Is This The Beginning Of The Collapse Of Another Echinoderm-Structured Biome?

The time line:

1962-1963. Washington State.

After a young professor at the University of Washington spent some time casting around for a research project he would find interesting, he became interested in the exposed outer coast near Cape Flattery, the most northwest point of the continental United States.

After examining the rocky intertidal community on the exposed coast, he decided to investigate the role played by Pisaster ochraceus, a common intertidal sea star, in structuring that community.

The two most common color morphs of Pisaster ochraceus are orange/ochre and purple

The scientist, Dr. Robert T. Paine, decided the easiest way to ascertain what the sea star was doing was to remove it. He started several experimental sites, initially on the mainland, but eventually most of his work was done on Tatoosh Island, at the tip of the Cape. He visited these sites during every low tide during what would be most of the rest of his life. When on these sites, he picked up and threw into deep water, or otherwise removed, every P. ochraceus individual he could find. On control sites, he picked up and manipulated the stars but then put them back on the site. In a very short time the Pisaster ochraceus population was almost nonexistent on the experimental sites, but the control sites looked to be normal.

1964-1965.

Within a couple of years, the sites lacking sea stars showed tremendous changes. Both barnacles and muscles settled on the sites in huge numbers. Both grew at tremendous rates and soon were much larger and in much denser populations than on the control sites. Over time the mussels grew much larger than normal and moved down in the intertidal zone displacing and removing the barnacles. Likewise the subtidal kelp began to move upward into the intertidal zone. After a while the rocky intertidal community which had been a diverse array of several zones or layers of algae, two types of mussels and about a half dozen types of barnacles, as well as numerous anemones, and other fauna such as crabs, snails, and worms, had “collapsed” into a dense upper layer that consisted primarily of one mussel species, Mytilus californianus, and a dense lower region consisting of a couple of species of small kelps. Virtually all of the evident diversity found in this region “disappeared”.

See: Paine, R. 1966. Food Web Complexity and Species Diversity. American Naturalist. Available online at http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/282400

From 1966 until a couple of years ago.

This low diversity intertidal zone was maintained by the removal of the sea stars. When the stars were allowed to return, over the course of a few years or so, the normal intertidal array was re-established. Paine, his colleagues, and students explored many aspects of this system.

1969.

The concept of a keystone species was published and Pisaster ochraceus was designated as a keystone species. It was the first species so designated and it was Dr. Paine’s brilliant work that showed how the whole system worked.

See: Paine, R. 1969. A Note on Trophic Complexity and Community Stability. American Naturalist. Available online at http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/282586.

In many marine communities, it was found that echinoderms are often keystone species.

1983. The Caribbean Basin

A disease starts killing the long-spined sea urchins around Belize.

1984.

The long-spined sea urchins are being killing all around the Caribbean.

1985.

The panzooic burns itself out having essentially wiped out the huge populations of Diadema antillarum found in the Caribbean, although some small residual populations remain.

As a result of the loss of the grazing by Diadema, algae overgrow coral reefs and the reefs change from coral reefs to mixed sponge algal reefs. Some remnant coral areas remain but the character of the reef has been drastically changed.

Diadema antillarium is belatedly recognized to have been a keystone species.

2013 October and November. Oregon.

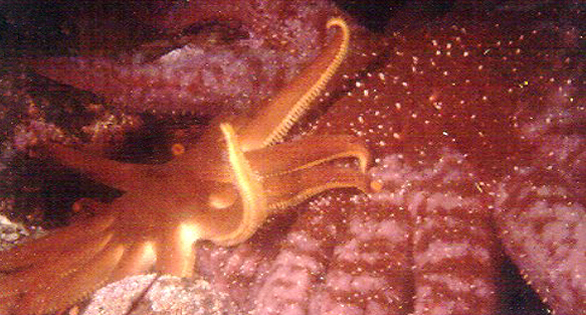

A Solaster dawsoni, about 30 cm in diameter, is attacking a Pycnopodia helianthoides about three times its size. Both of these species have been seen dying in huge numbers in October and November, 2013.

Reports of sea star populations where the animals are “dying by the thousands.”

There are several videos making the rounds:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jGfYLdOQQ0c

(also see the article about this video)

“See all that white stuff on the bottom?? Those are decaying, white tissues and ossicles from sunflower stars. You can see the fleshy remains all around the bottoms.”

Already known from studies in the late 20th Century as likely keystone predators, such mortality foreshadows tremendous changes in the shallow subtidal Oregon biome, which…

Is arguably the richest temperate marine region in the world.

Or

Was arguably was the richest temperate marine region in the world.

It certainly appears that once more, echinoderm keystones are being removed from the ecological arches…

These dramatic images and videos will play themselves out over the next year or three. However, if they are representative, and such mortality is widespread, it is likely the Pacific Coast marine environment will change for the worse.

we all need to wake up our common sense and do whatever it takes to help this situation, before it is humans washing up somewhere….it’s frightening!

Here’s a very informative blog called the Marine Detective, investigating this same story:

http://themarinedetective.com/2013/11/10/wasted-what-is-happening-to-the-sea-stars-of-the-ne-pacific/

Hi,

Getting my information. For the Paine portion = I was a grad student at the U. Wash. during some of this work. Lotsa talking, helping on field trips, and reading his papers gave me all the information I needed for that story. I still have some friends there who keep me informed of what is happening in that region.

With regard to the other stuff, information came from published peer-reviewed research articles.

Basically for anybody now to get good info, you need to search the net for papers. I have given links to a couple of papers that should give a start. Then, to get more search on these termsa; Robert T. Paine (and use the variants of the name = R. T. Paine, R. Treat Paine, etc), Keystone Species, Robert Vadas, Bruce Menge, Pisaster ochraceus, etc. Doing a search on those names on Google, and especially Google Scholar will get a lot hits. Oh yeah, doing a search on my name will be a waste of your time for this topic, my own research was on a vastly different topic.

Happy Trails,

Ron Shimek

“EXCELLENT, THANK YOU ! Another tip, if you don’t see Lifeframe in all programs (because mine didn’t) just type it in and it will come up on the top in a box that doesn’t look like it’s clickable, but click it. Once it opened, I right clicked the icon and pinned it to my task bar so I don’t have to hunt it down any more.

“