The stunning Tigerpyge is a naturally occurring hybrid of Centropyge eibli and the Indian Ocean form of C. flavissima. Tigerpyge are most often exported from Java or Bali.

Tigerpyge to the Rescue

By Matt Pedersen

Images by “Lemon” Tea Yi Kai and Frank Baensch

As first printed in the March/April 2015 issue of CORAL Magazine

I’m going to propose a simple idea that will have certain colleagues of mine, particularly those from the freshwater side of the aquarium hobby, breaking out the pitchforks and torches. I’m going to blatantly advocate for the intentional commercial production of a hybrid fish: the Tigerpyge.

I am not advocating that any breeder approach hybridization in a haphazard fashion or with reckless indifference to the conservation consequences. Instead, it’s a pragmatic stance; if we want to revitalize research, production, and refinement of breeding techniques, hybridization may provide a unique way to circumvent the economic pressures against breeding dwarf angelfishes at this time.

HOW DID WE GET HERE?

Marine angelfishes are pelagic spawners, broadcasting thousands of tiny eggs that hatch into microscopic larvae without eyes or mouths and that must drift in a plankton soup for extended periods lasting weeks or months—some are now known to spend over 100 days in the pelagic larval phase. The fact that Martin A. Moe, Jr., reared any marine angelfishes in the 1970s in the Florida Keys with makeshift equipment is mind-boggling (and due to extraordinary effort), but the fact is that commercial captive culture did not follow for several decades, and even then was accomplished haltingly and with meager production.

We’ve come a long way in understanding reef fish reproduction, but captive-bred marine angelfishes still represent the highest echelon of what aquaculturists can produce. It has been 14 years since the first Centropyge spp. angelfishes were successfully spawned and reared in captivity, first by Frank Baensch of Hawaii-based Reef Culture Technologies in 2001. Baensch fully closed the captive life cycle of Centropyge fisheri just a year later, spawning captive-bred offspring by 2002.

To date, 26 species of marine angelfish have been bred successfully in captivity; half of them are pygmy or dwarf species from the genera Centropyge and Paracentropyge. We’ve also seen the intentional creation of two hybrid forms of Centropyge, bringing the total number of forms to 28. Toward the end of the last decade we saw limited releases of captive-bred dwarf angelfishes, mainly by Baensch’s Reef Culture Technologies. Things were looking good for the fledgling production of aquacultured angelfishes.

With routinely available first-feeds and published methodologies, the last few years seemed like the ideal time for an explosion of breeding efforts and successes with Centropyge spp. and Paracentropyge spp., both groups that included species in high demand in the aquarium trade. As the number of successfully bred marine aquarium fishes now approaches 275 species, with 125 or more species commonly available, there is a growing supply of large angelfish species from Asian farms, particularly Pomacanthus annularis, Holacanthus clarionensis, Chaetodontoplus duboulayi, and C. cephalareticulatus, as well as the early commercial pioneer species Pomacanthus asfur and P. maculosus.

But where have all the dreams of captive-bred dwarf angelfishes gone?

IT ALWAYS COMES DOWN TO MONEY

In the mainland U.S., two commercial producers of marine aquarium fishes are actively working with pelagic spawning fish species that are beyond the ability of most home hobbyists to produce. Fisheye Aquaculture and Proaquatix each currently produce four pelagic-spawning species for the aquarium trade. If anyone could leverage existing expertise and start breeding dwarf angelfishes it would be these two companies, but they’re not.

Jonathan Foster of Fisheye Aquaculture in Dade City, Florida, says the company has no plans to produce Centropyge spp. angelfishes, offering this explanation: “Over the past several years I have watched many facilities (all with far more manpower, more capital, more copepod production, and more knowledge) try this genus out; many even come up with sellable fishes. But none of them do it anymore, and that simply tells me that the yields don’t justify the capital needed for such a venture.” Foster sees the larger Pomacanthus spp. as a more likely focus, should he venture into angelfish propagation.

Eric Wagner remembers a time when Florida-based Proaquatix actively pursued angelfish cultivation. Wagner agrees with Foster: “[Angelfish culture is] tough to do and will take a business down unless it’s [at a] very small scale that doesn’t affect operating budget.”

WHAT COST CB DWARF ANGELFISHES?

Soren Hansen of Sea & Reef Aquaculture in Franklin, Maine, has received grant funding to research the aquaculture of the Flame Angelfish. He muses, “[W]ill aquaculture be able to compete with the price of wild-collected fish [?] How much it will cost [to commercially culture dwarf angelfishes] will depend on the technological advancement and type of live prey used. One thing is certain: it will be much more expensive to culture pelagic spawning fishes—their larval stage is so much longer.”

