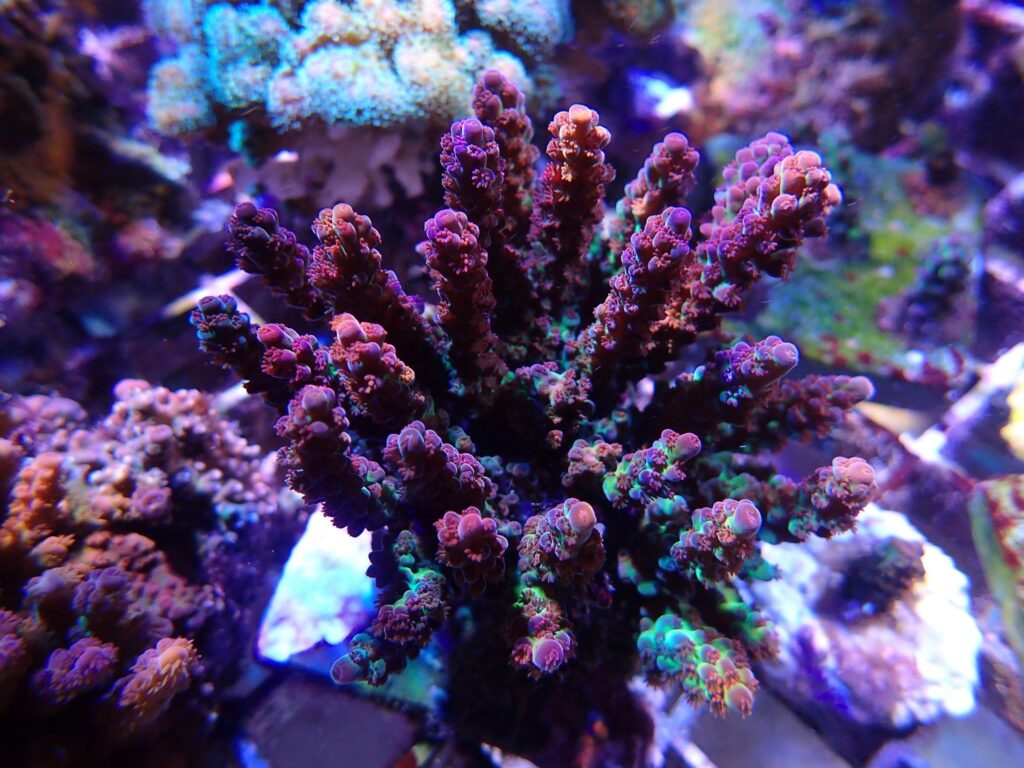

These Acropora digitifera were the offspring that resulted from coral spawning in Guam in 2015, and are now beautiful colonies not even three years later (photographed February 2018).

“Join me on a dive in one of our Acropora baby tanks in Wilhelmshaven, Germany. All of the A. surculosa and A. digitifera were raised from eggs in Guam in 2015 and 2016. Sorry for the shaky camera; I have to improve my camera-holding-device (and my own skills, I guess).” – Samuel Nietzer

Watch Nietzer’s footage, and then read on to learn more:

The shaky footage can easily be forgiven once you realize the vast expanse of sexually-propagated coral on display.

Nietzer, a PhD student at the University of Oldenburg, Germany, is the curator of the aquarium facilities at the Aquarium at the Institute for Chemistry and Biology of the Marine Environment. You may recognize Neitzer as a CORAL contributor.

Most relevant to this video is his article, “Coral Farming 2.0: Sexual Reproduction,” published in the January/February 2017 issue of CORAL Magazine. More recently, he discussed a unique viewpoint with regards to Crown-of-Thorns Starfish in the September/October 2018 article, “Acanthaster: From reef pest to aquarium mascot.”

We asked Nietzer to share more information on this collection of sexually-produced captive Acropora.

“These Acropora were bred during the mass spawnings in Guam in 2015 and 2016 for research purposes and transported to Germany at about three months of age. Since 2010, my wife Mareen (who is part of the same working group) and I have spent most summers in Guam, where we produced the corals for our research and improved our breeding techniques over the years – it’s a great place to conduct work like that.”

“In Guam, we brought the colonies to the lab prior to the spawning date. About a week before the anticipated date, we go snorkeling in the reef right in front of the lab and collect gravid colonies. We bring them to the flow-through seawater system of the marine lab where they are exposed to natural light. The spawning itself happens in the lab facility.

