First batch of successfully captive-bred Pacific Blue Tangs at day 55 post-hatch. Photo by Tyler Jones.

Craig Watson summarizes the 6-year journey that led to the world’s first captive-bred Paracanthurus hepatus, the Pacific Blue Tang.

A guest contribution from Craig A. Watson, M.Aq., Director of the Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory, University of Florida

Pacific Blue Tangs, Paracanthurus hepatus, are an iconic marine aquarium fish, collected from the reefs of the Indo-Pacific. While plentiful and widespread throughout the region, there is an obvious opportunity for fish farmers to start raising this fish because of the high volume and price. One is hard pressed to find a public aquarium or a marine fish dealer that doesn’t have Pacific Blue Tangs.

There also is an ongoing concern over collecting fish from the wild, and this fish has a lot of collection associated with it. However, like many marine fish, no one had ever produced one in captivity.

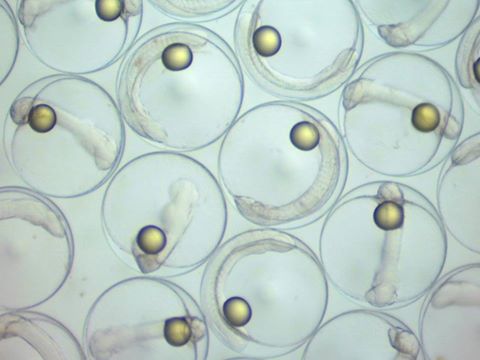

Pacific Blue Tang (Paracanthurus hepatus) eggs collected from broodstock at the Tropical Aquaculture Lab. Egg diameter approximately 750um. All lipid droplets are eccentric. Image courtesy of the UF IFAS Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory

A little over 6 years ago, I was approached by Dr. Judy St. Leger from SeaWorld Busch Gardens about working with the Rising Tide Conservation program. This program had a primary goal of developing production technologies for key marine ornamental species, and Pacific Blue Tangs were high on the list. After agreeing, the University of Florida’s Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory brought in the first group of potential broodstock from a local wholesaler in the summer of 2012 and started conditioning them in a greenhouse for spawning.

Spawning turned out to be easier than first thought, with the fish regularly releasing thousands of tiny floating eggs at dusk, which were skimmed off the surface overnight and collected from nets in the morning. Hatching also seemed to be easy, and happened the next evening. From there it got really hard!

Newly hatched Pacific Blue Tangs are just under two millimeters long, have no eyes or mouth, and are left to drift around in the water for the next two days while they absorb their yolk. During that time they develop eyes and a mouth. If the food for the parents isn’t just right, the yolk won’t be enough, or of the right quality to carry the larvae through. Water quality, including temperature, is critical, and if anything goes wrong they can be gone in hours. But the team worked that out, and survival rates to day 4 got as high as 80% or better.