Karen Brittain, an active and pioneering marine angelfish breeder from Hawaii, couldn’t put a number on the cost. “Angelfish production cost is mainly about the time spent (the cost of your time to raise the fishes) and…the cost of keeping the broodstock, hauling water, and purchasing salt, electricity, water, fertilizer for algae, larval tanks, nitex screen, etc. Right now…it is not economically feasible for most species.”

In Honolulu, Frank Baensch, arguably the most experienced breeder of dwarf angelfishes on the planet, has a similar response. “My main cost by far was labor (a typical Centropyge rearing day started at 5:00 a.m. and ended at 7:00 p.m.). The next biggest cost was electricity (mainly temperature control). The cost of producing a Centropyge can vary tremendously and depends a lot on your location and the species you’re working on.” Baensch places a lot of emphasis on manpower expense for larviculture, along with broodstock costs and feeding expenses. He also points out the high capacity needed for dwarf angelfish growout due to aggression: 1 gallon per juvenile, minimum.

A surprising answer came from Syd Kraul of Pacific Planktonics, a fish hatchery based in Kailua Kona, Hawaii, another pioneer in Centropyge breeding. Although not a high-profile breeder, as of 2015 Kraul is likely the only active commercial producer of Centropyge angelfishes, and he flies below the radar because his production is sporadic and batch numbers aren’t high. “With many years of effort, I can still only raise 100 or so angelfishes at a time,” he says. Kraul is currently producing only Flame Angelfish (Centropyge loricula); his fish enter the trade without any identification as captive-bred (noteworthy in that prices must be competitive with those for wild fish). His comments suggest that the cost to produce dwarf angelfishes might be far less than we assume. “The main cost is failure to produce enough fish, unless you are producing very expensive fish.”

THE MATH IS BRUTAL

While I’d like to believe that our hobby would be willing to pay a substantial premium for a captive-bred version of a marine aquarium fish, history paints a much different picture. The difficult-to-stomach reality is this: the price of a wild-caught species currently sets the top price most captive-bred fishes will command in most circumstances. Virtually any commonly available dwarf angelfish—species like the Coral Beauty, the Lemonpeel, the Halfblack, the Cherubfish, the Midnight, and the Rusty—often retail for only $25 to $45 in the U.S. Informed speculation suggests that in most small-scale scenarios, the base cost of producing captive-bred versions of common dwarf angelfishes could far exceed the current wholesale (or possibly retail) prices of their wild-caught counterparts. The only people I know who are willing to attempt breeding common species without any hope of financial gain are home hobbyists and researchers, and neither collective seems very interested in producing dwarf angelfishes at this time.

Pragmatically, the bulk of wild dwarf angelfish species retail well below $100 in most settings; only a few species occupy the average hobbyist’s “expensive” price range of $100 to $500. By most accounts, the dwarf angelfish species that hypothetically work for commercial cultivation, given today’s knowledge and practices, are the rare, truly expensive, and ultra-expensive. At the low end are species like the Joculator Angelfish (Centropyge joculator), which seems to retail around $700 in most venues; Centropyge interrupta, which was around $2,500 the last time I saw one; C. narcosis, which sold for $5,000 here in the U.S.; C. nigrocella, which was reportedly offered in Japan with a roughly $16,000 price tag; and the holy grail Peppermint Angelfish (C. boylei), whose price is rumored to be $20,000 to $30,000.

With their ultra-high price tags, species such as this may be seen as economically viable candidates for propagation. However, you need to have the access to broodstock, the capital to invest, and the risk tolerance to even consider playing in that league.

What if we could change the rules of the game?

CREATE YOUR OWN RARE FISH

Perhaps the creative small-scale breeder could tear down the economic barriers by raising and selling highly desirable hybrids. The production of hybrids might be the key to getting people and businesses breeding dwarf angelfishes again. Hybrids could make captive propagation work by freeing breeders from price competition with wild fishes, as well as keeping broodstock acquisition costs low.

Singapore’s Tea Yi Kai suggests that the Tigerpyge is no longer truly rare, with “dozens” being found since 2009. Still, a specimen offered by a U.S. wholesaler in February 2015 retailed for $1,500 or more.

The fish that inspired this idea is the one that Reef Builders editor Jake Adams has named the Tigerpyge. This naturally occurring hybrid, resulting from a Lemonpeel and Eibli’s Angelfish cross Centropyge (flavissima X eibli), tends to carry a price tag around $1,200 to $1,500. If you want a Tigerpyge, get ready to stand in line and, if you’re lucky (and connected), you might get a shot at one…in a few years. It’s fair to say there isn’t a “wild fishery” specifically for Tigerpyge. As a breeder, you don’t really have wild fishes to compete with.

But as a breeder, how do you go about breeding Tigerpyge? Do you have to spend thousands of dollars and years amassing rare broodstock, one fish at a time, as they become available, in the hopes that one day you can produce this fish? Of course not. Anyone reading this can go out right now and get the appropriate fish for less than $50 U.S. each, retail, and have them in his or her tank by the end of the week.

Remember, the Tigerpyge is a hybrid; it is the mating of the parental species that creates it. Enough individual wild-caught specimens of Tigerpyge have been documented to illustrate and reconfirm a generally understood rule of hybridization: primary hybrids, the initial crossing between two species, tend to produce very consistent and predictable results.

THE MATH OF HYBRIDS

Consider Syd Kraul’s earlier figures; the best he can produce is about 100 Flame Angelfish offspring per batch. If you’re as good as Syd Kraul is today, you can rear 100 Flame Angelfish with a retail value of around $60 per fish, or $6,000 per batch. Or, for the same effort and cost, you could raise 100 Tigerpyge with a conservative retail value of $100,000.

It looks amazing on paper. Even when we factor in the presumed downward pricing pressure from increased supply, let’s say a value of $600 retail per fish, that’s still a $60,000 retail value per batch. Of course, that doesn’t mean the farmer sees $60,000 unless he somehow retails every last fish himself, but the story is simply this—producing something like the Tigerpyge could bring in 10 times the amount of revenue with a virtually identical amount of effort.

I must also temper expectations by noting that ongoing production of a fish like the Tigerpyge, particularly if considerable volumes are being pumped into the market, would dramatically drive prices down. One only has to look at the retail values of the Lightning Maroon Clownfish (Premnas biaculeatus “PNG Lightning”). From first introduction to today, depending on how you choose to calculate the numbers, this rare variety has lost somewhere between 80 and 98 percent of its original “stratospheric” retail valuation.

Overproduction can quickly devalue a rare fish, but thankfully, not every dwarf angelfish breeder is Syd Kraul. What if a propagator was experimenting with dwarf angelfish production and had just $200 to invest in broodstock? What if that effort was only going to produce 20 fish during his entire first year of effort? This is where it gets really interesting, because 20 captive-bred Lemonpeel Angelfish, while desirable, simply wouldn’t pay the bills. However, a limited production of only 20 Tigerpyge, which could likely maintain a retail value of $1,000 or more per fish, might just do the trick.

RISKS OF HYBRIDIZATION

I cannot endorse hybridization as a commercial pursuit without briefly reacknowledging its risks and past history. Hybridization is effectively irreversible and can be very damaging to species purity, which is an important concept in conservation of species. Professional producers are more likely to understand these risks and avoid the pitfalls. Since marine angelfish production seems largely confined to commercial organizations at this time, I simply lack the concern I would have if angelfish breeding were as ubiquitous and accessible to hobbyists as clownfish production has become.

With that in mind, the pursuit of confusing hybrids between similar-looking species is not something that any savvy commercial propagator would pursue in the first place. Do we really have to see the result of mating two largely all-yellow dwarf angelfish species, such as C. (heraldi X flavissima), to know what it’s going to look like? There is really no upside to creating this hybrid; only a fool would pay more for it than for the pure parental forms.

Instead, it is the more divergent pairings that have the potential to be real showstoppers, and the offspring wouldn’t be confused with any pure species. Any breeder looking to leverage the power of hybridization to hit an economic home run is going to pursue hybrids that stand apart from any pure species that can easily be obtained, either by re-making a hybrid already known from the wild or dreaming some really big dreams.

CENTROPYGE HYBRIDS — MOTHER NATURE’S EXAMPLES

The Tigerpyge was the inspiration for this idea, but several additional known hybrid dwarf angelfishes are regularly found and photographed or collected in the wild. Hypothetically, these should all be fishes that breeders can re-create, although Frank Baensch notes that simply putting two disparate species together may not result in crossbred offspring.

Naturally cohabitating pairs might work to create some hybrids, particularly in pairings between closely related species where behavioral cues or other factors may encourage fraternization. Other hybrids might be achieved through novel broodstock systems that synchronize spawning of conspecific pairs while encouraging gametes to migrate between broodstock tanks. Production would be sporadic and unpredictable in such a setting. A better way may be to synchronize nightly spawnings but intervene before actual spawns occur, using manual methods to harvest gametes from parental fishes and then artificially mixing gametes to create a new generation of hybrid offspring.

There is no single repository for the records of every known marine angelfish hybrid, and that is why the would-be breeder is encouraged to review the books and hit the Internet to find these almost mythological apparitions. I will briefly call out two additional candidates besides the Tigerpyge that I think could prove to be true winners for commercial propagation.

The Rusty Angelfish is involved in a couple of hybrids, the most attractive one, in my opinion, being its hybrid with the Multicolor Angelfish, Centropyge (ferrugata X multicolor). At first glance it resembles the Multicolor parent, but it quickly seduces you with a warmer color pallette. Instead of the whiter flank of the Multicolor, it has a pale orange flank color that shades into deeper red toward the anal fin. The Multicolor parent largely blocks out the spotting and barring seen in the Rusty parent. The fish is topped off with a blue crown and dusky fins with blue highlights and edges.

There is one dwarf angelfish hybrid that puts all others to shame. It is the hybrid of the Multibar and Purplemask Angelfishes, Paracentropyge (multifasciata X venusta). It’s a very rare hybrid, and it stops people in their tracks. The throat and ventral fins are yellow, and the anal fin is yellow with white and blue scrawling. The vertical barring of the Multibar Angelfish remains, but it is transformed into a graphic twisting, swirling pattern that covers the entire flank and fins in a mixture of white and black in almost equal proportions. Blue highlights at the rear and tips of the dorsal spines and around the yellow eye complete the package. The commercial breeder who re-creates this fish stands to make a tidy sum.

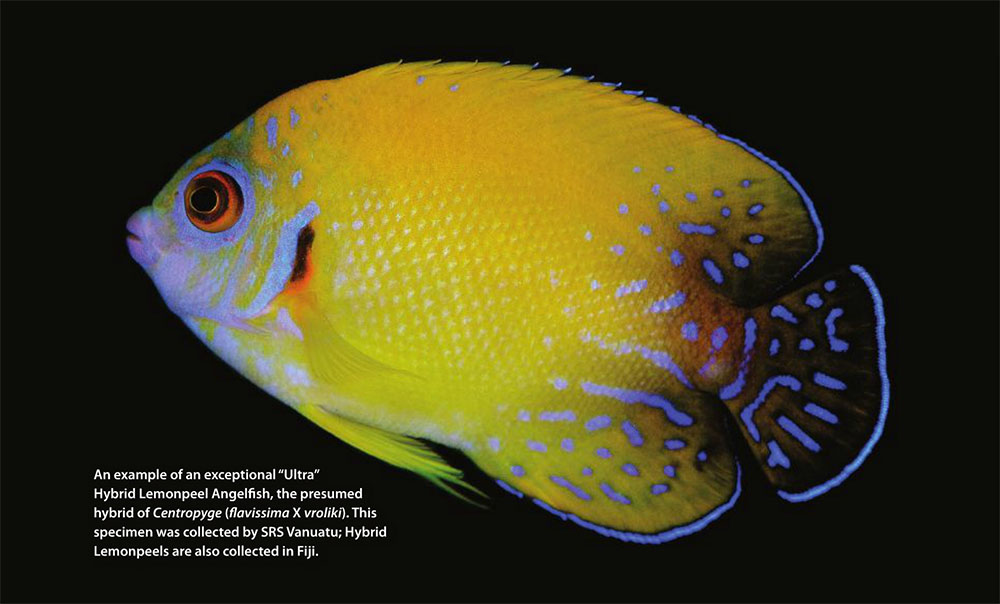

An example of an exceptional “Ultra” Hybrid Lemonpeel Angelfish, the presumed hybrid of Centropyge (flavissima X vroliki). This specimen was collected by SRS Vanuatu; Hybrid Lemonpeels are also collected in Fiji.

LEMONPEEL AND “ULTRA” HYBRIDS

While these are my top picks, I also encourage you to look at the many diverse forms of “Hybrid Lemonpeels,” the general industry shorthand for suspected hybrids of Centropyge (flavissima X vrolikii), or Lemonpeel and Halfblack/Pearlscale. These fishes are relatively common from the wild; the more mundane imported fishes are not even that expensive, and therefore would not provide the financial boost needed to make propagation viable at first glance. However, among these fishes are a subset of “ultra” hybrids, fishes that seem to originate with some frequency from Vanuatu.

Rare fish connoisseur Tea Yi Kai, known as “Lemon,” believes that the wide variation seen in these hybrids is due to ongoing generations of interbreeding and backcrossing. In the end, intentional captive-hybridization of these parental species, as well as working with some of the “ultra” forms if you can get them, could provide a modest price bump and also provide potentially valuable insights into the reproductive interactions between these species as they occur in the wild.

On Mother Nature’s list of accomplishments, take a look at the Pygmy Kingii, Centropyge (vrolikii X eibli); the unnamed hybrid of C. (heraldi X bicolor) and the similar Bicolor Groucho Angelfish, C. (flavissima X bicolor); the creatively named Flame Beauty, C. (bispinosa X loricula); the unnamed C. (potteri X fisheri); the unnamed C. (multicolor X bispinosa); and the False Shepardi Angelfish, C. (ferrugata X loricula).

Beyond these hybrids, consider both of Frank Baensch’s manmade hybrids, the Resplendent Cherubfish, C. (argi X resplendens) and the Hawaiian Resplendent Angelfish, C. (fisheri X resplendens). It is interesting to note how matings between similar species with similar color patterns can produce less-than-exciting results—fishes that don’t stand out enough to warrant high levels of interest (or payment), and may even be misidentified as pure species by the casual observer.

Top: The Hawaiian Resplendent Angelfish, Centropyge (resplendens X fisheri), was produced in 2006 and was Frank Baensch’s first successful captive-bred hybrid angelfish. Below: Baensch’s 2011 hybrid, the Resplendent Cherubfish, Centropyge (resplendens X argi), illustrates a hybridizer’s rule of thumb: similar-looking parents produce similar-looking offspring.

IS THERE A CB CENTROPYGE IN YOUR FUTURE?

It’s not all doom and gloom for the future of captive-bred dwarf angelfishes coming from local hobbyist breeders. Those with the most experience perhaps have the most optimism. “I do think that the backyard/basement hobbyist breeders have a better chance of making a profit from angelfishes than large-scale operations in the U.S.,” says Karen Brittain.

Frank Baensch sees the rewards, and the risks, when he uses himself as an example: “Producing small numbers of rare Centropyge can be a profitable venture at a small facility like mine. The problem is that prices will drop quickly if the species is no longer deemed rare.”

Syd Kraul serendipitously addresses the risk Baensch mentions with a different strategy and an optimistic view. “I am hopeful that I can increase my angelfish production to profitable levels this year…My strategy is different than [others]. I am purposely doing the fish that have a good price when lots are available from the wild, instead of those whose price depends on scarcity. I intend to sell a few thousand fish per week.” Kraul suggests that by the summer of 2015, Pacific Planktonic’s focus will be exclusively to produce aquacultured marine aquarium species.

Kraul may not be the only one looking to ramp up dwarf angelfish production. Matthew Carberry of Sustainable Aquatics reveals that current plans are already underway specifically to bring angelfish culture to Tennessee. “We are currently building an additional broodstock system specifically for angelfishes (stands and tanks are already in place). The live feeds are also ready.”

Carberry’s response looks beyond the simple economics toward necessary changes the aquarium industry might need to consider. “Why culture Centropyge? Of course the obvious answers come to mind: Adding angelfishes to our currently available tank-bred fishes would make for a very attractive pricelist. Having healthy tank-bred angelfishes trained to eat pellets would help more stores and hobbyists to have success with these sometimes delicate fishes.

Carberry continues: “As with other species that have followed this pattern when cultured, the hope is to reduce the price on some Centropyge species to make them more accessible. Culturing them would reduce collection pressures on these fishes where there are increasing efforts to restrict or close collection for marine aquariums (especially Hawaii)….”

Could the intentional pursuit of captive-bred hybrids help fuel a resurgence of breeding efforts focused on breeding dwarf angelfishes? On paper, the pursuit of hybrids makes instant economic sense; it eliminates price competition from wild fishes and, in fact, creates a largely new product that didn’t exist before.

Perhaps most interesting is the notion that, by considering the production of hybrids, the barrier to entry for first-time propagators would be lowered. Simply put, with more potential upsides, the rewards may finally outweigh the risks. Considering the relative stagnation in this area of aquaculture and in research, perhaps it’s time we got small-scale, passionate breeders excited about producing Centropyge or Paracentropyge once more.

—

Matt Pedersen is a CORAL senior editor and the first to breed the Harlequin Filefish and Lightning Maroon Clownfish. He currently works in his home-based culture facility in Duluth, Minnesota.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks