Culturing the vulnerable King of the Parrotfishes

By Tom Bowling

Excerpt from the May/June 2014 issue of CORAL Magazine

Palau is unique in many ways. Part of Micronesia in the Western Pacific Ocean, it is a biologist’s wonderland consisting of amazing mushroom-shaped islands, isolated ecosystems full of rare and endemic species, and some of the healthiest reefs and estuaries in the world.

Conservation is strongly embedded in the Palauan culture, and this is evident: Palau has the world’s first shark sanctuary and has undertaken initiatives such as protecting animals that are globally endangered or under threat, including the Bumphead Parrotfish (Bolbometopon muricatum), the Napoleon Wrasse (Cheilinus undulatus), and many others. Because it is small and isolated, Palau is also uniquely suitable for predicting the gathering of spawning fish aggregations. This makes it an ideal place to track the aggregations and collect gametes (fertile fish eggs) in high densities for research on cultivation.

The Biota Aquaculture hatchery was originally built to breed Siganids (rabbitfishes), which we now do, in order to restock the local waterways. We are producing Dusky Rabbitfish (Siganus lineatus), Lined Rabbitfish (S. fuscescens), Twin Spot Snapper (Lutjanus bohar), and Bumphead Parrotfish (Bolbometopon muricatum), plus a handful of ornamentals like seahorses, cardinals, and clownfishes.

Currently we release an average of one million well-developed Dusky Rabbitfish fry into the ocean every month. The fish are about 5–10 days old and about 0.2 inch (5 mm) in length, and although the majority of these fishes will fall prey to other fishes, there is a significant increase in survival odds for every day of “head start” that they get. We are now in the process of establishing community-based growout facilities so that Palauans can grow their own rabbitfishes for sale and consumption.

Capable of reducing a ton of coral a year into beach sand, the fused teeth of a mature Bumphead can exert tremendous biting force.

Biota Aquaculture’s collection techniques

Biota Aquaculture has obtained special research-based permission to collect eggs from spawning aggregations of many fish species. This has resulted in an exciting first year here in Palau: using this technique, we have been able to produce species that are world firsts, including the Bumphead Parrotfish (Bolbometopon muricatum) and the Red Snapper (Lutjanus bohar).

Fortunately, Unique Dive Expeditions (Sam’s Tours Palau) has been studying these aggregations for some time and made them accessible to me and other experienced divers on a monthly basis. This means I can get to the site, about an hour away, collect the just-spawned eggs, and get them back to Biota’s facilities with relative ease. I am able to collect the eggs in good numbers (approximately 25,000 per trip) and with relatively little damage by using a specially designed net. The task requires a lot of swimming around once the fishes start spawning. They are fairly shy of divers, so I have to time it just right in order to get the most eggs without chasing the broodstock away.

The collection of naturally spawned wild gametes has one of the lowest environmental impacts of any aquaculture method. The egg survival rate is extremely low in the wild (95–99 percent mortality, according to professor Howard Choat of James Cook University), and there is no effect on any adult fish.

Bumphead Parrotfishes at the moment of gamete release. Daily events such as this can see hundreds of thousands to many millions of eggs released.

Therefore, there is minimal impact on any fish population compared to other techniques, such as holding broodstock in containment or catching wild fishes and artificially inducing them to spawn. Estimates of spawning aggregation gamete output (total number of eggs) range from hundreds of thousands per day to tens of millions per day.

A strong indicator that Bumphead Parrotfish spawning is about to begin is schools of Midnight Snapper (Macolor niger) lining up and ready to feast on the eggs that are about to be spawned. These snappers have gill rakers that they use to sieve the eggs from the water column by the thousands. There is also a healthy shark population waiting for a dining opportunity, so we often find ourselves shoulder to shoulder with some big bull and silky sharks. They are pretty focused on the fishes, so we never really feel too threatened, though every now and again we turn around and are startled to see a 12-foot bull shark cruising behind us within arm’s reach.

The author with an egg collection net. Approximately 25,000 eggs are collected per event, with minimal environmental impact.

Breeding parrotfishes

I am only familiar with a few scientific attempts to rear parrotfishes using “artificial” spawning methods (strip spawning). I also know of many reported captive parrotfish spawns. I have been unable to find documented evidence of any being raised in captivity. We are excited to be the first to rear Bumphead Parrotfish—and perhaps the first to raise a true culture of the Family Scaridae!

