Giant Grouper on display at the Georgia Aquarium. Home aquarists can buy baby specimens of this same species in local pet shops. Image: Dilif/Wiki Commons.

By Ret Talbot

A new paper in the journal Marine Policy (“The 800-Pound Grouper in the Room: Asymptotic Body Size and Invasiveness of Marine Aquarium Fishes,” Holmberg et al.) is critical of the aquarium trade practice of selling fishes unsuitable for most home aquarists. In particular, the paper looks at some of the largest fishes—some which exceed 100 cm (39 in.) as adults—that are commonly available to novice aquarists as relatively inexpensive juvenile fishes. While the authors acknowledge within this paper and elsewhere (Tlusty et al. Zoo Biology, Rhyne et al. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability) the global aquarium trade has the potential to become a positive conservation force, here they also point out how these large fishes can lead to one of the largest ecological risks of the home aquarium hobby–the introduction of nonindigenous species.

Their argument is that these so-called “tankbusters” are more likely to be invasive than suggested by how common they are in the trade. This suggests there are specific motivations behind intentional releases that have proved ecologically and economically devastating in states such as Florida. If an aquarist is more likely to release a so-called “tankbuster” over a fish that will never exceed an adult size of 20 cm (8 in.), what actions can the aquarium industry and state and federal agencies take to limit the trade in these large fishes and, in turn, reduce the risk of non-native introductions?

Data Reveal Big Problems

The paper analyzes over 5,000 records representing 775 species of fishes for sale at five well-known online marine aquarium retailers—Live Aquaria, Blue Zoo Aquatics, Petco, Reefs2Go, and SaltwaterFish.com.

Emperor Red Snapper juvenile, a future tankbuster for sale on the Internet, offered by Live Aquaria.com. This species can grow to 116 cm and 33 kg (46 inches and 72 pounds).

For each record, species, size and price were recorded, and several interesting observations emerged. According to the study, 113 of the 775 species in these data have a maximum length of 40 cm (16 in.) , while several are known to grow in excess of 100 cm. The largest fish commonly available to marine aquarists is the Bumblebee or Giant Grouper (Epinephelus lanceolatus). These fish, while often sold online or at the local aquarium store at less than 20cm, can attain a length of 270 cm (almost 9 ft.) with a maximum published weight of 400 kg (aka “the 800-pound grouper in the room”).

Not surprisingly, the authors learned that fishes that remain small tend to be sold “at retail sizes equivalent to or greater than their theoretical maximum size,” while tankbusters tend to be sold at relatively small sizes. They also learned that, relative to their size, many future behemoths are relatively inexpensive fishes.

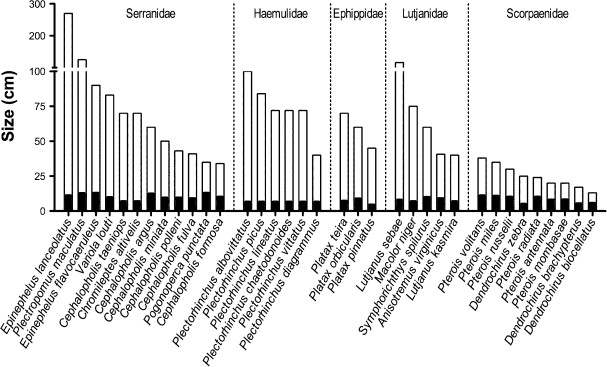

Because the authors were interested in looking at tankbusters, they focused on four families of fishes that generally grow too large for the typical home aquarist: Serranidae (groupers), Haemulidae (grunts), Ephippidae (spadefishes), and Lutjanidae (snappers).

“These species are of particular concern,” the authors argue, “as they are unsuitable for most home aquaria beyond more than a few weeks of their early life histories.” While E. lanceolatus is the most extreme example, the paper shows that at least two other aquarium species—Plectropomus maculatus (Spotted Coral Grouper) and Lutjanus sebae (Emperor Red Snapper)—can also exceed 100 cm.

Average median retail size (solid bars), compared to the maximum potential size (Fishbase) for common large species of marine fish in the aquarium trade including Serranidae (groupers), Haemulidae (grunts), Ephippidae (spadefishes), Lutjanidae (snappers), and the lionfish of Scorpaenidae.

Tankbusters & Invasive Species

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) maintains the Nonindiginous Aquatic Species (NAS) database, which tracks non-native species in U.S. waters. The NAS database shows that nearly 30 non-native marine species of fishes imported to Florida for aquarium use have been observed in Florida waters. Surprisingly, however, these species do not correlate directly with import volume.

If aquarists are releasing fishes into the wild because the hobby is too expensive, the aquarist is moving, or some other factor is causing the aquarist to break down his or her aquarium, one might expect to observe a correlation between the most imported fishes and wild sightings of nonindigenous fishes. “This is not always the case,” the authors observe, “indeed, several marine [nonindigionous species] are uncommon in the trade, so their presence cannot be explained by volume of import alone.” The authors theorize that there must therefore be some “selective force” influencing the release of marine aquarium species.

Could tankbusters be that selective force? It seems plausible given that Cephalopholis argus (peacock hind), Chromileptes altivelis (panther grouper) and Epinephelus ongus (white-streaked grouper) have all been observed in Florida waters. While not ranking high in overall imports compared to the popular aquarium species, these tankbusters are all imported and sold to aquarists as juveniles. In addition to the species mentioned above, the authors point to documented reports in Florida of other large marine ornamental species such as Chiloscyllium punctatum (bamboo sharks), Rhinecanthus aculeatus (white-banded triggerfish) and Rhinecanthus verrucosus (blackbelly triggerfish). As the authors state, “These species likely exceed 30–40 cm within one to two years.”

Juvenile Giant Grouper, Epinephalus lanceolatus, offered to home aquarists by the online web merchant, Blue Zoo Aquatics in Los Angeles.

Given these fishes’ life history and the unsuitability for long term care in the vast majority of home aquarists’ tanks, they are perhaps some of the most likely candidates for intentional release into the wild. They also happen to be fishes with the best chances of surviving in their new environment given their size and the fact they are commonly released as larger juveniles or adults. Of course unsuitability based on size is not the only potential reason an aquarist might release a fish into the wild. Aggressive fishes and fishes that may consume other ornamental species (e.g., coralivore butterfly fishes) may also be likely candidates for release into the wild, but, as the paper shows, release into the wild of tankbusters appears a likely pathway for nonindigenous species.

Assessing the “Real” Risk

Nonindiginous and invasive species pose tremendous risk to ecosystems and economies, and so it is important to develop and implement risk management strategies in places like Florida where the risk is greatest. Unfortunately, legislative efforts to address these issues are often based more on public perception than data. Even administrative rulemaking can fail when public perception and other stakeholder voices obfuscate the data. Recently Florida, through administrative rulemaking, imposed an import ban on all lionfishes from the genus Pterois. While the State had an opportunity to pass a rules package that could have effectively addressed the risk posed by nonindigenous marine fishes, they instead only focused solely on the genus to which the one invasive species (Pterois volitans/miles) belongs.

As the authors of this paper show, when compared to the extreme tankbuster examples, lionfishes attain only a moderate size. The well-publicized and invasive P. volitans/miles is the largest species in its genus and likely poses the greatest risk. Banning the import of all Pterois lionfishes and allowing the importation of other species from other genera, some of which grow larger than banned Pterois spp., shows a disregard for life history data. If Florida is going to ban the import of all lionfishes in the genus Pterois, including P. mombasae, which only attains an adult size of 20 cm, it certainly seems reasonable that they would consider also banning the import of an aquarium species that can grow more than 10 times larger and weigh as much as 400 kg. This is especially the case in a state where it is illegal to sell, barter, or trade of any saltwater product without a valid license, removing the option of selling an unwanted or unsuitable fish back to the vendor.

Next Steps – A “Moving White List”?

Given the risk to ecosystems and economies, it is crucial to develop and implement effective, data-based risk management strategies, and the paper’s authors propose one such path forward. They say that, while the aquarist is a well-documented pathway for nonindigenous species introductions, clearly all the responsibility cannot be placed on the individual aquarist, who may or may not act in a responsible manner. Instead, the authors argue, choke points must be identified. “The consumer has access to and possession of high-risk species because they were made available by the trade.” In other words, addressing availability at the trade level is a much better way to address the risk. “[E]xplicitly discouraging the importation and sale of high-risk species is the most precautionary approach,” write the authors.

The authors suggest largely uncoordinated trade efforts to date have been ineffective and must change or be improved, but there is really no substitute, they say, for recognizing tankbuster fishes as largely unsuitable for inclusion in the aquarium trade. As long as retail vendors continue to sell tankbusters, the authors suggest those vendors should take full responsibility for the species they sell and be required to buy back any large species, regardless of the size at which they are sold. “If stores were held accountable for oversized fish,” the authors contend, “they would likely be more hesitant to sell them initially.”

Removing the most offensive fishes from trade is the preferable option, and the authors propose that the aquarium trade should create a multi-stakeholder workgroup that could curate “an adaptable list of species with high invasive potential. More specifically, they propose “a stakeholder-based management plan in which industry, government, and NGOs develop a moving white list that guides consumers away from high-risk species.” This group would have the knowledge and latitude to be able to make exceptions to such a list, and they would also be able to recommend disallowing the importation or trade of a known invasive species to or from a given region based on a data-based risk assessment model.

“For example,” the authors write, “if a guideline was set to prohibit species that exceed 30–40 cm…from the trade in order to reduce the occurrence of [nonindigenous species] in Florida, the working group may choose to exclude moray eels from the list. Despite their length, moray eels do not require as much space as pelagic species, and thus may not qualify as high-risk ‘tankbusters.’ The multi-stakeholder workgroup could condone the sale of moray eels while reserving the right to limit them in the future should research suggest they are high-risk.”

Likewise, they write, “Exclusion zones may be considered that weigh the relative risk of a species becoming established based on habitat suitability, a concept that is considered for managing invasive plants. A tropical species has much higher probability of becoming established in the waters of south Florida or the Caribbean than in the Northeast or Midwest where either no marine habitats exist or winter water temperatures fall well below the thermal minimums for tropical species.”

Mixed Response

The publication of “The 800-Pound Grouper in the Room: Asymptotic Body Size and Invasiveness of Marine Aquarium Fishes” in a peer-reviewed scientific journal concerns some in the aquarium trade. They worry that advertising the ready availability of fishes unsuitable for home aquaria by almost anyone’s definition makes the trade look irresponsible. One industry insider called the paper “irresponsible,” arguing that it disproportionately focuses on the risk of a very small segment of the trade. Critics say it is unfair for the entire trade to have to change because of a few irresponsible individuals.

“My feelings are that we already regulate unsuitable species and trade in very few quantities of those species that are very unsuitable for the aquarium trade,” says one principle at an import-wholeslae facility. “It doesn’t take a genius to know what species are not very desirable or have a high mortality rate.” He argues the trade quickly learns which of those species to avoid when making purchases. Another importer-wholesaler worries that banning tankbusters will push the trade in “monster fish” underground, adding that monster fishkeeping is becoming more popular. “Instead of maintaining some level of traceability,” the importer-wholesaler says, “the supply chain becomes opaque, and that’s not a good thing for the longevity of our hobby or our industry.”

A freshwater behemoth, the Redtail Catfish, is an aquarium favorite at small sizes but is notorious for outgrowing tanks. Image: Monika Betley/Wikipedia.c

While there are concerns about the paper and its effect on the public’s perception of trade, there are also those who say they welcome the multi-stakeholder approach put forward by the authors. Although many in trade are less than enthusiastic about any sort of white list, they do see value in reaching consensus about species that pose the most risk. Several importers, wholesalers and retailers express frustration that they are unable to unilaterally choose not to deal in certain tankbuster species even when they think doing so would be the proper course of action. For many, it’s an economic issue—if they don’t offer these species and other vendors do, the customers will go elsewhere.

Perhaps the best example of customer-driven economic incentive to deal in tankbuster species is the Redtail Catfish (Phractocephalus hemioliopterusis). This large catfish is a species that epitomizes the tankbuster definition and yet is commonly available to aquarists. As one wholesaler, who no longer offers the other “monster catfish that get three feet long” explains, “I tried to drop [the red tail catfish] for two years, but customers will move entire orders to another vendor for that specific fish, and we lost a lot of money. It’s one of the smartest fish and most personable, but I don’t think they should be in trade.”

If there were data-based, trade-wide consensus on which tankbuster species pose the greatest risk—and if all importers, wholesalers and retailers could agree to not deal in those species—it’s hard to see how that wouldn’t be a step in the right direction. As the authors of the paper conclude:

Creating a not-for-sale species list is a step that must be undertaken by a coalition of the willing. If not, the continued appearance of invasive species will force draconian regulatory action that will have a large suite of unintended consequences, and will greatly limit the trade. Given the rich biodiversity of the trade, removing a small handful of species from commercial trade that pose the greatest risk should be viewed as a positive step.

Ret Talbot is a CORAL Magazine Senior Editor and a photojournalist covering issues of sustainability and science in the world’s fisheries, including those serving the marine aquarium trade. He lives with his wife Karen, a conservation artist and scientific illustrator, in Rockland, Maine.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks