Excerpt from CORAL, September/October 2012

article by Dick Perrin; images by Bryan Meldau

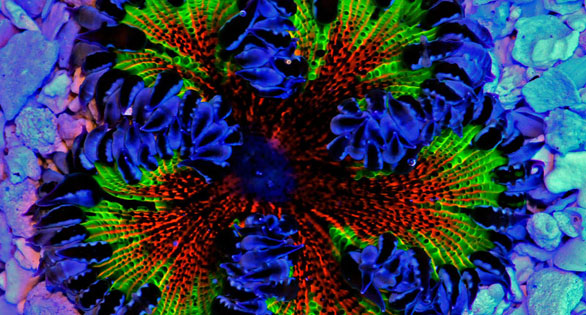

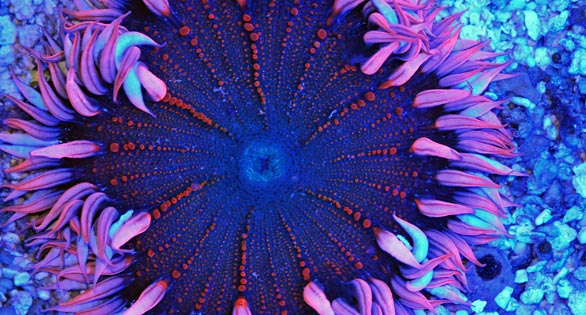

More than 50 years ago, when I began exploring the shallow waters of the Florida Keys, I was amazed by the variety and abundance of life in the rocky areas and grass flats. Many of the turtle grass meadows had good numbers of anemones, such as Florida Pink Tips (Condylactis gigantea) and Rock Anemones (Epicystis crucifer), also known as Flower or Beaded Anemones. The pinks and purples and the larger sizes made the condys the more desirable choice for home aquarists. Most of the Rock Anemones had little color, although occasionally you would find a good green, and, much more rarely, a red one. Florida sunshine and typical aquarium lighting did little justice to these “Red Rocks,” and it wasn’t until the arrival of blue lighting for reef tanks, especially the recent surge in the use of blue LEDs, that the amazing beauty of these red-pigmented Epicystis crucifers was finally revealed.

Dick Perrin with Rock Anemone raceway at his Tropicorium aquaculture facility near Detroit, Michigan.

Their smaller size—usually 3 to 4 inches (7.6–10 cm) maximum—and the likelihood that they will stay pretty much where you put them, plus a weaker sting than almost all other anemones, makes Red Rocks an excellent candidate for most aquariums. Like most aquarium-suitable anemones, they harbor populations of symbiotic photosynthetic zooxanthellae, which go a long way toward keeping the anemones nourished when supplied with the proper moderate to moderately bright lighting, similar to that required for soft coral culture (or a little brighter).

Keeping a growing population of these animals in our greenhouse aquaculture facility in Michigan (where the staff calls them “Rock ’Nems”), we have found it beneficial to supplement their diet with some meaty food two or three times a week. Small pieces of table shrimp, Mysis shrimp or marine fish work well, ideally about a quarter-teaspoon per adult per feeding. If you want to breed them, more frequent feedings are appropriate.

Hidden “Wow!” Factor

Whenever one of these incredibly rare Red Rocks is exhibited under blue lights at my facility, customer interest soars off the charts. There are a lot of “ooohs” and “aaahs,” and no one seems immune to their beauty, but their scarcity has made it exceedingly difficult for many to have them.

An accidental rock anemone reproduction event some years ago, when about 20 small ones showed up in a tray with an adult, convinced me that there was a possible opportunity for captive culture. There were two unknowns: could we predictably reproduce Epicystis crucifer, and, more important, would the offspring have the colors of the adults? The abundance of and low demand for the common brown and tan color morphs make any efforts to reproduce them commercially unappealing.

Once we had made the decision to move ahead with this venture, the daunting task of obtaining a sufficient number of Red Rock Anemones to establish a breeding colony seemed an insurmountable goal. To add to the problem, there turned out to be many color and pattern types of the Red Rock Anemone, some much more desirable than others, and we wanted to breed the most beautiful and interesting patterns.

As a saltwater shop owner since 1959, and having established the first coral farm in the world on the outskirts of Detroit, I had dealt with and gotten to know many Florida collectors. I called in favors as best I could, and some of the collectors went hunting for my breeding stock; I went down to the Keys myself several times to help out. We finally amassed what I considered a workable number, and, as no one could resist collecting the outstanding green ones, they became part of my breeding colony, too.

Inland Aquafarm

Tropicorium is a coral farm and saltwater shop of more than 50,000 gallons (189,271 L), consisting of eight 7 x 16-foot (2.1 x 4.8-m) vats, eight 6 x 6-foot (1.8 x 4.8-m) vats, and over 100 glass tanks, all in three large, energy-efficient greenhouses. The vats are between 24 and 32 inches (61–81 cm) deep. Most of them are “rollover” tanks, each with a fiberglass table about 8 inches (20 cm) below the water surface and extending wall to wall but missing either end by about 11 inches (28 cm). Each “rollover” vat has 15 1.5-inch (3.8-cm) diameter elbow pipes with 15-inch (38-cm) rigid air lines injecting air down the pipe and speeding the aerated water through the 10-inch (25-cm), half-submerged horizontal portion of the elbow lengthwise over the table, assisted by one or two power heads. This entire concept of water circulation is unique to us. The water “falls” down through the 11-inch open end and flows under the table, passing about a ton of live rock and about 5 inches (13 cm) of gravel, and then up and over again—hence the name “rollover.” In addition to the daylight penetrating the greenhouse panels, we have three to five 400-watt metal halide 20,000K lamps over most of the vats.

One of the 6 x 16-foot vats was chosen as the breeding tank, as the health level of the animals in that vat was exceptionally high. Rectangular plastic trays about 9 x 13 x 3 inches (23 x 33 x 7.5 cm) deep were filled with a layer of small rock first, then topped up with CaribSea FCC (Florida Crushed Coral, their product name for a 2–4-mm grit size aragonitic material), the same material that is used on the bottoms of the vats. The anemones were placed in depressions in the gravel at about eight to twelve per tray, depending on the size of the anemones. The anemones opened up to about 2 to 3 inches (5–7.5 cm) across within a day or two.

We felt a diet heavy on protein would work the best, so we offered them chopped table shrimp, Mysis shrimp, Cyclop-Eeze, fish, and multivitamins, which we fed to one side of the anemones’ perimeter tentacles every day with a turkey baster. The food stuck very well to the tentacles, and they quickly folded it over to their mouths. Within two to three weeks, most had added nearly half an inch to their diameter, although their growth rate was much slower after this point.

First Babies

It was about six weeks into the daily feeding regimen when we first noticed several babies partially under one of the adults. They were very tiny, about 4 mm from tip to tip across the tentacles, of which there were six or seven. In the next few days, five or six more showed up, after which they began to show up even more frequently. We lifted them out, along with the several grains of gravel they were attached to, and placed them in a deeper gravel-bottomed tray. We found that after feeding the adults, they would partially retract, exposing the babies.

The tray holding the babies was lifted from the vat daily and brine shrimp nauplii or CYCLOP-EEZE were added to the tray and swirled around. After an hour or so, the tray was returned to the vat. Over the next month, we recovered more than 300 babies, and they occupied two additional trays. At this point, the oldest babies were six or seven weeks old; up until five weeks, the babies hadn’t shown any real color. It was pretty discouraging. But shortly after the fifth week, when the largest babies were about half an inch across, several turned red. Over the next week or so, six to eight more turned red or green. Although we tried to make sure that all the babies were fed properly, it became evident that there would be much variation in individual growth rates. At this point, mid-October in our cold northern state, the shorter days caused a total stoppage of babies being produced. We tried extending the photoperiod with the metal halides and warming the water, which helped a little, but we only got a few additional babies.

The babies we did have, however, continued to grow, and more and more of them began coloring up. Now, more than half of them were red or green, and many showed the amazing coloring and patterning of the adults. But, surprisingly, some showed new patterns and colors unlike those of any of the adults and were even more attractive.

Sexual Reproduction

All along, we had suspected that the reproductive method would be pedal laceration, in which a portion of the sloughed-off pedal tissue from the parent would grow into a clone of the parent. The difference in appearance of some of the young from that of the parents suggests sexual reproduction as opposed to cloning. Julian Sprung reports (The Reef Aquarium, Volume 2) seeing sperm release from male Epicystis, which we have also seen here. The sperm release event we observed lasted six to eight minutes and did not trigger other breeding activity in the surrounding Epicystis, as often happens with Tridacna clams. Sprung further reports observing reproductive material (eggs or larvae) being released from the tentacles of Epicystis. In early March 2012, we observed several young partially under a tentacle of a green Epicystis. Upon moving other tentacles, we observed nearly 40 babies, evenly distributed around the base and under the tentacles. A day or so later, these babies had “clumped” into three bunches.

This series of events and observations led us to conclude that Epicystis is a dioecious species (separate males and females) and that the females had taken in the broadcast sperm for internal fertilization and “brooded” the offspring for later release as larvae. The early, even distribution of young suggests that the larvae make their way through the tentacles or the base of the mother and migrate out under the protection of the tentacles, as opposed to being released through the oral opening, where the even distribution of young would be much less likely and the chance of observing a baby traveling across the disc of the mother is very high. The fact that almost all the babies were recovered from under the tentacles of the adults further supports tentacle distribution of young.

The March 2012 breeding event that yielded nearly 40 babies was very different from all previous breeding events. The number of babies was unprecedented, and they were more than twice the size of the earlier ones and had more than twice the number of tentacles. For the first time, the babies were fully colored like the parent, bright green. This parent had been in captivity in warm water for seven or eight months, and had been heavily fed on a daily basis over this period; it was also one of the larger specimens originally collected, and had grown beyond that to over 4 inches (10 cm). We feel this combination of factors led to this prolific breeding event.

As winter gave way to spring, most of the adults had grown to 4 inches or more and many had intensified in color, becoming even more attractive. The babies continued to color up and grow. More than 90 percent had turned an attractive color—mostly reds and greens, some oranges (unlike any of the parents), and a variety of other color mixes and patterns.

At this point, many of the young have reached a disc diameter of 1.5 inches (3.8 cm) or a little more. Despite offers and pleadings, we have not sold any of them yet. We wish to retain the most interesting specimens for additional breeding stock. There seems to be little doubt that the reason we produced 300 and not 3,000 offspring is the late start of the breeding effort and the many immature breeders involved. We have learned in discussions with some Florida collectors that there appear to be both spring and fall reproductive seasons, when many small anemones appear around the adults. That would coincide with the breeding event here in the fall and its end shortly after.

We are looking forward to a better harvest this fall, because we have many well-fed full adults. Plus, a new collector has discovered some color morphs of a smaller variety that are very attractive and quite different from the previous ones, and we are hoping for offspring from these new ones, too. We will attempt to extend the fall breeding period with an extended photoperiod and hope to produce enough that, eventually, they will be available to everyone.

Dick Perrin has been a saltwater shop owner, steelworker, residential designer and builder, coral farm owner, lecturer for the reef hobby, and NASA halophyte biofuel researcher and developer. He is the owner and operator of Tropicorium, in Romulus, Michigan, which was the first, and is still one of the largest, coral propagation facilities in the United States.

References:

Delbeek, Charles J. and Sprung, Julian. The Reef Aquarium, Vol. 2. Ricordea Publishing, Coconut Grove, Florida, 386–7.

Fossa, Svain A. and Nilsen, Alf Jacob. The Modern Coral Reef Aquarium, Vol. 2. Birgit Schmettkamp Verlag, Germany, 259–60.

on the Internet:

http://www.tropicorium.com

The ugly duckling… Arrival seems to end mid sentence. Is it just me? I was into the article and boom it ended just like that.

Eric,

Thanks for the heads up. Article is now fixed.

http://www.reef2rainforest.com/2012/08/27/ugly-duckling-anemones-in-a-new-light/

James