The opening spread of “The High Price Of Being Cheap”, as it appeared in the September/October 2016 Issue of CORAL Magazine. Featuring prominently, The Triton reference aquarium before the tungsten release.

THE HIGH PRICE OF BEING CHEAP

“Made in China”: Consider it a WARNING LABEL

essay & images by Ehsan Dashti – originally published in the September/October 2016 issue of CORAL Magazine

Hobbies cost money—and most of us try to avoid spending too much. This explains why the aquarium market is being inundated by cheap products from China. But can we trust them?

“Cheap is good” seems to be the motto of many people these days, and if the quality of an inexpensive product resembles that of a high-end product, that’s fine. But these days the market is flooded with cheap knockoffs of aquarium equipment, much of it from the Far East—for example, flow pumps that look just like those made by established manufacturers with extensive engineering departments. We aquarists should critically question whether we can expect these products to perform up to our standards.

The main question is whether the materials used to make the copies are actually equal to those used in the original, down to the axis and the bearings. Usually, the cheap versions can only be that cheap because their manufacturers are cutting corners and using inferior materials.

I often read statements on Internet forums such as “The marine hobby has to be affordable, and the large companies are only after our money!” or “Low-cost products are just as good as the expensive originals. A cheap pump might not last as long, but then I just purchase another one and still save money.” Some are convinced that “they are all produced in China anyway! Why not purchase directly from the Chinese? Know-how and experience are simply excuses to make the product more expensive.”

The more copied products hit the market, the more often you hear such statements on the reefkeeping scene. We regularly discuss this at my company and have dialogues on the topic with many large companies in Germany. When we participated as an exhibitor and sponsor at the Marine Aquarium Conference of North America (MACNA) in 2015, we heard similar things from U.S. companies, so we know it is a widespread problem. That is why we decided to get to the bottom of this subject.

Aquarium water is affected not just by salt, trace elements, food, and filter technology, but also by pumps, whose components are constantly in contact with the water. Using our inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrophotometry (ICP-OES) analytics, over the years we have exposed contaminations caused by salt mixtures, micronutrient preparations, and unsuitable pellet foods. Although our company has nearly 10 years’ worth of experience in seawater analytics, we wanted to find out whether using clones or cheap products causes more water contamination than using the high-quality originals they mimic.

ICP-OES analysis: Elements that are collected by default and monitored by us are highlighted in blue. Elements that are always recorded but not considered are marked in light gray. The dark gray elements are not measurable by ICP-OES.

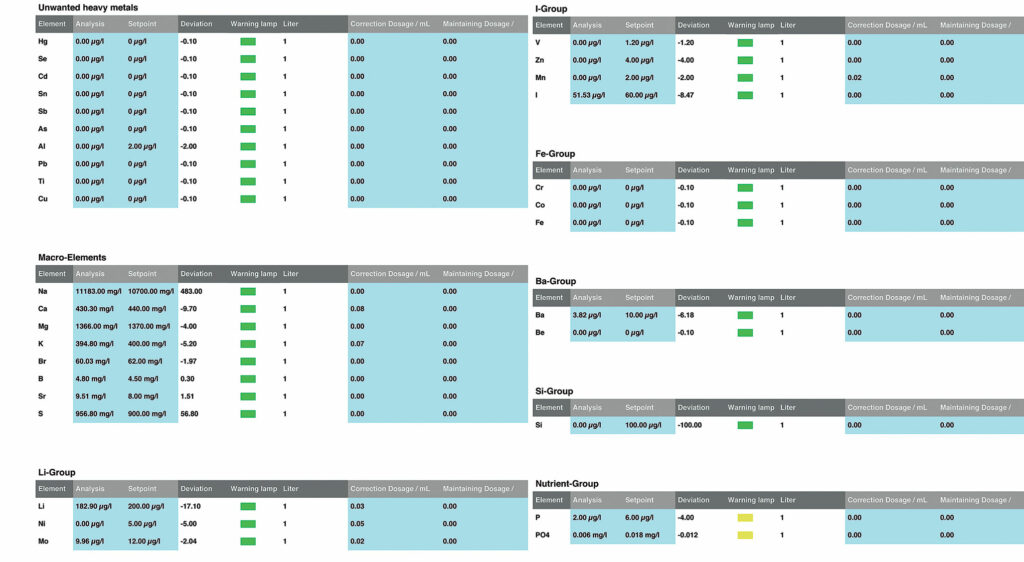

At that time we discovered some unpleasant symptoms in the seawater display tank that serves as a reference tank for our products. On close inspection we noted that some Acropora corals had bare patches and some Montipora corals were looking pale. We closely monitor this reference tank, so we attempted to determine the cause immediately. The trace elements that we routinely examine and document in our ICP-OES laboratory, including metals such as mercury, selenium, cadmium, tin, antimony, arsenic, aluminum, lead, titanium, and copper, were all right and corresponded to natural seawater, so contaminants that would be expected from a defective or unsuitable flow pump were not to blame. We decided to expand beyond the 32 parameters we analyze routinely and include those that are typically detected by water testing in an ICP-OES laboratory, but seem insignificant for the aquarium hobby and are therefore ignored. Overall, we examined 70 elements.

Triton’s evaluation of natural seawater from the Great Barrier Reef. Results from our reference tank were very similar.

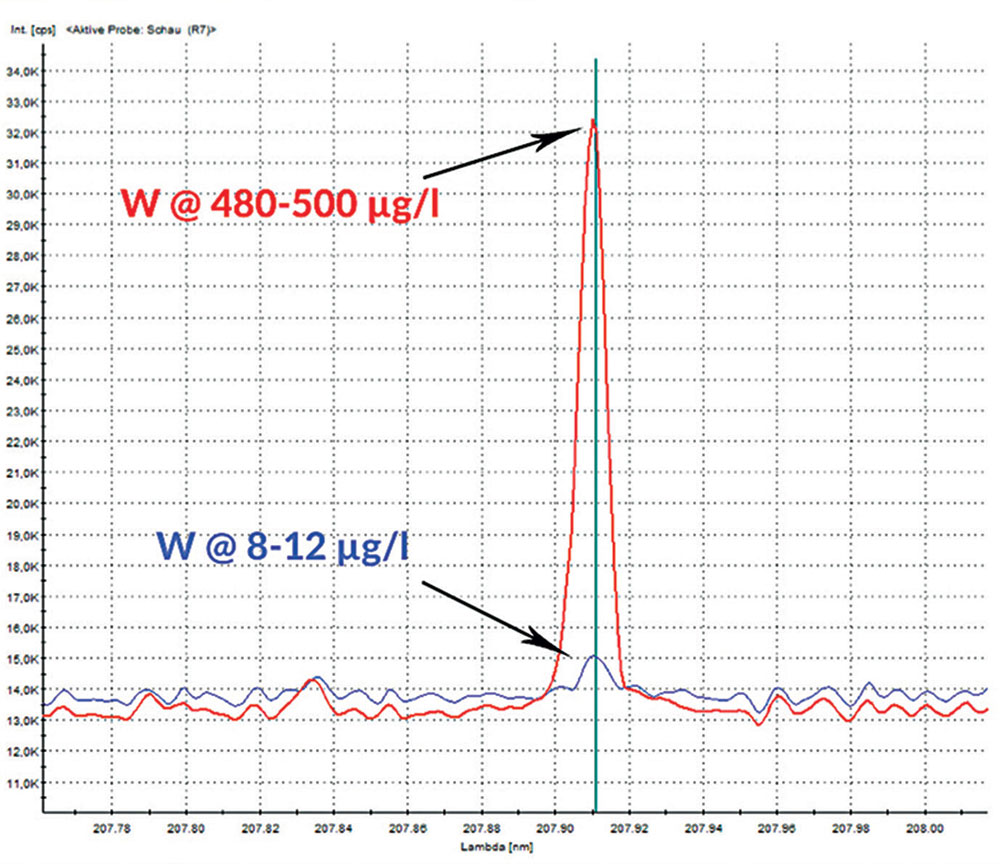

We noticed that a single parameter had dramatically increased and had risen continuously over the course of six months: we discovered a tungsten concentration of 500 μg/L (micrograms per liter). According to our historic documentation, the concentration had previously been 150 μg/L for about a year. The jump made us suspicious, and we started searching for the cause immediately. We excluded all chemical products and other liquids, as well as feed that had entered the tank, because they contained no tungsten. How in the world did tungsten end up in our aquarium water?

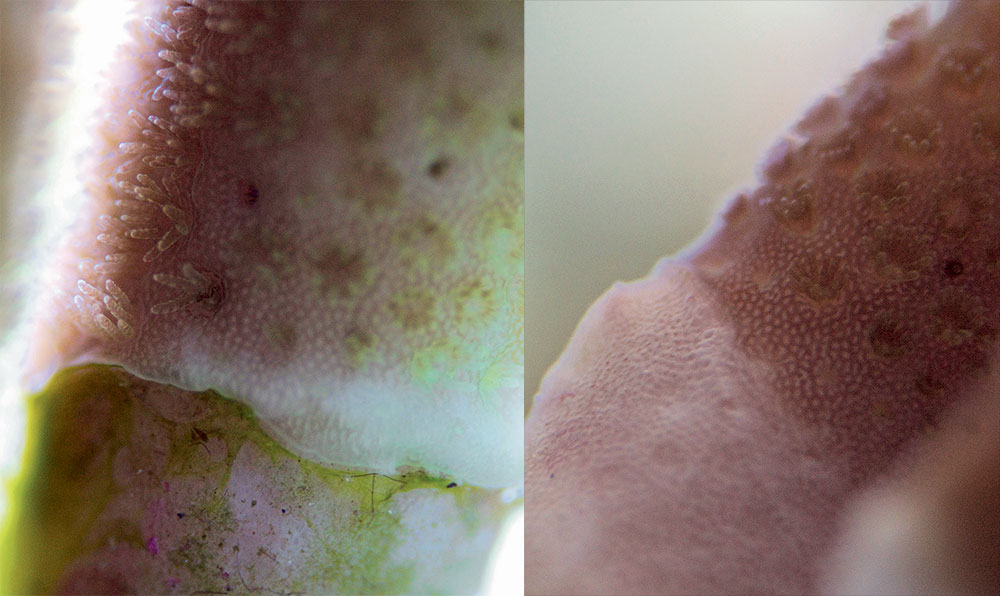

Left: Acropora coral with gradual loss of tissue and encroaching algae. Right: The same coral after the tungsten concentration was lowered. The tissue loss has stopped.

Inspired by conversations I had had with employees of Venotec (manufacturer of Abyzz pumps) at MACNA, I focused on the pumps in our aquarium. I disassembled one of them in order to inspect it more closely and discovered signs of corrosion, which I had previously seen in photographs supplied by customers with problems, both large public aquariums and private aquarists. But the relationship between corroded pump parts and increased tungsten concentration did not seem like a plausible reason to blame the pump, especially because it was not a cheap product—it was in the average price range and was advertised as being fully compatible with salt water. It was, however, made in China.

We mined our data pool of 20,000 aquarium water analyses. We studied the data from aquariums in which damaged or even corroded pumps were mentioned. Were there increased levels of tungsten? Surprisingly, the answer was yes—and not only that, there were also increased levels of cobalt and chromium. An aquarium in London that had used the same pump model also showed increased tungsten levels.

We decided to contact Venotec to talk to an experienced pump specialist and get to the bottom of things. We received the following answer: “Often cheaper shaft material made of tungsten carbide or aluminum oxide is used. In the former, a binder is necessary for the tungsten to remain bound in the crystalline structure. In the best case that is cobalt. But because cobalt dissolves in seawater, the metal is weakened and tungsten can be released. Abyzz uses a special alloy from the food industry that is extremely stable in seawater due to another binder, but unfortunately also more expensive.” These statements corroborated our assumption, but we still didn’t have proof.

Ever since a Chinese pump caused an increase in the tungsten concentration, we have been using a pump made by Venotec in our reference aquarium.

We replaced the two pumps produced in China with Abyzz pumps and conducted a six-month test, closely monitoring the water parameters. The development that we documented was extremely exciting. Since our Triton care method does not include partial water changes, we did not expect the tungsten concentration to fall quickly, but within the first month the colors of the corals improved fairly quickly and the tissue decline stopped. Bare skeletal sites, however, were not overgrown by new polyp tissue. The ICP-OES measurements were still performed daily and fully documented. A daily export of 3 μg/L tungsten was observed in the display tank. When the limit fell below 150 μg/L the corals again started looking very good. Of course, we could have accelerated the decrease in tungsten concentration by doing partial water changes, but we wanted to stay true to our Triton method and see what happened.