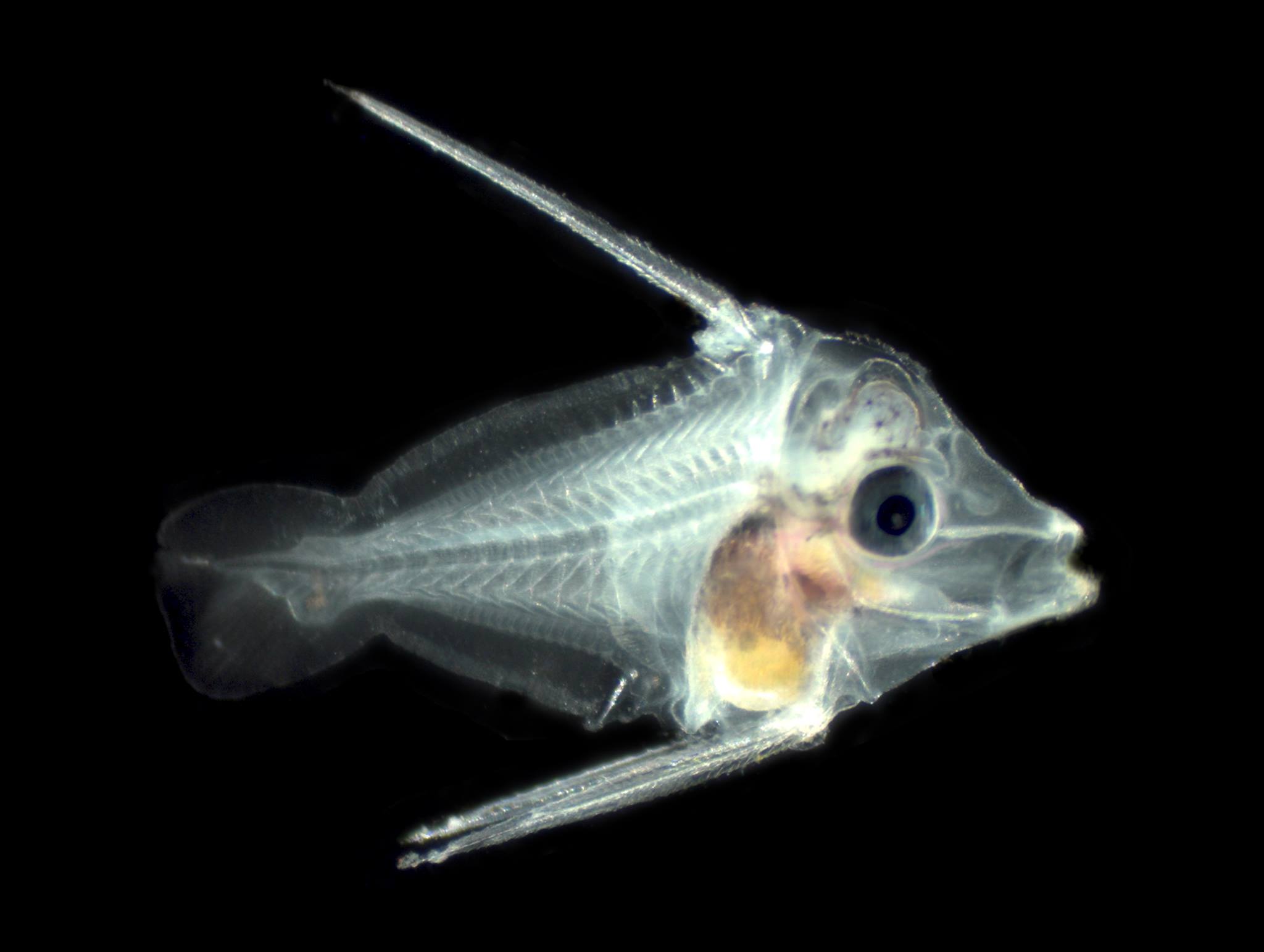

Pacific Blue Tang (Paracanthurus hepatus) larvae, 5 days post hatch. Approximately 3mm long (notocord length). Yolk fully absorbed; eyes, mouth and digestive tract developed. Image courtesy of the UF IFAS Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory

When they first start feeding, like most fish, the food that Pacific Blue Tangs can eat is limited to how wide they can open their mouths, and in this case the food must be only about 40-50 microns . That’s smaller than a period on this page. No one knew for sure just what a tiny tang eats, so the next step was what to feed them? Still just over 2mm in size, a slight mistake in getting the right nutrition into the larvae can mean death in a matter of a few days or even hours. Many researchers have shown that copepods are a main part of the diet of many ocean spawning fish, and that the tiny larvae will target the newly hatched baby copepods, called nauplii. So another aspect of the research became critical – how to raise millions of the tiny, newly hatched copepod nauplii.

Over the next four years a team of scientists at the Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory, the UF Indian River Research and Education Center, and the Oceanic Institute of Hawaii Pacific University started collaborating on Pacific Blue, Yellow tangs and other species, all under the banner of the Rising Tide Conservation program. Despite some promising results, the best the team ever did was get a single Pacific Blue Tang out to 24 days post hatch. Each time the team thought they had discovered something, the same wall was hit, or another one appeared.