Of course, the only way we were able to do this was to use the wild egg collection technique; it would be extremely difficult and costly to maintain a breeding population of Bumphead Parrotfish in captivity. Scarids are very sensitive in captivity; they are easily stressed and usually require special feeds. The cultured Bumpheads we have produced are obviously quite different, as they are accustomed to being in an aquarium and seem to do well on a combination of live enriched Artemia and pelletized aquaculture feed.

After several attempts at rearing, we managed to rear more than 100 Bumphead Parrotfish. This is by far one of my most exciting career achievements, and if it weren’t for the opportunity I have had here in Palau, there is no way I could have accomplished it.

The ecology of Bumpheads

The Bumphead Parrotfish, Bolbometopon muricatum, is the “king” of the parrotfishes. It is the biggest at almost 5 feet (1.5 m) and has an incredibly large head, which it uses to ram opposing males during courtship. There are even accounts of it ramming coral heads in order to eat the broken pieces. It is also a delicacy, which is why it is now considered “vulnerable” and a “species under threat” around the world. (It is one step away from an IUCN Red List classification of Endangered.)

In Palau, however, as a direct result of government protection, the fish occurs in great numbers. It is a corallivore, meaning that it eats mostly coral and calcareous algae, and one fish can produce up to 2,200 pounds (1 metric ton) of sand per year as it consumes and passes stony corals through its digestive tract. The adults cruise the reef flats like a herd of bison—it is quite a spectacle to behold. They are generally peaceful and very easy to fish for at night. This has been their downfall and, sadly, they are only a memory in many island nations throughout the Pacific.

The Bumphead Parrotfish gathers to spawn at known places, such as fast-flowing channels or reef outcrops, every new moon. They aggregate in the thousands and gather into a compact school on the reef before streaming out together into the blue to commence spawning. The males change color to half white and half grey-green, which seems to signal to the females that they are ready—or perhaps they are warning other males to back off. Then the spawning female swims with small bursts of speed until all the nearby males rush her, trying to be the one to get closest to the newly released eggs. If you are lucky, when the males are still courting you might see two of them ram each other at high speed; the impact sounds like a firearm going off.

Parrotfish larviculture

Direct stocking is not easy. I have had great success with some attempts, but most have failed when trying new species. The successful attempts seem to result from focusing on volume, as this gives the larvae plenty of drift space but also keeps parameters such as salinity and temperature constant. This method seems to be favorable for Bumpheads, although I have yet to run more trials and verify this.

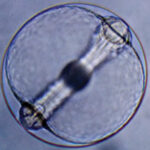

For our first successful run, I stocked all 25,000 eggs into a 3,963-gallon (15,000-L) nursery tank. The eggs are incredibly transparent, so it is difficult to gauge egg health and hatch ratios; we just had to wait! I applied very gentle but evenly spaced aeration, and we filtered the water down to 20 um and applied UV sterilization. We had to carefully separate the eggs from the mix of alien plankton, which can contaminate the wild eggs, although using treatments like iodine certainly helps to reduce the number of predators and parasites.

The fish hatched in approximately 24 hours and were so small I actually considered releasing them into the sea and forgetting the whole idea. After day 3 the yolks were completely absorbed and the fry began to swim in a more controlled manner. We stocked the tank at five rotifers per millileter, utilizing a particularly small rotifer species. They seemed to be small enough as a first feed, and it didn’t take long to verify this by sampling a few under the microscope. The rotifer culture was held in a greenwater tank, and we also added Isochrysis regularly. It is difficult for us to find any commercially available algae or enrichments here in Palau, but I am sure our yield will increase once we can do this.

In my initial trials I stocked the tanks with algae, rotifers, and copepods prior to introducing the fry. Our successful run, however, was achieved by direct stocking to filtered ocean water only. We added some algae later on for filtration, but the water was always kept clear. We filter the water at 20–30 um but do not shock or treat the water further.

I believe that in the first “fill,” there were also many microplankters in the water. Perhaps these also contributed to the first feed.

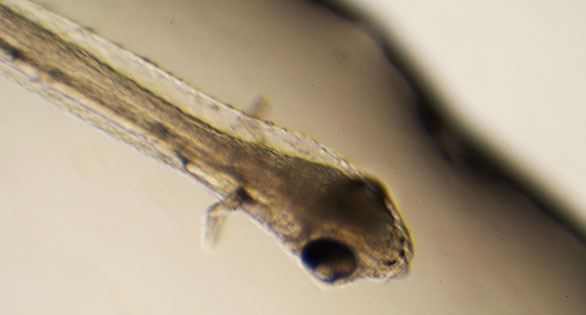

By day 20 the larval parrotfish were still very small, but seemed to spend most of their time right at the surface, often striking at food but otherwise sitting very still in the water. Their coloration was quite amazing. The rear half of their green eyes were red. Around this time we added two sizes of copepods, making sure they were egg-bearing. We kept the densities high and changed the water frequently. This is obviously difficult because the fry are so small and sensitive; we have to do it slowly and continuously.

There are a few culture techniques that I am not able to share until:

a) I have shown that they contributed to the success of this culture, and

b) I have published them in a scientific journal.

I will say that these practices are all commonplace; it was just the unique combination of factors that seemed to get the larvae through the first week.

On day 37 the parrotfish finally dropped out of the water column and clung to the tank’s walls. The newly settled Bumphead Parrotfish juveniles clustered around any algae or feature in the tank, so we added a few pieces of live rock to provide additional substrate features. They were colored brown with black spots and remained very still on the bottom. By day 47 they began schooling in groups of 10–25, literally cruising around the tank continuously all day. This inspired us to add more live rock, which seemed to be what they were looking for—habitat. They used this rock for bedding down at night, but continued to school during the day, going around and around the tank.

Now, at day 155, we have about 130 Bumpheads weaning onto pellet feed. I plan to start adding calcium to the feed and conduct trials to monitor their growth.

Why raise Bumpheads?

Most people would guess that the main reason for culturing Bumpheads is their value as food on the international market. This is partly true (especially in the private sector), but for me the main goal is to start a restocking program in which they are raised to a size large enough for reintroduction to the waters of the Pacific islands where they once thrived. With proper marine protection (which is actually a reality today), these fish could repopulate, which could lead to a sustainable fishery if they are managed correctly. They are long-lived (40 years or more) and produce many eggs every month, so they have high “rebound” potential. Another factor that might increase their survivability is that, unfortunately, most island nations in the Pacific have few, if any, remaining large predatory sharks—one of the Bumphead’s main natural predators. This may actually give them a head start on the road to repopulation, although there is no scientific evidence to support this.

To my surprise, the Bumpheads seem to be excellent aquarium companions. They are feeding on a mix of live feed and pellets. They display very unusual and appealing coloration, and they seem to blend into a community tank quite well. I particularly like their personality, which is characterized by a quiet confidence. The juveniles are not aggressive, but they will stand up to tankmates and swim about in their unusual parrotfish way as though they are gliding, not swimming. I find they remind me of seahorse juveniles; when you first approach the tank they will turn their backs and watch you with one eye until they get used to you.

There are many reliable spawning aggregations throughout the world, and this is clearly the most affordable and efficient form of gamete collection for difficult-to-breed captive fish species. Variables such as weather, tides, and overfishing obviously make things slightly unpredictable, but there is also a great amount of uncertainty when conditioning and spawning broodstock fish in captivity.

In Closing

The Bumphead Parrotfish is an icon. This peaceful giant represents ocean health, vibrant reefs, and food security. The reefs may never again be as healthy as they once were; for various reasons, many reef species are dying, so now is the time to act. Along with other conservation practices, we know how to protect the healthy reefs that remain and are learning how to repopulate those that are barren. The science is in, and it shows that sustainable, efficient fishing practices can yield excellent results. Reefs can remain protected and still act as larval nurseries for nearby areas. In fact, recent studies in Australia have proved that not only does fishing a smaller area result in a higher yield, but the fish that are caught are also consistently bigger. This same principal is used for sustainable aquarium collecting…because it works.

About the Author

Tom Bowling is a marine biologist with a degree from James Cook University, Australia and a former commercial diver.

Credits

Underwater images: Richard Barnden/Biota Aquaculture

Tom Bowling author photograph: Tatiana Bowling

Connections

Sam’s Tours Palau

Like what you read? Don’t miss the forthcoming May/June issue of CORAL Magazine, and be sure to tell your friends!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks