A Blue Starfish (Linckia laevigata) resting on hard Acropora coral. Lighthouse, Ribbon Reefs, Great Barrier Reef. Image: Richard Ling/CC. Click to enlarge.

Readers of this blog may justifiably exclaim, “OMG!!! – Shimek is posting about a coral reef animal!!! Yikes and Gadzooks, the world may end!!!”

Well, not only am I writing about a coral reef animal, but it is also about a common, well-known, and amongst some folks, a favorite animal of sorts, the Blue Reef Starfish, Linckia laevigata. The only amphipod in the paella is that the Blue Reef Sea Star is an animal I have counseled most hobbyists for many years not to purchase as its reef-tank survival is quite difficult to ensure.

This blog post, though, is really is more about sea stars in general than it is about Linckia laevigata. Or, at least, I can claim that is the fact, even if virtually all of the interesting stuff is specifically about the Blue Linckia Sea Star.

A Cold Case

One of the more popular genres of broadcasting whodunits is the “cold case”, where the good guys, gals, aliens, or computers, are trying to solve a crime that may be several years to a few decades to centuries old. Recently, I watched one such program where not only was the crime case “cold,” the victim lived about 5,400 years ago; the victim was also cold; very cold, having been discovered frozen in an Alpine ice field. Given name Ötzi for the locality where he was found, he remains frozen in a research facility. Good forensic science is good science, and I found the program investigating the cause of his death to be quite enjoyable.

A peculiarity of “old” or “cold” invertebrate zoology questions is that they may be one of two types. The first type is a question that relates to some sort of evolutionary phenomenon. In this case, the event or events being discussed might be millions of years old, even if the question was first asked this morning. The second type is a question that was initially asked a long time ago regardless of when the events it concerns take place. In these latter cases, the questions themselves may or may not concern some process that occurred in the distant past, but the question itself may be decades to centuries old.

The Sea Star/Linckia laevigata Question

Early in the study of echinoderms, in general, and sea stars in particular, it was noticed that these animals were really peculiar. First off, their anatomy is acraniate, where “a” means without and “cranium” is a head, so perhaps all echinoderms may be favorites of Ichabod Crane, and perhaps Washington Irving could have given the character in his story the more fitting name of Ichabod Acranium, as he was destined to boogie the Halloween hop leading to the encounter with one of the most enduring headliners of all times, the headless horseman.

As might be expected, without a head, echinoderms are missing most structures normally found in that body region, and questions about alterations in their behavior and physiology resulting from such lacks have been continuously posed. However, echinoderms are so bizarre in all aspects of their anatomy that lacking such normally important structures as the head, eyes, or brain almost seem normal, and such questions fell into place with the hope that someday they might be answerable.

It should be noted that quite a few other animal groups have also evolutionarily lost their heads, or portions thereof. Primarily notable, in this regard, are the clams, congress critters, brachiopods, and peanut worms. It appears, in most cases, that immobile animals don’t need heads, and they also don’t have much in the way of brains. If you are stuck in one spot and can’t do much to get away from a predator, all the brains in the world are not going to help when push comes to shove.

However, sea stars move, some at quite a respectable rate. Generally, animals that move have eyes, and those eyes are right up front. Presumably this is so that the critter can find out where it is going, and what it will bump into or perhaps more importantly, what is waiting up ahead to eat it? But with sea stars… what is the front?

The stars can and do move in any direction, but no particular structure or arm is “the front”. So, no head, no brain, and no front end. However, it has been known for many years that sea stars have some sort of photoreceptive devices, called eye spots, found at the tips of each ray, but nobody has had a clue what they were used for or any data on how they were used.

Until now…

Researchers looking at the common blue reef star, Linckia laevigata, examined the photoreceptors found on the tips of each arm that they found on a specimen purchased at a Copenhagen aquarium store. Sea star eyes typically are situated at the tip of each arm, and they point downward, so to see anything but a close up view of sand or rock, the arm tip has to bend up roughly 90 degrees. The eye is comprised of about 150 to 200 units called ommatidia, with about 100 to 150 photoreceptor cells each.

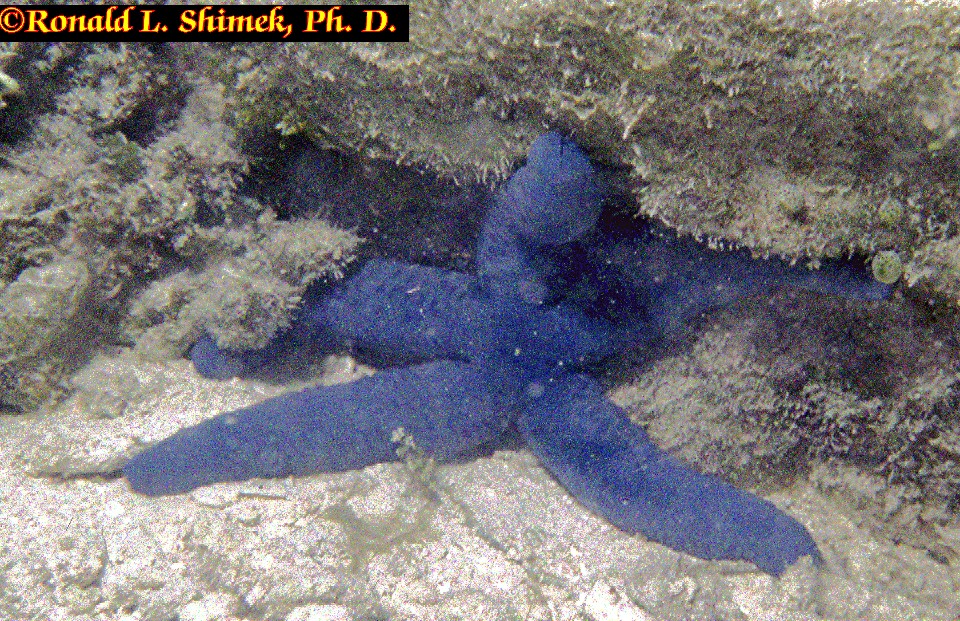

A Linckia laevigata in Belau, 1991.

Like other starfish species, L. laevigata’s eyes can form images, but the resolution is very low, really about all they can see is large masses of dark or light. The neat part is that the eyes are in a groove that is lined with black pigmented tissue, which has the effect of creating a directional slit for light to approach the eye. Without a brain, it is really unclear how the image created by the eye is used, however, if the arm is extended the eye could tell the difference between a large dark object (a reef) and a large light colored object (a sand flat).

The researchers went to a reef in the field and performed operations surgically removing the eyes from some Linckia stars, or, as a control, surgically removing some tube feet from another group. After the surgery, the stars were allowed to heal overnight. They next day they were placed on the sand near the reef. The stars with the mock operations all moved toward and then on to the reef, while none of the eyeless stars moved toward the reef.

At least in this one situation, it appears that the photoreceptors of Linckia laevigata sea star individuals can help them find their way home. I suspect the same situation may hold true for Linckia multifora. As for other stars… experiments await.