Fresh out of graduate school, I began my career as a public school teacher full of enthusiasm. I wanted to share my passion for learning science with the next generation of students. My dream fell short, though, when I experienced the reality of working in an urban public school.

I found myself teaching 2nd grade in a large elementary school where the majority of students lived in poverty. The stress of living poor had imparted many students with social and emotional challenges that they brought with them to school each day. It seemed that they often felt lost within the inconsistency of their lives, not knowing when their clothes would be washed or which relative’s house they would sleep at each night.

Naïvely, I starting teaching my students with earnest good cheer and artful but scripted lessons that immediately flopped. Kids didn’t care, didn’t learn, failed tests, and acted out. With time, I realized that my students weren’t looking for trouble, but power over themselves. The routine of school had become one of the stabilizing forces in their lives, a safe place with reliable adults. And paradoxically, the place where they felt comfortable enough to vent their negative feelings and advocate with good or bad behavior for control over the world around them.

I tried for over a year to find ways to empower my students and stumbled onto something big when I brought a 5 gallon tank into my classroom for two of my troubled boys to take care of. Two students that affected disdain for friendship, learning, and simple kindness fell in love with a 1-inch tetra because it was theirs.

They learned the first lesson of aquarium keeping: that aquarists are in total control over the life inside their tanks. Finally, something depended on them, and the responsibility needed to keep the fish alive and happy started to transfer to the care they took with others and, later, themselves.

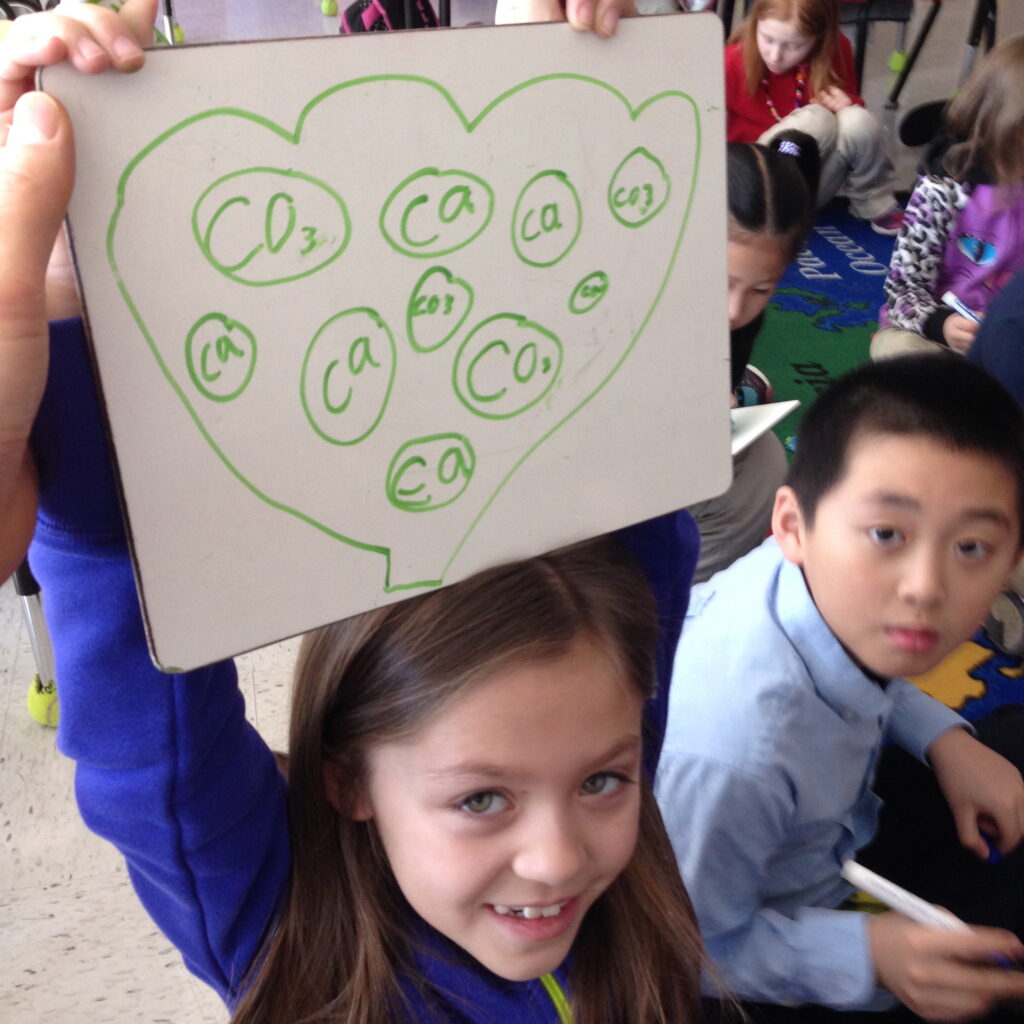

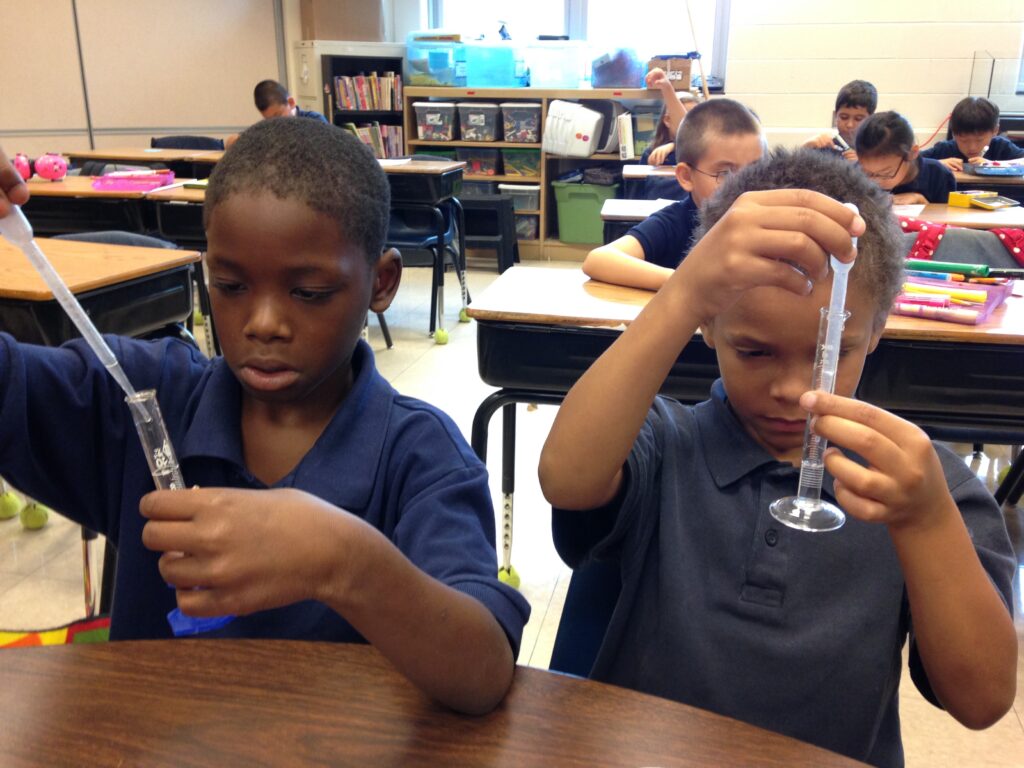

That was the beginning, and now I have built over 1,000 gallons of marine and fresh water aquariums around my school. I have created a multi-year school project that builds aquariums for classrooms and teaches students marine biology and aquarium keeping. Each day, student leaders care for the aquariums in their classrooms and teach the next generation of peers how to do so as well.

In the blog posts to follow, I hope to share my views on elementary education, the perspectives and experiences of my students, and ways in which parents and other teachers can use aquariums as learning tools for children.

I am a retired ENT Physician and presently the chairman of the education committee of Clearwater Audubon Society in Clearwater,Fl. I have been interested in getting more youngsters involved with nature and biology.Our chapter started a program called Audubon Explorers however this year we cancelled it because of poor participation.Reading about your success once again excites me and I will try to adapt some of your ideas. I’m also going to pass this article to a middle school science teacher in our organization ,as well as, the head of education at the Clearwater Marine Aquarium.Keep up the good work. Lynn Sumerson

Hello Dr. Sumerson,

I appreciate your interest in my project and I encourage you to continue to try to connect kids with science. Like any new venture, finding the way forward will involve trial and error. From my experience, the student interest will almost always be there provided that the program makes kids feel involved and empowered through working with nature and science.

I’m guessing that part of the poor participation involved the political and logistical problems that are present whenever one tries to change or create programs in public schools. I would be happy to talk over ideas with you, but in the meantime I can share some of the things that have helped my project.

The adults who initially start an organization are usually committed but the adults (parents) who later participate may not. It is vitally important to solve as many problems for these initial participants as you can. Transportation, snacks for kids, reminding people of event locations and times, having equipment and activities prepared, paying for things, providing clear instructions etc. are all necessary to make the people beginning to participate on the project feel successful. Only after you have established a large group of committed and pleased participants can you delegate more responsibility back to other adults involved.

Teachers are overworked and administrators and educational policy often constrain what projects they can complete or promote in schools. It is very important to document the academic relevance of potential projects using state learning standards. It is also very important to create media in the form of photos and examples of student work to prove the merit of the project and encourage others to participate. Teachers can use this documentation to argue for projects with their principals and parents.

Most kids want to do something fun first and consider the educational merits later. I think carefully about what experiences new children have when they first join my project. I hook them in with novel and easy activities and they require them to learn how to do more arduous tasks later.

The best training I’ve had as a teacher was a 3 year program called EnLiST created by the University of Illinois. It is entrepreneurial leadership skills for STEM teachers. Influencing school curriculum and creating and promoting projects is just simple entrepreneurship. Fortunately there is a wealth of training out there for business owners and canny, enterprising teacher cans make use of them.

I am by no means an expert on teaching, aquariums or business but I do like to solve problems so please consider me a resource. I’d by happy to share ideas about educational programs. Please contact me via email at rutherbr@champaignschools.org if you’re interested.

This is wonderful. Thank you for caring so much. I wonder if this sort of thing would work with the mentally ill as well? I’m thinking especially of depression and addiction. The combination of control, caring and a connection with nature seems to be a perfect fit.

Hello Lesley,

Thank you for your comment and kind words. I think that aquarium keeping and animal husbandry in general has many therapeutic benefits. Though I am a general education teacher, I have some training in supporting children with mental health issues and work with many children who are in need of emotional support.

In my community, we have a mental health organization that has their own school and a very large residential home for foster children. From my understanding, both places have aquariums and also work with local groups that use therapy dogs and cats. A simple google search will yield many resources that document the use of animals as therapy. I’ve been slowly reading a book called A Handbook on Animal Assisted Therapy. Excepts are available online and it contains several chapters that discuss the use of animals in psychotherapy.

If my personal experience is of any relevance, I have worked with children that have been exposed to horrific events and there isn’t a 100% percent effective way to support them, especially in a public school setting. As many therapeutic supports as possible should be used and aquariums and animal husbandry are definitely a powerful tool.

This is awesome! I study “science as leisure” and one of my major points is that keeping an aquarium teaches science concepts! Would you allow me to use your photos in a presentation and poster on the topic? I am really interested in learning more too. Let me know! elizabeth.marchio_at_gmail.com is my e-mail. Check out my webpage and newest blog post on the topic!

http://lizmarchio.com/thats-so-ich/starting-an-aquarium-uses-science/2015

Sounds like we have a lot in common, I’ll email you shortly. I really enjoyed reading your essay in Science. Many of the scientist I know developed their interest through keeping pets or being in nature. You should post the link here so others can read it.

First off, I just wanted to say thank you for all that you are doing for your students. I am a speech-language pathologist out in California and a novice aquarist (only about 2 years into the hobby). I was interested in starting a small 5-10 gallon aquarium for my students. It would not be something I would do immediately, but I wanted to do a little presentation for my colleagues regarding the many benefits of having an aquarium in the classroom. Would you be able to share any direct STEM (or even STEAM) applications in the elementary and junior high setting? I can think of some biology, ecology, and chemistry lessons, but I am sure you have much more experience when it comes to translating it to curriculum lessons.