“As soon as the colonies start to prepare themselves for the spawning “setting”, we put them in individual containers. We then collect the eggs & sperm bundles from the individual colonies, then separate eggs from sperm. For the fertilization that takes place in salad bowls, we prepare mixes, e.g. eggs from colony A with sperm from colony B and so on. As soon as the cell division in the fertilized eggs starts, we transfer them into larger tanks where the embryos can develop.

“The parent colonies are not harmed and can be brought back to the reef. Collecting eggs and sperm in the field is also possible, but we always did it in the lab which is really convenient. The only really large downside is that we never get a chance to experience the spawning in the reef ourselves.”

Young Acropora digitifera from the 2015 Guam spawning, photographed in November 2015, three months post-settlement.

Approximately 2.5 years of age, this Acropora digitifera has grown into an impressive and vibrantly colored colony.

“Getting to spawn corals in an aquarium with artificial lighting is very hard, though. This is why we spawn them in Guam and then transport the babies to Germany. Currently, Jamie Craggs is the only one (we know) who can spawn Acropora in aquaria by simulating moon cycle, day length, etc. He’s an amazing aquarist.

“We study the adaptive potential of juvenile corals in the context of climate change/rising sea surface temperatures. Our main focus is on their symbiosis with zoox [zooxanthellae], since it seems the juveniles are still quite flexible in terms of choosing their favorite symbionts. And, like most other organisms, the juveniles have a certain developmental plasticity, meaning they can adapt to their environment to a certain extent. Adult corals don’t seem to be able to change their symbionts once the symbiosis is fully developed, and are limited in their adaptive potential, so we believe the sexually produced babies are key to adapting to a changing environment.

“The corals in the video are currently not used in experiments but are planned to be used in experiments investigating their associated bacteria.”

The conversation turned towards Nietzer’s aquarium hobby, and how the work he’s involved with might have an impact.

“I’ve been a hobby aquarist since I started school at age 6, and had my first seawater tank at 16, so my interest in the potential of sexually breeding corals for the aquarium trade is [immense]! I think there are quite a few amazing advantages about culturing them from (wild-collected) eggs. I see that as the future of sustainable coral production. It also doesn’t require high-tech equipment and it really isn’t rocket science, so it could open a new branch of sustainable aquaculture in producing countries like Indonesia.

Says Nietzer: “I think some of the biggest advantages are:

- The vast numbers you can produce. In 2015, we had 40,000 juveniles of A. digitifera from only three parent colonies. We counted them about two weeks after settlement, so they had already taken up zooxanthellae and had survived the most critical phases. We only needed around 15K for our experiments, so we didn’t keep the other ones.

- The parent colonies are not being damaged during gamete collection. You could technically harvest gametes the next year from the same colonies, which makes it very sustainable.

- The genetic diversity of the babies should make them more resistant against infections (unlike a clonal monoculture). Plus you get a lot of variation in coloration. We don’t focus on coloration for our work, but we see big differences in color, especially in A. digitifera.

- They’re pretty easy to transport. At the age of a few months, they measure only a few millimeters, so you can pack thousands of them into on standard size shipping box.

Hundreds or even thousands of baby Acorpora digitifera in a rearing tank located in Guam, circa 2016, demonstrate the power of coral fecundity when sexually propagated.

“And there are more benefits, like their potential to fuse – in the first months (at least in Acropora), individual polyps/colonies fuse into larger ones. You can grow them to several centimeters within one year if you let them fuse.

“In past years, we bred several species of Acropora in this way (mostly A. digitifera, A. humilis, and A. surculosa, all in Guam). We also breed brooding corals like Pocillopora damicornis and Leptastrea purpurea. One of the future goals would be to breed the LPS species that are hard to frag, like Scolymia, Trachyphyllia, etc. Raising a couple of thousand of those would be amazing.”

What’s on the horizon for Nietzer?

“I recently sent Daniel Knop [Editor-in-Chief of our German-language sister publication KORALLE] an article about a unique coral that we’ve been working with for many years, Leptastrea purpurea. They (at least the population in Guam) release planulae every day, which makes working with their larvae super convenient. The larvae behave similarly to Acropora larvae, so it’s a nice species to do settlement experiments with. With our research, we hope to contribute to the introduction of sexually produced corals to the aquarium trade.”

If things pan out, perhaps you’ll read about it in a future edition of CORAL Magazine!

Image Credits: All images copyright, courtesy Samuel Nietzer

Very encouraging work!

what am i missing here …” We only needed around 15K for our experiments, so we didn’t keep the other ones.”…. what physically happed to the other 25k? Did you send those to other public aquariums , reef clubs to hand out to dedicated reef keepers or ??. just my two cents.