The aquarium was operated with a typical Triton filter— an algae refugium, activated carbon, and the aluminum- based phosphate absorber AL99. Below 150 μg/L the tungsten decrease slowed until it reached a standstill at 10 μg/L. To date, this value has not changed.

The tungsten concentration in display tanks before (red) and six months after the pump change (blue), from an original ICP-OES presentation.

We view this development as evidence that tungsten was being released by the Chinese-made pumps we had been using. The lesson we take from this is that you may indeed save money by buying a cheaper pump, but you also purchase some risks along with it—risks that are absolutely unpredictable. Imagine for a moment how the corals in such a poison-loaded aquarium would develop over time if the cause could not be discovered by scientific analysis. The damage and loss would exceed the money saved many times over, not to mention the loss of the animals and the frustration and anger. Therefore we recommend using quality products from tried and true manufacturers who have expertise and reputations to uphold. We also have decided to include tungsten concentration as a new parameter in the ICP-OES analysis.

Alarmingly, our analyses now show more and more small aquariums with rare metal contamination. For those customers who use our method, we know about all the trace element products that enter the water, so we can largely keep these toxins from getting into the water that way. This feeds the suspicion that the cheap products that are increasingly entering the market, mostly made in China, leave unpleasant traces that are difficult for the individual aquarist to recognize.

Ehsan Dashti, owner of Triton GmbH, has been a marine aquarist for more than two decades and is an internationally sought after speaker on water chemistry.

So please tell me, where are the vast majority of the components that make up of non Chinese equipment are made? Fact is the vast majority of aquarium equipment is made in China and there is lots of good cheap equipment that comes out of China. BTW Radion LED are so good they only have a 12 month guarantee as are lots of US made (so called) aquarium equipment. This hardly inspires confidence in a product when the so called high end equipment is guaranteed for only 12 months. Lots of people have been running cheap SB led units for 4 years or more and still going strong. I could go on and give you lots of examples or decent quality cheap Chinese aquarium goods.

In my opinion, this article only refers to a Chinese made part(s), placed in products(water pumps), which then go IN the aquarium water (which they have found to leach tungsten, negatively impacting coral). In regards to LED lighting, made by Chinese, American, German, or wherever, does not relate as these fixtures do not go IN the water. They are not saying all Chinese products, cheap or expensive, are deemed inferior or “bad”. They just noted their findings: some pumps with Chinese parts used a cost saving material on the shaft part that released tungsten into the water, which not only negatively affected their coral but also the many others whom used the same or similar Chinese made part(s)

In which case why not name the pumps that are putting tungsten into the water? If it true whats the problem in naming them? I have heard this “buy cheap pay twice” many times but although that is sometimes the case often it is not. Cheap is supposed to be cheap and inferior be it a pump or a light unit and the fact many high end equipment is made with cheap Chinese parts. I have a Jebao cheap Chinese return pump which I have had running my tank for 9 months are all corals are doing fine and with good colour. I have also used other cheap items like LED units again not an issue and that not only goes for me and my experience but for many others. I have head of various “high end” pumps and LED etc units failing. Sometimes there is a case of one upmanship and even a case of the emperors new clothes in this hobby at times.

I too wish they would name the brand and model of the pump. To claim that pump X, which is not the cheapest pump in the market but “midgrade” level and is very popular and common, has been found conclusively by us to leach a chemical that severely impacts the health of coral, and NOT name the brand/model of said pump is very bad practice. Especially when they share that a top end pump such as those made by Abyzz (which are affordable to maybe 5% of those with private reefs) don’t have this issue….to me it almost gives the appearance that this article is an advertisement for Abyzz (esp with them not naming any other acceptable brand pump). Why not name the pump/brand/company and give them a chance to respond, explain, verify, and/or contribute information, instead of having the readers just guessing as to which pump this may be? If they believe a common piece of equipment is leaching tungsten into the water, harming and literally killing coral, and have evidence to back it up like the article portrays, do they not just have the option, but the responsibility to inform the reefing community? Unless there is some other reason for not sharing this?