Pacific Blue Tang (Paracanthurus hepatus) larvae, 19 days post hatch. Approximately 5mm. Preflexion state – dorsal and ventral spines apparent. Anal spine forming. Body shape deepening. Image courtesy of the UF IFAS Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory

Then in late 2015, Dr. Chad Callan and his team in Hawaii successfully reared the first Yellow Tangs. Given the closeness of the two species, UF sent one of our biologists, Kevin Barden, out to see first-hand how they were doing it. After that visit, UF’s Drs. Matthew DiMaggio and Cortney Ohs got the whole team together and a strategy was developed to attempt to replicate the procedures with Pacific Blue Tangs at both facilities.

Oh yeah…In the midst of all this, Disney and Pixar had announced that a sequel to Finding Nemo was to be released in the summer of 2016, and that the main character was Dory, a Pacific Blue Tang. Like the first movie, it was expected that the movie would be a major boost to marine fish sales, especially for the title character. The race was on!

Like many research successes, it took a team of two UF biologists who really started working on this together – Eric Cassiano and Kevin Barden – to make it happen. They weren’t alone, working with faculty, graduate students, and other staff, but in late May, just weeks before Finding Dory hit the screens around the nation, they started a run at raising the first ever captive-bred Pacific Blue Tangs.

Giving up holidays and weekends, the two produced massive amounts of copepods and other live food, managed water quality, feeding, lighting and other things to closely mimic what had worked in Hawaii. As the days and weeks ticked by, the fish started behaving and growing like nothing seen before.

