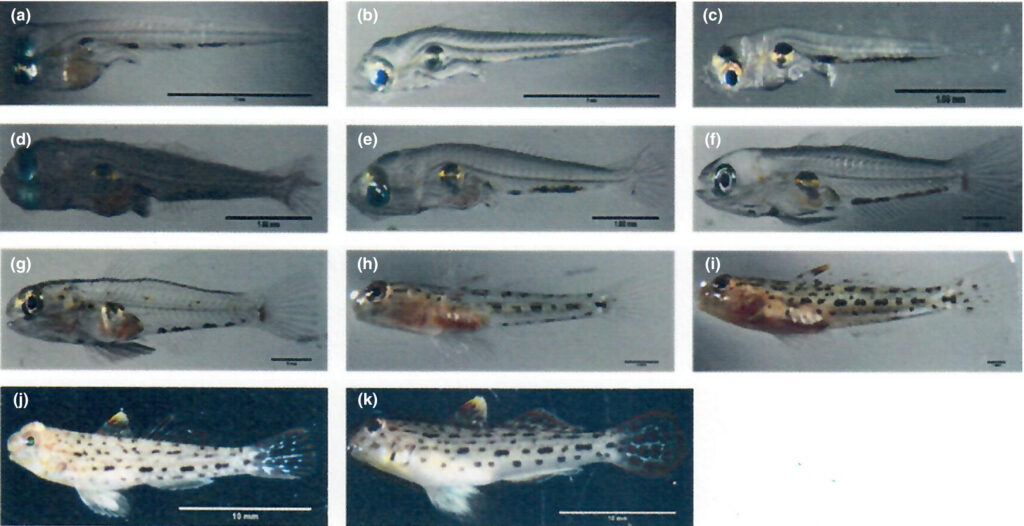

Larval and juvenile development of Istigobius ornatus at: (a) Newly hatched larvae (2.12 ± 0.04 mm TL) with 25–26 somites; (b) 1 day post hatch (dph) preflexion larvae (2.47 ± 0.05 mm TL) with yolk completely absorbed; (c) 5 dph preflexion larvae (2.82 ± 0.005 mm TL) with melanophores on the caudal region; (d) 12 dph flexion larvae (3.53 ± 0.005 mm TL) with an upward turn of the notochord tip; (e) 16 dph post flexion larvae (4.47 ± 0.15 mm TL) with the hypural bone pointed upward; (f) 26 dph post flexion larvae (7.46 ± 0.01 mm TL) with the first dorsal and pelvic‐fins; (g) 30 dph juveniles (7.79 ± 0.006 mm TL) with overall adult number of fin spines and soft rays; (h) 40 dph juveniles (10.16 ± 0.09 mm TL) with full juvenile colouration; (i) 50 dph juveniles (18.27 ± 0.03 mm TL) with silvering in appearance; (j) 70 dph juveniles (4.47 ± 0.47 mm TL) with yellow and red blotches on the first dorsal fin; (k) 100 dph juveniles (4.16 ± 0.31 mm TL) with red blotches on the head and snout. The scale bars of (a)–(h) = 1.0 mm and scale bars of (i)–(k) = 10.0 mm

With thousands of eggs per clutch, there were great opportunities for experimentation. Eggs hatched 84 hours after fertilization. Within a day of hatching, the larvae were able to feed on S-type rotifers. By 12 days post-hatch, the larvae were undergoing flexion, and by 26 days post-hatch they started to settle. They continued to settle as transparent juveniles until day 40. By 50 days they had turned silver, and coloration continued to develop as they fish grew. By 100 days post-hatch, the juveniles started to exhibit territorial behavior and were approaching 4 cm (1.5 inches) in length. It’s worth noting that the maximum length given for Istigobius ornatus by Fishbase is 11 cm (4.5 inches).

More precise breeding and rearing information can be obtained by reading the open-access paper.

Not the first Istigobious bred?

Also of note: the authors wrote that two other species of Istigobius were successfully captive-bred decades prior; specifically, Istigobius hoshinonis and I. campbelli, as documented by Shiobara and Suzuki in the early 1980s. With this revelation, three new Istigobious species will be added to the running tally of CORAL Magazine’s captive-bred marine aquarium fish species list this year!

References:

, , . Year‐round natural spawning, early development, and the effects of temperature, salinity and prey density on captive ornate goby Istigobius ornatus (Rüppell, 1830) larval survival. Aquac Res. 2019; 50: 173– 187. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.13880

Shiobara, Y., & Suzuki, K. (1983). Life history of two Gobioids, Istigobius hoshinonis (Tanaka) and I. campbelli (Jordan et Snyder), under natural and rearing conditions. Journal of the Faculty of Marine Science and Technology, Tokai University, 16, 193–205.