Young Ambon Damselfish on the reef, small and extremely vulnerable to predation. Image: Oona Lonnstadt.

The old proverb about a leopard not being able to change its spots now has a new biological footnote after researchers in Australian recently found that fish exposed to predatory danger can, indeed, transform their spots to make them less vulnerable to attack.

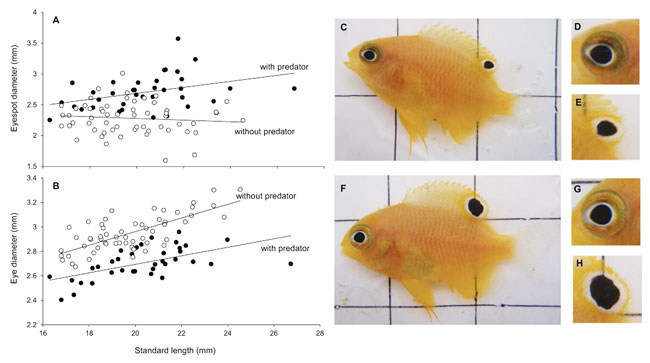

Working with young Ambon Damselfish, Pomacentrus amboinensis, researchers from Australia’s ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies (CoECRS) have made the remarkable discovery that, when constantly threatened with being eaten, the fish not only grow a larger false ‘eyespot’ near their tail–but also reduce the size of their real eyes. Small prey fish with bigger “false eyes” on their rear fins dramatically boosted their chances of survival on the reef, they found.

Relationships between eyespot size and eyeball size and body length. The relationship between standard length and eyespot diameter (A) and standard length and eye diameter (B) in presence and absence of predators. All prey fish exposed to predator cues over a 6 week period had significantly larger eyespots (F,H) and smaller eyes (F,G) than fish from the control treatments (C–E).

The changes were not evolutionary—over a succession of generations—but rather a relatively rapid response by individual fish tracked over a period of six weeks.

The enlargement of the eyespots results in a fish that looks like it is heading in the opposite direction–potentially confusing predatory fish targeting them to be eaten, says Oona Lönnstedt, working toward her Ph.D. at CoECRS and James Cook University.

These spots are known as ocelli, and for decades scientists have debated whether false eyespots, or dark circular marks on less vulnerable regions of the bodies of prey animals, played an important role in protecting them from predators–or were simply a fortuitous evolutionary accident. The widely accepted theory is that these spots, found in the juveniles of many species, tend to cause predators to strike at the eyespotted tail or fin rather than the much more vulnerable head region.

The CoECRS team has found the first clear evidence that fish can change the size of both the misleading spot and their real eye to maximise their chances of survival when under threat.

“It’s an amazing feat of cunning for a tiny fish,” Lonnstedt says. “Young damsel fish are pale yellow in colour and have this distinctive black circular ‘eye’ marking towards their tail, which fades as they mature. We figured it must serve an important purpose when they are young.”

“We found that when young damsel fish were placed in a specially built tank where they could see and smell predatory fish without being attacked, they automatically began to grow a bigger eye spot, and their real eye became relatively smaller, compared with damsels exposed only to herbivorous fish, or isolated ones.

“We believe this is the first study to document predator-induced changes in the size of eyes and eye-spots in prey animals.”

When the researchers investigated what happens in nature on a coral reef with lots of predators, they found that juvenile damsel fish with enlarged eye spots had an amazing five-fold increase in survival rate compared to fish with a normal-sized spot.

“This was dramatic proof that eyespots work—and give young fish a hugely increased chance of not being eaten,” says Lonnstedt.

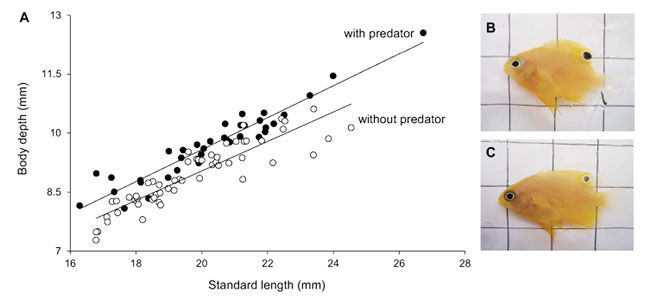

Comparison of depth to length ratio. The relationship between standard length (SL) and body depth (BD) of P. amboinensis when in the presence and absence of predators (A). Fish had significantly deeper bodies when exposed to predator cues (B) compared to the shallow bodied controls (C).

“We think the eyespots not only cause the predator to attack the wrong end of the fish, enabling it to escape by accelerating in the opposite direction, but also reduce the risk of fatal injury to the head,” she explains.

The team also noted that when placed in proximity to a predator the young damsel fish also adopted other protective behaviours and features, including reducing activity levels, taking refuge more often and developing a chunkier body shape less easy for a predator to swallow.

“It all goes to show that even a very young, tiny fish a few millimetres long have evolved quite a range of clever strategies for survival which they can deploy when a threatening situation demands,” Ms Lonnstedt says.

Their paper Predator-induced changes in the growth of eyes and false eyespots by Oona M. Lonnstedt, Mark I. McCormick and Douglas P. Chivers appears in the latest issue of the journal Scientific Reports.

ABSTRACT

The animal world is full of brilliant colours and striking patterns that serve to hide individuals or attract the attention of others. False eyespots are pervasive across a variety of animal taxa and are among natures most conspicuous markings. Understanding the adaptive significance of eyespots has long fascinated evolutionary ecologists. Here we show for the first time that the size of eyespots is plastic and increases upon exposure to predators. Associated with the growth of eyespots there is a corresponding reduction in growth of eyes in juvenile Ambon damselfish,Pomacentrus amboinensis. These morphological changes likely direct attacks away from the head region. Exposure to predators also induced changes in prey behaviour and morphology. Such changes could prevent or deter attacks and increase burst speed, aiding in escape. Damselfish exposed to predators had drastically higher survival suffering only 10% mortality while controls suffered 60% mortality 72 h after release.

Sources

From materials released by the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies (CoECRS).

http://www.coralcoe.org.au/

Featured Image credit: http://www.ibrc-bali.org/research/project/pomacentrus-amboinensis/

Indonesian Biodiversity Research Center

Images this page: Oona Lonnstadt, top.