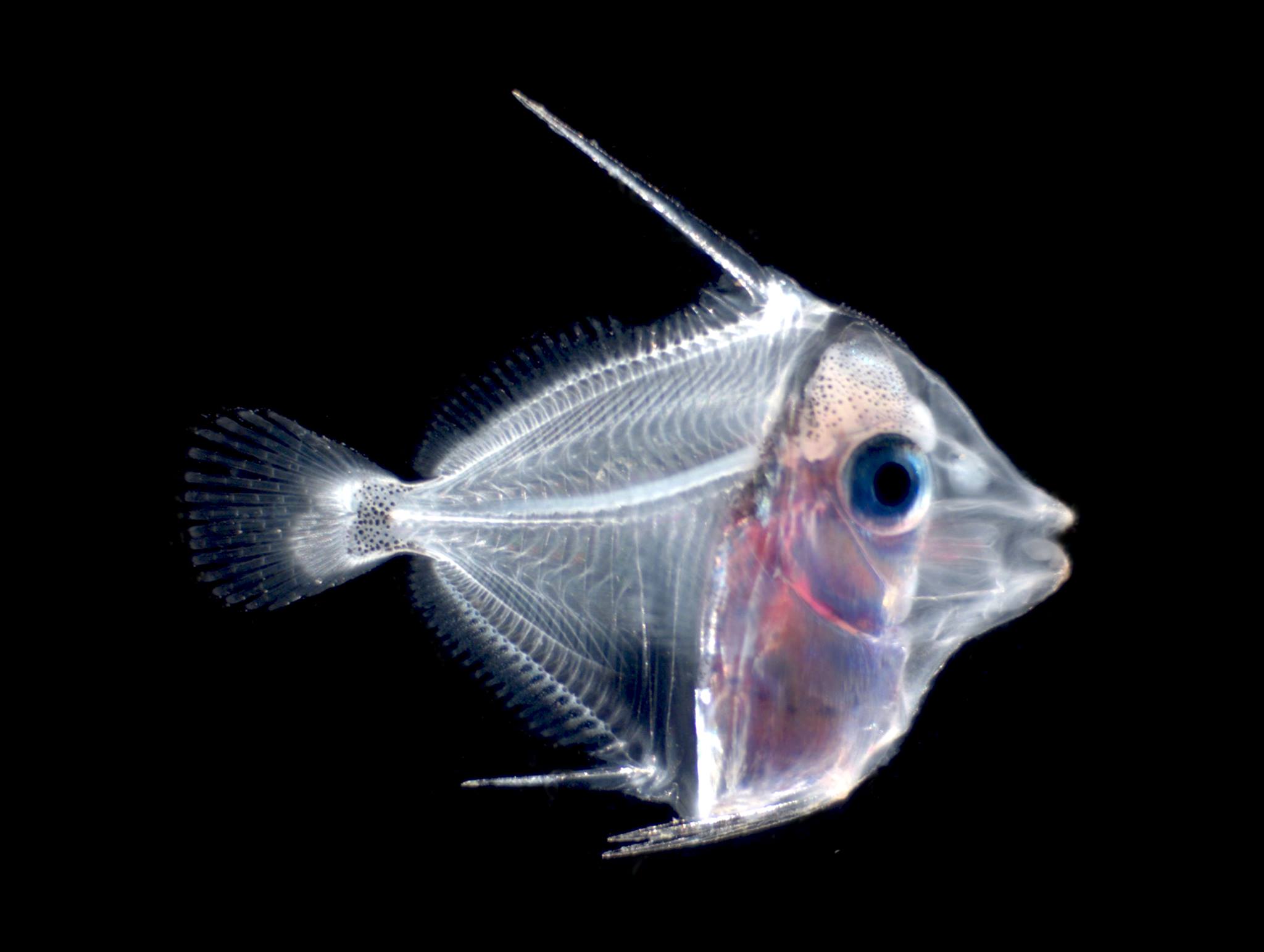

Pacific Blue Tang (Paracanthurus hepatus) larvae, 29 days post hatch. Approximately 6mm long. Anal spine apparent. Cute as a button! Image courtesy of the UF IFAS Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory

Pacific Blue Tang (Paracanthurus hepatus), 33dph. Approximately 7 mm long. Body development continues. Black coloration present at the peduncle. Image courtesy of the UF IFAS Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory

At day 40 post hatch, the fish had started to settle on the bottom, and looked like small replicates of their parents, without the brilliant color. On day 51 the first baby “Dory” was photographed, not on an Indo Pacific reef, but in a greenhouse in Ruskin, Florida.

Pacific Blue Tang (Paracanthurus hepatus) juveniles – 55dph. Now approximately 25mm (slightly larger than a quarter). Blue and black coloration developing. No yellow yet. Photo by Tyler Jones. Image courtesy of the UF IFAS Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory

The work is still not done, as the success is really dependent on a commercial producer being able to replicate what UF did. However, the frustration and challenge today is smaller, just knowing that it is indeed possible. Eric and Kevin are smiling and exuberant, and our industry partners are ready to gear up . What we learned from this success gives everyone hope that it can be repeated when the parents spawn again, and that we will do better the next time. As I write, Dr. Ohs and his team at the Indian River Research and Education Center have a group that is two weeks in and still going. It can be done!

Craig A. Watson is the Director of the Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory under the School of Forest Resources and Conservation, Program in Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, at the University of Florida. He is a Miami, FL, native, and began his career at a tropical fish farm in 1974. Craig paid his way through his undergraduate at Florida State University by working at a local tropical fish store, and afterwards worked for a year as shipping manager of a wholesale tropical fish cooperative in Riverview, Florida. He then spent three years as volunteers in the U.S. Peace Corps in Tunisia, where he assisted in a marine hatchery producing sea bass, sea bream, sole, and shrimp. After Peace Corps he did his graduate work at Auburn University in aquaculture. Craig joined the University of Florida as a multi-county aquaculture extension agent in April of 1988. In 1997, he was appointed director and research coordinator for the newly established Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory. Learn more about Craig A. Watson.

Image Credits: UF IFAS File Photos, photographer Tyler Jones, unless otherwise noted. Used with permission.