Puget Sound King Crabs, exceptionally slowly growing crabs, with a massive adult body, are among the most colorful animals found in the Northeastern Pacific. They live most of their life in deep water, but come up into the shallows to molt, and incidentally display their vivid freshly molted color.

Over the years, I seem to have acquired a reputation as a crab-hating individual. Nothing could be further from the truth. I like to watch crabs, and I have enjoyed raising crabs. And, of course, I love to eat crabs… mmmmm… ah…. Mmmm

However, crabs have no place in a coral reef “community-type” aquarium for quite a number of reasons. Those reasons are obvious and have been beaten to death in various forum venues, articles and elsewhere. Nonetheless, the lack of crabs in our tanks robs us of the ability to watch some of the most interesting marine animals. One really fun thing about crabs is that they, like all arthropods, of course, grow by “shedding their exoskeleton” or molting. This process, in and of itself, is tremendously interesting. But, there is another thing that the molting process allows. It gives us a good way to see changes in the animals’ shapes as they mature.

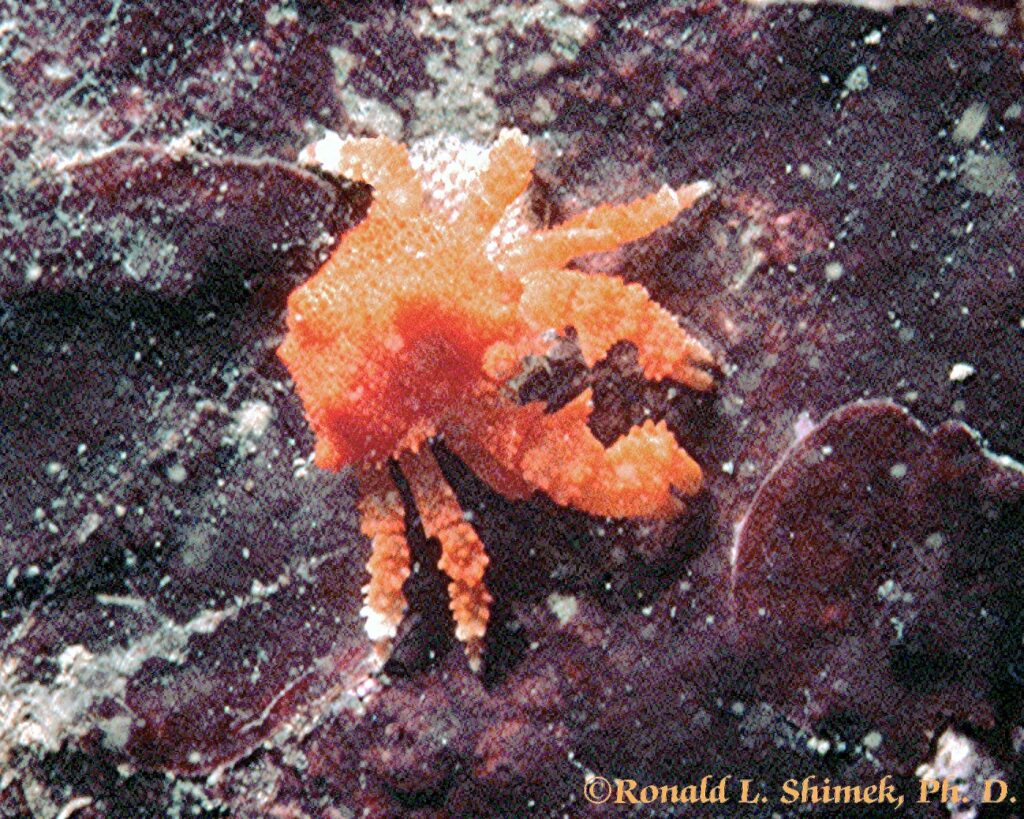

Compare the color and shape of this young Lopholithodes mandtii to any of the figures with older individuals. The age of this animal was estimated to be about 2 years. Although I slightly tightened up the focus, I didn’t alter the color in this or any image – nor did I collect ANY live specimens of this species. In another blog, perhaps, I will tell you why :-). The two best thing about these little guys (this one was about 2.5 cm (an inch) long) is that they are gregarious, so if you find one, a little bit of looking will often find 3 or 4 of its buddies, and they seem to “think” they are camouflaged. And maybe to certain predators with funky color vision they are. But for humans… these stand out like little neon beacons.

Back in the last millennium, when I was actively doing diving research, I took a liking to some peculiar crabs, the lithodids. I didn’t do any research on these crabs, directly, but one of my friends did, and one of the things he wanted me to do was to collect any of the molted exoskeletons. If these are carefully collected, and then if they are carefully positioned and left to dry in an area where they won’t be disturbed, the resulting mount is a perfect 3-D record of the size of the animal before one molt. If enough of these molts are collected, it is possible to get a pretty good idea of the size of the animal at each molt. And then, if other data are available, such as the age at a given size, it is possible to get a very good record of changes in shape and size over the lifespan of some potentially representative animals.

This Puget Sound King Crab was probably about 4 or 5 years old when its picture was taken. Notice the changes in shape from the youngster shown above. Nobody, as far as I know, has any good idea of what these small L. mandtii eat.

Lithodid crabs are related relatively closely to hermit crabs, and while they don’t have an asymmetrical and soft abdomen that needs protection in a shell, their abdomens are asymmetrical. And additionally, as do hermit crabs, they only have three obvious pairs of walking legs, the fourth pair being reduced and held protectively near the back. Some lithodids get quite large, the various northern king crabs are such animals. These crabs doe not live as far south as the areas I did most of my research, but those areas had a far more colorful lithodid, the Puget Sound King Crab, Lopholithodes mandtii. And just so you understand, I would propose that there is no more spectacular coloration found in a crab than is found in THIS species of crab. As you see here, they start their lives as blaze orange babies and then add colors as they age. The colors, of course, are most spectacular after each molt.

A young teenager, this Lopholithodes mandtii is about 10 cm across the carapace, and was estimated at age of 12 to 15 years old. Shown sheltering under an individual of Cribrinopsis albopunctata. Recently molted lithodids of all species seem to shelter under large anemones, presumably to get protection from predators such as octopuses which would certainly eat them if they could find them in an unprotected place.

My crab-researching friend, over the 10 to 15 years I sporadically worked with him accumulated a lot molts of L. mandtii. What he found was quite interesting, and very surprising. When one of these crabs settles out of the plankton to metamorphose into a tiny juvenile, it is only a few millimeters long. To the best of my knowledge, I can’t recall anybody ever finding one that was below about a centimeter in width, which is probably an age of 3 to 6 months old. They were reasonably common at a size of one and a half to three centimeters, which probably is an age of up to about three or four years. Then we got a few individuals that molted at about 10 to 15 cm in width, which was an estimated age from 10 to 15 years old.

This young fella was estimated to be around 20 years old. When they get this large, they seem to start eating their adult prey. These are some of the few animals that will eat sea stars. They will also eat sea urchins. As one might expect from looking at this critter, these animals are slow and rather ponderous in their movement.

After that size, we seldom ran across any that were not full-sized individuals, which were relatively HUGE. The ones that were about a meter across the leg span were probably about 25 to 30 years old. The really big ones, about 1.3 m across the legs, he estimated to be from 60 to 100 years old.

This is a small adult male Puget Sound King crab a bit less than a meter across the maximum leg span. The abdomen of the female he is guarding is visible at the top of the figure. As in most, probably all, crabs the males of this species molt first, and harden up, and then find a female that has yet to molt. They pair up, and he guards her from other males until she molts. As she molts, she releases her eggs spawned at the previous molt a year before. While she is still soft, but he is nice and hard, he mates with her. She then deposits her eggs under her abdomen and her integument gets hard over the next couple of days. During this period her mate protects her and his offspring. After which they go their separate ways.

The Puget Sound King Crab is an exceptional animal in all sorts of regards, and I hope to visit it here again, soon.

Until later,

Cheers, Ron